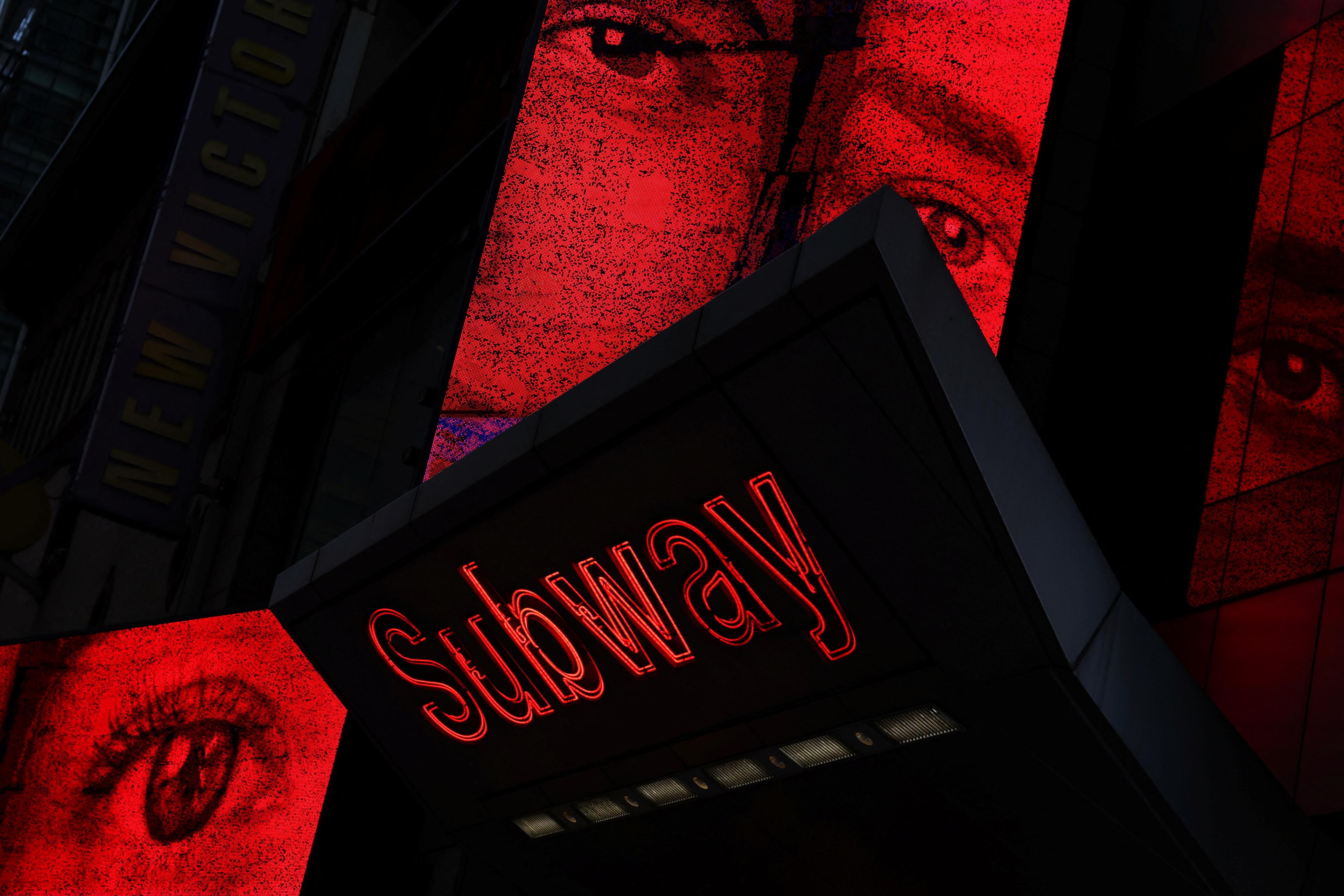

The treatment was supposed to start at 8am, but many of the participants arrived at the airport much earlier. They didn’t want to miss anything, and some say they were too excited to sleep in anyway. After hearing of the programme through local media reports, they are the first 138 people of more than 700 who have signed up for a one-session, group treatment programme to combat their flying phobia. Because of their fear, most of them have not flown for years; some have avoided air travel all their lives.

Now they are gathered here in a congress hall at the airport where I provide them with information about the meaning of anxiety and fear, as well as the typical cognitive and bodily symptoms associated with a fear of flying. I also talk about fear-maintaining processes and dysfunctional ‘safety behaviours’ (strategies that might bring relief in the short term, but ultimately prolong the problem), such as taking tranquillisers or drinking alcohol.

Then the flight captain and crew enter the scene, ready to respond to participants’ questions: What actually happens in the event of a medical emergency on board, or if an engine fails? Can an aircraft be struck by lightning? Is that dangerous? What happens in a severe storm?

People have a lot of questions and, for most of them, the staff can give the ‘all-clear’: flying is extremely safe, and the aircraft and crew are well prepared for virtually any eventuality. After that, it gets serious.

Now, I say, it’s time to board the ‘exposure’ flight, to gain a new and anxiety-relieving experience in dealing with your fear of flying. A specially chartered plane and a team of 20 therapists are already waiting at the gate. The vast majority of this first batch of participants, more than 120 in all, dared to take part. Security check, boarding – everything is as it would be on a normal flight. When the doors of the plane are closed, however, tension is palpable. Some stare ahead, some cry, and others concentrate on the talks offered by me and the other psychotherapists.

As the plane accelerates for take-off, it suddenly becomes extremely quiet and when two participants in the front row join hands across the aisle, many others do the same. This moment seems almost choreographed. At cruising altitude, the atmosphere of most participants relaxes noticeably and, supported by the professionals, some brave folk begin some planned exercises, such as looking down out of the window, daring to unbuckle their seatbelts and walking across the aisle – things that people previously thought they could not do under any circumstances.

After two hours and a round trip over Germany, the plane lands safely where it had started and the range of emotions of the participants goes from total relief to pride and happiness. Follow-up studies will later show that, for more than 70 per cent of the participants, this one-session training, only part of which I’ve described here, led to complete or at least partial remission of their fear of flying, and they no longer avoid air travel.

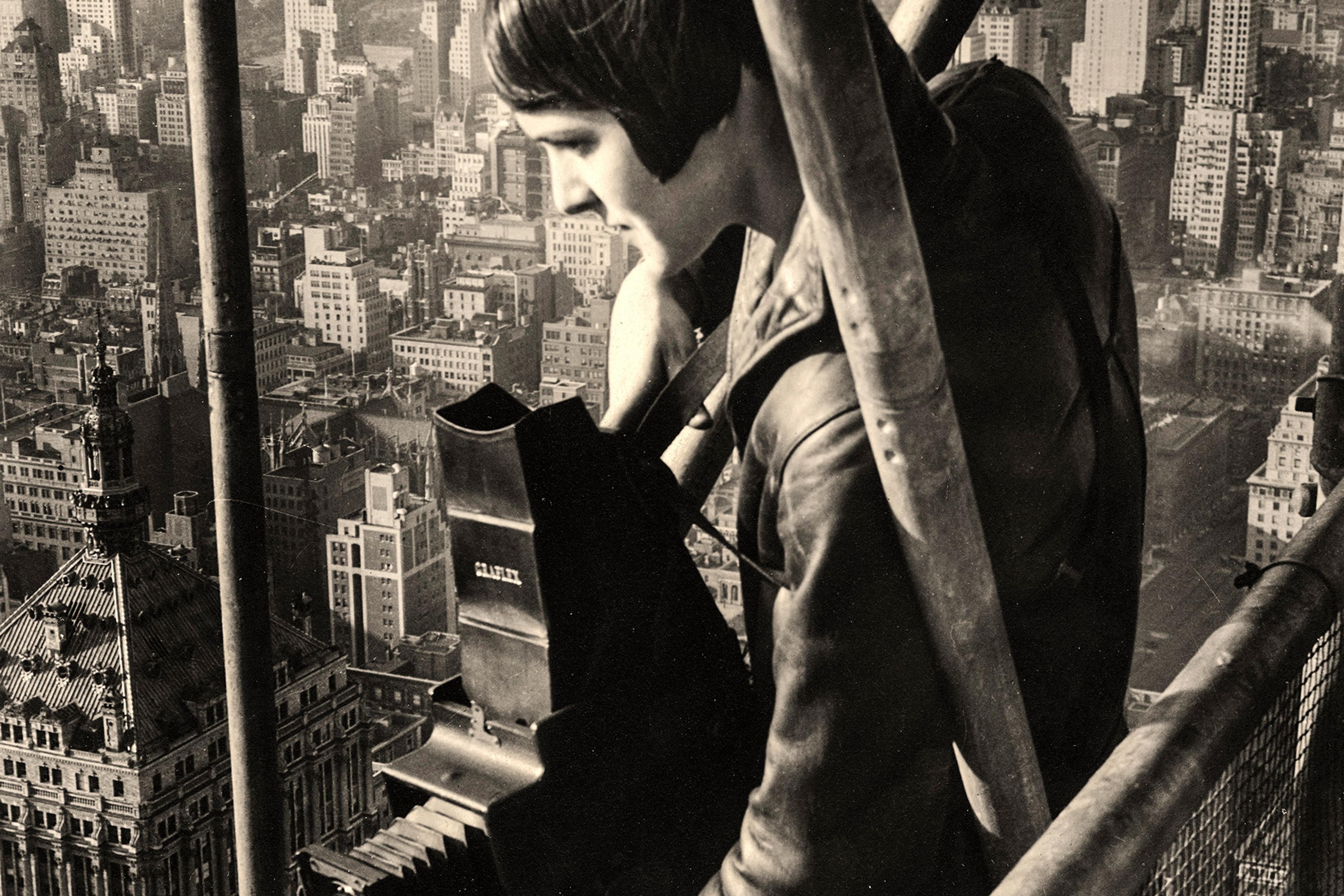

My colleagues and I call this approach an exposure-based large-group one-session treatment (LG-OST). It builds on the remarkable advances made in the development of highly effective cognitive-behavioural treatments (CBT) for various mental disorders. So-called ‘exposure strategies’ are at the heart of these approaches. According to Michelle Craske, one of the worlds’ leading experts in the field, exposure therapy refers to ‘repeated, systematic exposure to cues that are feared, avoided, or endured with dread’. Whether the therapy is delivered in vivo (ie, involving actual objects, events or situations), in sensu (ie, using the imagination – for example, to conjure traumatic memories or obsessional thoughts), or it’s interoceptive (ie, focused on the feared bodily sensations), it should provide the patients with new, anxiety-reducing and fear-relieving experiences that violate their fear-evoking expectancies – such as patients with a fear of heights (acrophobia) predicting that ‘If I step too close to a precipice, I am pulled into the depths.’

Current research suggests that successful exposure treatment leads to the formation of a new memory trace – ie: ‘Even if I step very close to a precipice, I do not lose control of my body’ – in which the formerly feared stimulus (the precipice) is no longer associated with threat. This new learning can happen very quickly. Already in the 1980s and ’90s, the Swedish psychologist Lars-Goran Öst and his team showed that most phobic disorders could be treated just as well in one session of only a few hours as in multi-session formats, and just as effectively in small groups as in one-to-one therapy. Since then, the positive effects of one-session treatments have been demonstrated not only for phobias, but also for other forms of excessive anxiety, for example panic attacks resulting from traumatic experiences.

After an exposure treatment, between a half and two-thirds of patients are deemed to no longer suffer from an anxiety disorder or they show significant improvement. This is a blessing when considering the life-limiting, long-lasting, progressing and – as increased suicide rates among anxiety patients show – sometimes even life-threatening character of these disorders. Moreover, they are very common. In the European Union, with a pre-Brexit population of approximately 513 million, about 61.5 million people suffer from one of these disorders. Phobic disorders, though commonly considered to be rather mild anxiety disorders, account for more annual days lost from work, on average, than chronic heart disease or lung disease. It is reassuring that professionals know how to help patients with evidence-based treatments in the best possible way. Unfortunately – and for various reasons, including a lack of suitably trained therapists – only very few patients have the benefit of receiving such treatments.

This is where my research on LG-OSTs, led jointly with Jürgen Margraf, comes in – these treatments hold the potential to provide evidence-based psychotherapy to patients quickly, effectively and en masse. Just like its small-group predecessors, we conceive of LG-OST as a ‘self-contained’ psychotherapy session to be done together with all patients in one day. Psychoeducation, exposure and relapse-prevention are core elements. LG-OST can also contain certain training elements – for example, relaxation skills.

As with the fear of flying treatment, the initial psychoeducation phase is usually divided into two parts. In the psychotherapeutic part, patients receive information about the utility and protective function of fear and anxiety, as well as on factors that cause and maintain their specific anxiety problem, such as how for people with contamination anxiety, short-lived relief from handwashing can contribute to the maintenance of their compulsion to wash.

In the next phase, an expert on the specific phobia topic answers frequently asked questions – for example, in the case of arachnophobia, a biologist might dispel the myth that spiders sometimes crawl into open mouths during sleep.

The ensuing exposure phase is usually preceded by an assessment of each participant’s individual fear-inducing expectancies. For example, patients with social phobia would be asked to describe in detail their catastrophic expectancies – if, for example, they were to give an unprepared speech in front of the other participants, they might predict ‘I won’t get any sound out’, ‘The others will look bored’, etc. Respective exposure exercises are then tailored to the specific anxiety symptom, therefore containing quite different contents. For example, whereas the flight represents the main exposure element in the fear of flying LG-OST, for blood-injury and injection fears, the exposure part would include watching phobia-relevant images and video sequences dealing with injuries and blood-takings, and then culminate in having the possibility to have blood drawn by a medical professional (using a previously learned tension strategy to prevent fainting). Finally, patients get concrete advice on ways to prevent future relapse.

So far, we’ve conducted LG-OST programmes targeting different phobic fears (spiders, dental treatments, blood-injuries or injections, heights, flying and lectures), as well as social phobia and washing compulsion. The group sizes ranged between 30 (fear of heights) and 138 (fear of flying). I was the lead therapist for all programmes, supported by a team of clinical psychologists and psychotherapists that varied in size from 4 (spider fear) to 35 (fear of flying) professionals.

We’ve found that LG-OSTs lead to substantial reductions of phobic fear, avoidance of feared objects and situations, as well as ameliorating patients’ impairments in the short and long term. You might think that, if you gather a group of people together with a shared, intense fear, there could be a risk of mass panic or contagion effects, but these worries proved unfounded in all the LG-OSTs we conducted.

Of course, there were participants in all the LG-OSTs who showed severe fear reactions that required immediate therapeutic or, in the case of the LG-OST targeting blood-injury or injection phobia, even medical care – while watching a video during the psychoeducation phase, in which a doctor reported on the process of taking blood, eight of our participants fainted (even though no blood or injection needles were visible). We were prepared for this – the doctor and two nurses who were present were able to quickly stabilise the people, and everyone continued the training. This and similar incidents showed us again and again that therapeutic work with people in large group contexts requires careful and well-thought-out preparation.

However, we were also touched every time to see how empathetic, helpful and motivating the participants were to each other in these situations. When the medically supervised participants returned to the hall after a short time to continue the training, they were applauded by the others for their courage. Participants who initially did not dare to go up in the basket of a fire escape as part of an LG-OST against fear of heights were cheered on by the others and, as in the case of the fear of flying LG-OST, in which the participants held each other’s hands at take-off, they were very gentle and supportive of each other, especially in moments where someone had just suffered from their fear even more than themselves. In keeping with this, many participants reported after the treatment how relieved they were to see that there were so many other people affected by the same problem and, above all, that during the training there were still people with larger fear and anxiety than themselves. Inspired by these reports, we’re currently investigating whether, beyond ‘classic’ factors such as the violation of fear-inducing expectancies, there are specific (group) factors that contribute to the effectiveness of the LG-OST programme.

There is still a lot of work to do. Despite our promising initial findings, it remains to be proven whether LG-OST is a feasible and effective treatment for anxiety disorders beyond phobias. Moreover, the ‘best’ therapist-to-patient ratio still needs to be calibrated. And most importantly, LG-OST effectiveness needs to be improved further, because not all participants benefited to the desired extent. The cost- and resource-saving aspect of LG-OST, however, is obvious. Regardless of whether LG-OST would be used as a standalone treatment, or within a framework of stepped care in which all patients initially get LG-OST and only those who do not sufficiently benefit subsequently progress to individual treatment, its use would relieve the burden on public healthcare systems. The LG-OST procedure gives many patients access to an evidence-based anxiety treatment they otherwise might not receive – and it helps them lose their fear of being alone with their problem or even being belittled for it.