The first time I cooked one of those new-generation fake-meat plant-burgers, I went the whole hog. I bought an excellent bun and some Japanese pickles. I dressed a salad and made two separate sauces. But you know what? I ended up eating a (very nice) salad sandwich. The fake-meat wasn’t quite right, and – hating it for that – I took it out of the bun, and out of my sight and smell.

Things have been getting better. In 2019, tasters carrying out an ‘imitation burger’ ranking for the website Serious Eats asked whether the Impossible Burger – sold at Burger King – was ‘in fact, a real burger thrown in the mix’. And in a taste test last year in The Guardian, a vegan chef described the Beyond Meat Beyond Burger as his winner: ‘It boasts a juicy and convincingly meaty texture, with a brilliantly beefy flavour and a moreish pink centre.’ After an initial strong increase in demand, further growth is being held back by the relatively high costs of plant-based meat. In 2022, Deloitte reported that, ‘after years of double-digit growth, sales are now flat’. But for those of us seeking properly realistic alternatives, progress is undeniable.

Most promising is the phenomenon of lab-grown meat. Currently, it’s approved for sale only in Singapore. But a US brand of lab-grown chicken was recently designated safe for human consumption by the US Food and Drug Administration. And Ivy Farm, a spin-out of the University of Oxford that aims to produce more than 6,000 lbs of cultivated meat a year, recently opened the largest pilot manufacturing plant in Europe.

This is the future I’ve been dreaming of. For years, I’ve been telling myself that it’s the lab-grown-meat-makers who’ll finally stop my base desires from making a mockery of my higher-order wish to be morally good. Because I’m pretty convinced that eating dead animals is bad, yet I do it a lot. Until recently, I’d never even tried to cut down.

Sure, I do it as ‘ethically’ as I can: buying free-range, reading regulations, asking about provenance, spending more and more in the hope of the highest welfare standards. Ultimately, however, my concern isn’t with lax welfare. Not because I don’t think that’s a serious concern: of course it is. But because, even if that particular problem were solved, and all the animals served up had had the best possible lives and deaths, I’d still think eating their meat was wrong.

This hinges on my sense that eating dead animals represents a failure of moral respect. That the wrong I do by eating them isn’t reducible to how they were treated while living and dying. And that this is a wrong that occurs even though the animals themselves, by definition, aren’t here to experience it.

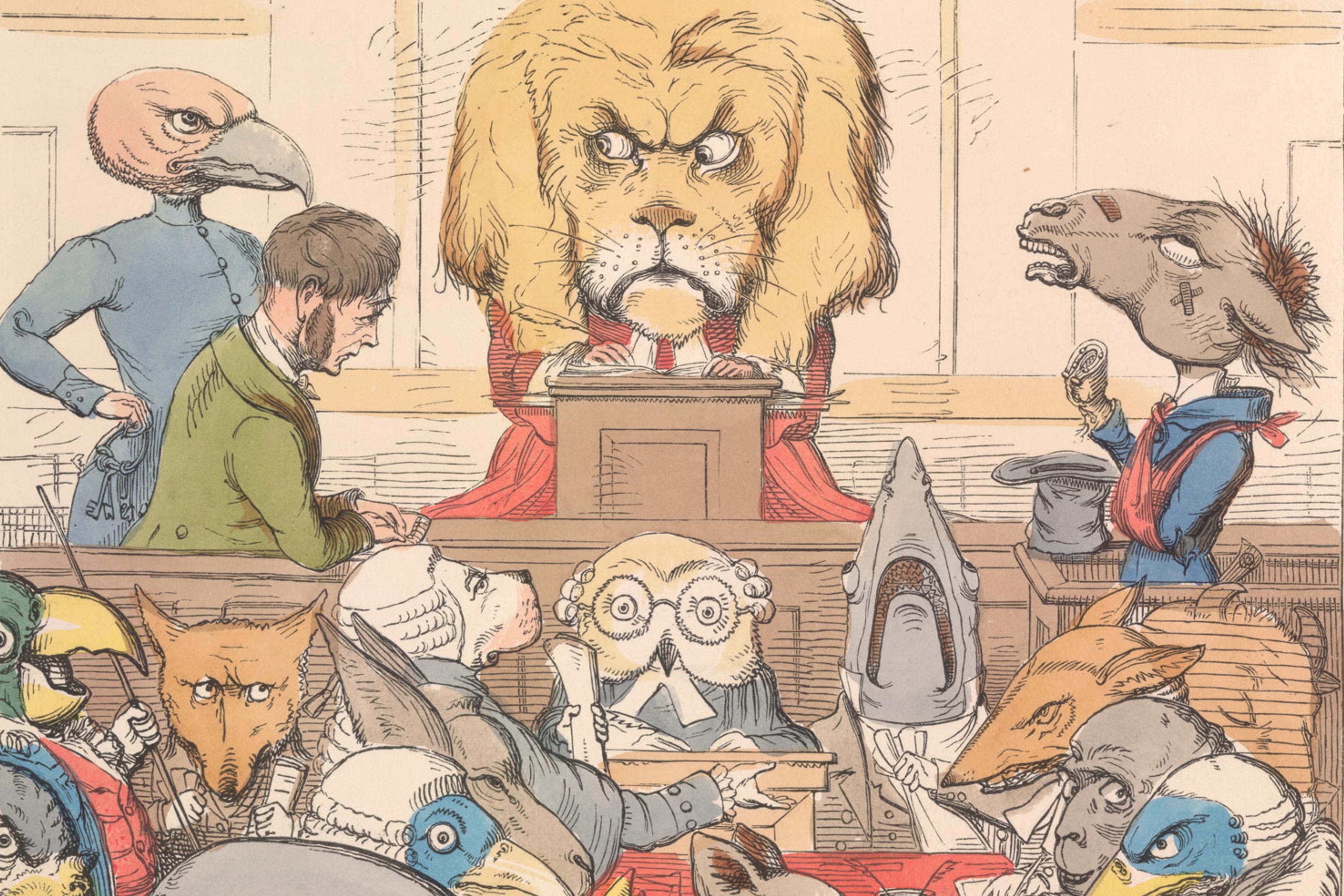

It’s a failure of the same kind of respect, therefore, that most of us instinctively feel we owe to the bodies of dead humans. It’s why you’d feel uncomfortable dancing on a grave, or playing games with the bones of skeletons. It’s why I hate museum exhibitions displaying bodies, and especially those glamorising or making jokes about them. Fundamentally, it comes down to the obligations that we humans – as moral beings – owe to other living things. Obligations, minimally, to behave towards them as beings who share our interest in living, beings whom we shouldn’t treat cavalierly, beings whom we shouldn’t unthinkingly exploit or instrumentalise.

I get this might seem extreme. You might tell me that eating dead animals isn’t comparable to playing games with them; that we need to eat to live. And that, if we have obligations of respect to the animals we eat simply because they’re the kind of thing that lives, then we’ll have to seriously rethink our interactions with fleas and flowers. Well, we probably should rethink some of those interactions. But I’m not suggesting all these obligations are equal.

So let’s say I’m particularly concerned about showing sufficient respect to the animals who participate in our society, especially those we’ve domesticated. And let’s agree that, while eating is more crucial to human life than playing games, most of us can choose to subsist comfortably by eating non-meat products. And that eating an animal’s meat – particularly when done for pleasure, rather than need – degrades its moral status. That doing so is to say: this is the type of living thing, unlike the human being, whose dead body we can treat in this way. Whose dead body we can touch, taste, subsume, destroy – for our pleasure.

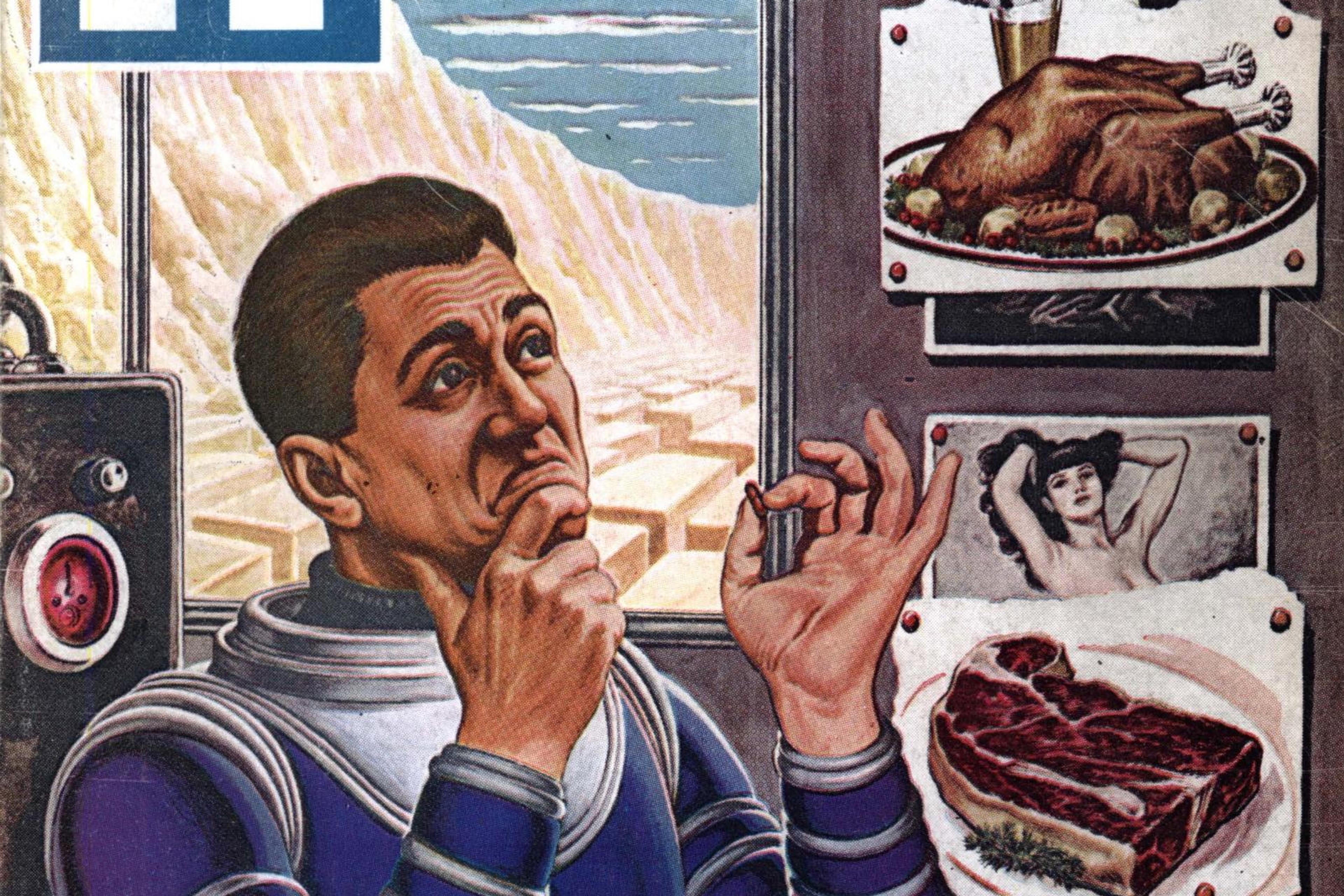

I’ll admit now that my inability – no, my unwillingness – to stop eating meat has often convinced me that I’m a bad person. What else would I do, believing it wrong, just for an enjoyable sensation? I’ve reasoned my way out of this, sometimes. I’ve accepted that, to me, eating meat is more than any old enjoyable sensation. This’ll sound sad, but eating (and cooking) meat is one of the greatest pleasures of my life. More relevantly, though, somewhere underneath, I probably hold one of those mitigating naturalistic-type beliefs: that really, it’s permissible to eat meat, even when we don’t need to, because it’s in our nature. We’re carnivores! Sure, there’s pea protein. And sure, lots of things that are ‘natural’ for us to do aren’t good in themselves. But we’ve got to be able to square this.

Even if we could square it, I want to believe it’s wrong to eat meat. I want to accept that it’s insufficiently respectful to the creatures around us. That I’d be living in better accordance with the good, if I just stopped. And that this pertains to something simpler and deeper than the classic question of which ‘second-order’ issues drive and distinguish our moral requirements, here: whether, like Peter Singer, you think we should focus on the animals’ sentience; or, like Martha Nussbaum, on their potential to flourish.

Bring on the easily accessible, top-quality lab-grown meat. The exact same meat fix – the taste, texture, cooking complexities – without needing to eat the animals we live alongside. Good times! Or so I thought, until the other week.

Mr X’s behaviour towards the woman-replicant represents a failure of respect towards womankind

I saw a Tweet celebrating the latest fake-meat burger. As usual, I also saw unnecessarily angry replies, shouting: ‘Why don’t they just eat vegetables?!’ Previously, I’d found such comments annoyingly simplistic; this idea that, if you don’t want to eat meat, then why seek to replicate it? Such an idea seemed to miss the basic point: that many people who don’t want to eat meat nonetheless think it has unique qualities worth replicating – not least the great taste. But then I realised I’d been missing a deeper point. A point that potentially wrecked my hopes for depending on lab technicians as moral saviours.

It comes down to the following problem. If my overriding fundamental concern with eating meat isn’t lax welfare – or other (conceivably, eventually) fixable matters, like the environmental damage caused by intensive farming – or anything except the failure of respect discussed above, then why would eating a replicant suffice? I mean, wouldn’t there be something deeply wrong about eating a replicant human steak? And wouldn’t it hinge on something much more than disgust, or the fear of demand stimulation?

A useful analogy is the bad treatment of sex dolls. Imagine Mr X doing something to a woman-replicant doll that would be (whatever it was) undeniably degrading if done to an actual woman. Now, I don’t need to argue that such behaviour should be illegal – though there’s a strong case for outlawing the sale of, particularly, child-replicant sex dolls. Instead, I’m suggesting that there’s something immoral about Mr X behaving in such a way, to a woman-replicant doll. And it’s not just that it seems disgusting, or that it might increase his likelihood of behaving badly towards actual women.

There’s a deeper kind of badness – relating to how the doll is designed to replicate a woman. And this returns us to the idea, implied above, that humans hold obligations of respect to the living things around us, which extend beyond ‘the particular’. Yes, in the case of eating meat for pleasure, the failure of respect most clearly tracks the treatment of the body of some particular once-living creature. But eating its meat is also, again, to say that this type of creature is the type of creature whose dead bodies we can eat for pleasure. Similarly, Mr X’s behaviour towards the woman-replicant represents a failure of respect towards womankind.

I need to mentally distance my meat-eating from my thoughts about the creature I’m eating

This carries to other examples of people behaving towards replicants in ways that would be immoral if the targets of their behaviour were the actual creatures the replicants represented. Imagine a video game in which players could choose to stray from the game’s purpose, and torture virtual humans or animals, as they passed by, for added ‘entertainment’. Again, I don’t need to suggest that this type of gameplay should be illegal to emphasise that badness seems to be involved. And I don’t need to suggest that all kinds of virtual ‘harm-doing’ – from accidentally stepping on virtual bugs, to protecting your avatar in self-defence – are necessarily wrong.

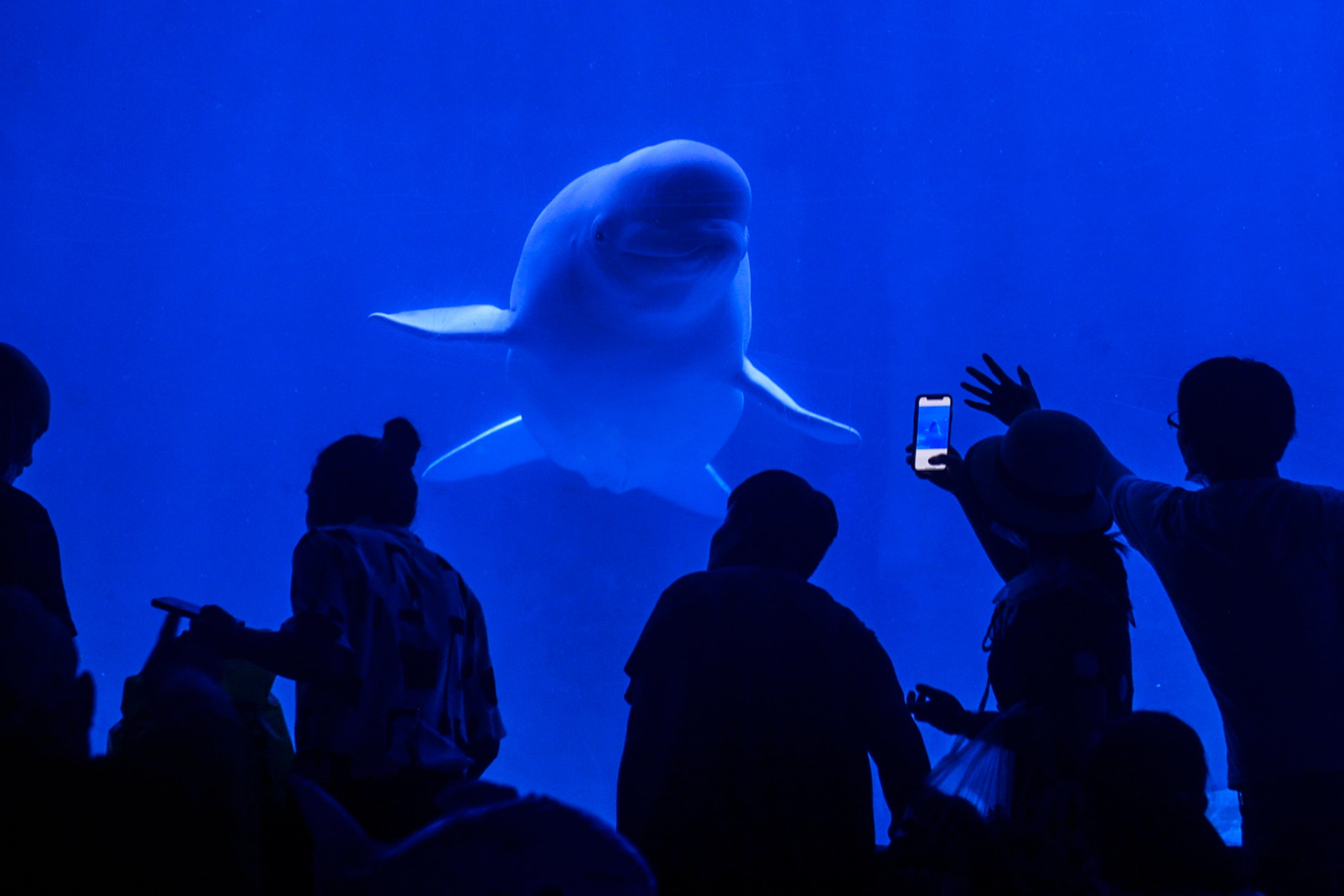

So, what does this mean for lab-grown meat? A lab-grown steak isn’t part of a once-living thing, any more than a sex doll could have ever been alive. But, by eating it, aren’t we disrespecting the type of living thing whose flesh the fake meat is designed to replicate? Don’t we fail morally in the same kind of way that the doll-abuser does?

There’s an important difference. I imagine I’m not unusual in needing to mentally distance my meat-eating from my instinctive thoughts about the creature whose body I’m eating. I feel this most strongly when faced with a whole animal: a tiger prawn in a pan with its little black eyes and antennae intact; a pig on a hot metal spit. How I wish that this thing I love – cooking and eating meat – were not tied to the bodies of once-living creatures. If only I could be sated by carrots or stones.

My desire for sufficiently convincing meat substitutes, therefore, derives specifically from my hatred of the fact that meat comes from the once living; from my guilt at my failure of respect. Whereas I assume this isn’t the case with sex-doll abuse. Mr X acts in that way towards the woman-replicant because, surely, he finds appeal in the idea of doing so to actual women – even if he hates himself for it.

Perhaps the lab technicians will save me, then, after all? It seems that, not only in terms of welfare concerns, but also in terms of showing respect, eating lab-grown meat is better than eating dead animals. Nonetheless, as long as the technicians’ goal is to recreate the exact qualities of the bodies of animals – those flavours, smells, textures we meat-lovers crave – then disrespect remains when we eat these products. We’re not talking about gingerbread men or chocolate bunnies, here. Lab-grown meat isn’t too good to be true, but it does seem too true to be good.