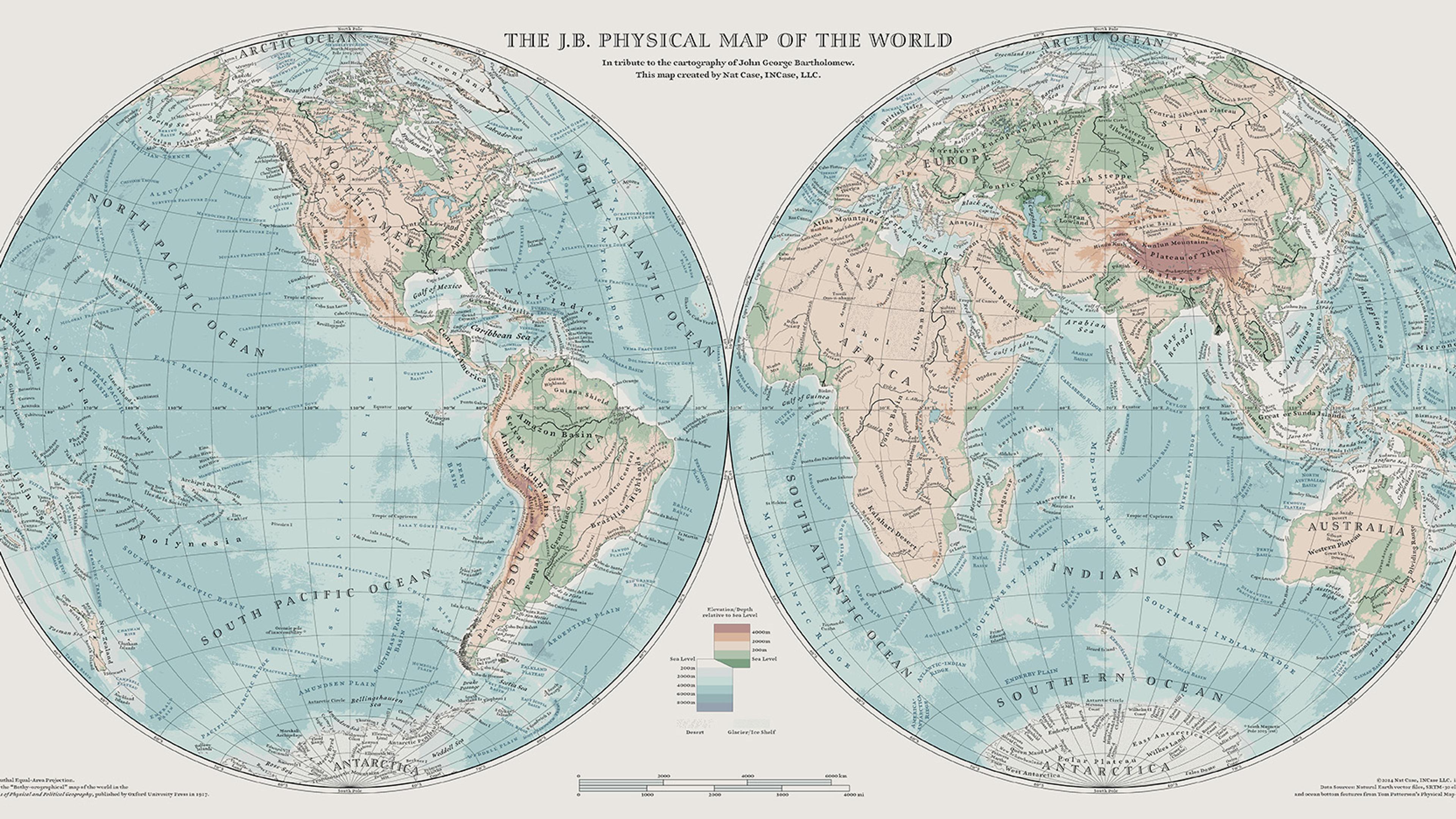

I like to think I make good maps. My former employer’s motto is ‘Life’s too short for bad maps’, and I’ve carried forward that idea into my freelance practice. It’s not my only option: I could emphasise low price, speed of turnaround, interoperability with different computer systems – really any number of things. But I emphasise quality of final product, and I’m in good company. A lot of cartographers like to work on ‘good maps’.

How can I tell if a map I’ve made is good or not? One approach is to ask how my map matches accepted standards, but in practice there really aren’t global standards, and the standards that do exist tend to be about uniformity rather than excellence; they go for ‘acceptable’ rather than ‘good’. I’ve heard people say things like: ‘It isn’t a real map if it doesn’t have a north arrow and a scale,’ but this is akin to the argument that it isn’t a real essay unless it follows the high-school five-paragraph essay format. Anyone who does serious work of any kind knows that that kind of formulaic structure is either equivalent to a safety checklist (needed because people forget crucial little things) or it functions as training wheels made to be taken off in the service of a better finished product.

So, no, the cartographers I know really don’t spend a lot of time referring to standards as a measure of quality. Another simple metric is: will people pay for this? At my former employer, a publisher of maps sold at retail, the most basic measure of success was whether a map sold or not. Now that I mostly make custom maps for clients, the question is more whether they think it’s worth paying my quoted price, whether they like the result, and whether they would recommend me to others or hire me again.

Money talks, but when I talk to professional colleagues about how to make better maps, we’re not trying to sell maps to each other. We look at each other’s maps in a way that reminds me of my past as an art student: through the framework of critique. We ask things like: ‘What is this map trying to do, and does it do it well? Does it all fit together? Is it well balanced? Is the visual hierarchy – from background to foreground – clear? Does the style match the purpose and audience?’ These are pretty broad questions, with soft edges, and so our answer to ‘Is it a good map?’ is seldom simple.

Critique is different from value judgment in an important way: it’s much more social. When I talk with colleagues, or with my employer or clients, we are not just looking at the product. We’re also listening to each other. People don’t hire other people to do work for them solely because of technical skill; they also hire them hoping they will be good to work with. The same is true in the other direction: if a client is a pain in the ass, I will either decline to work with them again, or add a ‘PITA’ surcharge. And it applies not only vertically, but laterally. The people I work with as co-vendors – printers, book designers, web engineers, software suppliers and data sources – judge me and I judge them, deciding whether they and I are worth the effort for what we get in return.

When I am providing a service making a map for a client, that social relationship is central

I say ‘judge’ here, and that sounds cool and calculating, but it’s often as simple as: ‘Do I like this person or not?’ Ideally, social relationships have warmth to them. I genuinely like most of the people I work with. There’s a calculus in there too, as there is in all friendships. But it’s a warm calculus, not just purely transactional. Indeed, if it is purely transactional, if the calculus gets too calculating, that in itself can make the relationship less pleasant. ‘Negotiation’ is also a cool, calculating word. But it is, essentially, what goes on in the web of relationships that makes up our work. Personally, I like to think of that negotiation as more of a dance, balancing the weight given to all the various people I have partnerships with.

The balance between these two modes of evaluating quality – social and object-based – depends on how the buyer and the maker are related socially. When I go to a grocery store and pick something off the shelf, I have virtually no social context for my choice: I don’t know if the people who made this box of breakfast cereal are kind or cruel. On the other hand, my comfort and desire to assess character is central to choosing something like a therapist. The same holds true for maps. Whether an object is for sale or free, if I pull it off the internet or off the shelf in a bookstore, it floats into my life without social context. But when I am providing a service making a map for a client, that social relationship is central.

One of the key sources of insight for me in thinking about good work has been the field of moral psychology. The past couple of decades have seen the development of a new set of competing theories that ask the question: ‘Why do human beings as a species have morality?’ Details vary from theory to theory but, in every case, social relationship is key. We feel moral right and wrong, and in particular we feel it in our relationships. We judge other people because we see their behaviour in relation to ours, through the lens of morality.

It’s a little odd to me then that morality is so often framed not in terms of relationship, but in terms of an abstract or higher principle, as it acts on individual conscience. We might tell a toddler ‘because I say so…,’ but when we want to invoke that kind of morality in an adult social situation, it tends to be within the larger framework of law or codified ethics, which supersedes the person-to-person relationship in question. It’s not that we won’t stage an intervention with a loved one or friend who is going off the rails, but that tends to be a rarity, and is often a highly loaded drama. We value our moral autonomy, and bringing together personal social relationships and moral judgment is a recipe for seeming judgmental and sanctimonious.

You might think there’s not a lot to get moralistic about in the world of mapping. You would be wrong. For decades now, various critiques have been raised about cartography, its history, its current practice, its complicity in the evils of the world, and cartographers’ degree of responsibility. On the one hand, cartographic history in the West is bound up with institutions that created maps to prosecute war, subjugate colonies, extract wealth from the earth regardless of who was already living there, and manage mass social engineering including a large-scale oppression. Maps can also be tools that create individual agency by giving any map-reader a manager’s view of the world. That part tends to be noncontroversial. It’s who we work for and with that causes some people to raise concerns.

We want our own moral stances to be embedded in the structure of the universe

The past few years, I’ve been involved with work on ethics in cartography, including helping organise a commission as part of the International Cartographic Association. A lot of what people mean by ethics in the field involves the sort of relationships I mentioned among cartographers, their employers, map users, and the subjects of our mapping. Issues include what should and should not be mapped, respect for intellectual property, how we portray information, honesty, clarity and respect for the humanity of everyone we’re working with. Which is to say, the focus is on being good and decent people in the networks we work within. Where it becomes harder to reach agreement is where two systems actively conflict with one another, either in practical terms, like territory (for example, coming to agreement on how to portray Israel/Palestine, or disputed boundaries in the Himalayas), or when participants in two systems perceive each other as morally bankrupt (for example, fossil fuel companies and climate activists). It is hard to develop social relationships across an armed border, and so any agreement in terms of ethics also becomes harder. Neutral zones become no man’s land.

To a great extent, neutrality is built into what modern Western cartography is about, much in the same way that it is built into librarianship. Libraries don’t usually have a special label on spines that says: ‘This book is about evil.’ Santa Claus may have a list saying who is naughty and who’s nice, but the census office doesn’t. And we want both: we want to be able to view the landscape clear of other people’s moral stances, but we also want our own moral stances to be embedded in the structure of the universe.

Even when we create products that are sold to customers we never meet, we are part of an exchange that presumes quality. That is an easy case to make if I knowingly sell you ‘medicine’ that ends up killing you, or canned food that will give you food poisoning. It is just as true in less consequential cases. Consider how we view a used car salesman who sells us a lemon. We may fall back on legal remedy, but we do so because we have been cheated, because we have been lied to, because we have been morally done wrong. Good-faith effort to make things that work is a moral issue when it’s framed in a wider social context. In a sense, it is the anonymous marketplace that makes this hard to see: the character of the person who made that breakfast cereal is hidden from us, but if they hurt us with that cereal, they have done us wrong through that anonymous relationship.

On the other hand, while we may frame big moral issues as absolutes, we need to acknowledge that we are constantly negotiating even with them. Those big moral absolutes may claim primacy above all others, but they are still constituents competing with other constituents for attention. Moralists especially may claim that framing morality this way leads to relativism and slippery avoidance of responsibility, and it certainly can do that, but it is also part of fitting in those absolutes, those big-picture principles that we want to think come from above, into the heart of our moral life, which is the web of relationships with other people.

I like to think I make good maps. I hope and try to be a good person in relationship to my moral model of the world. I can try to judge this based on some kind of scoring system, some set of standards but, in the end, all of it boils down to that negotiation, that dance, which I’m constantly carrying out and everyone else is carrying out around me. If I pretend that my work is all that matters, I cheat myself in one way. If I pretend that moral principle is all that matters, I cheat myself in another.