The phrase ‘Black is beautiful’ is a familiar political slogan, but it was also a social movement, and later a wildly successful marketing tool. The coinage dates back to the Naturally ’62 fashion show in Harlem, New York City, which eventually spread across the country. It challenged mainstream ideals by featuring Black people in conventionally white roles – not just on the catwalk, but as photographers, designers, musicians. At a time when the Miss America beauty pageant still, in practice if not officially, operated under the rule that ‘contestants must be of good health and of the white race’, the Naturally shows broke new ground.

As much as Black Is Beautiful took aim at the mainstream, it also opposed those Black elites who equated beauty with lightness. Barred from mainstream fashion and beauty exhibitions, Black teenagers and women smiled, waved, and glided across stages at local churches and Black colleges, competing over who had slimmer figures, lighter complexions and the silkiest hair. The historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham coined the term ‘respectability politics’ to describe just this sort of kowtowing, designed to prove the worth and humanity of Black people through good manners, morals and proper grooming. The goal was to make Blackness more palatable and less confronting, to quietly fit into white America.

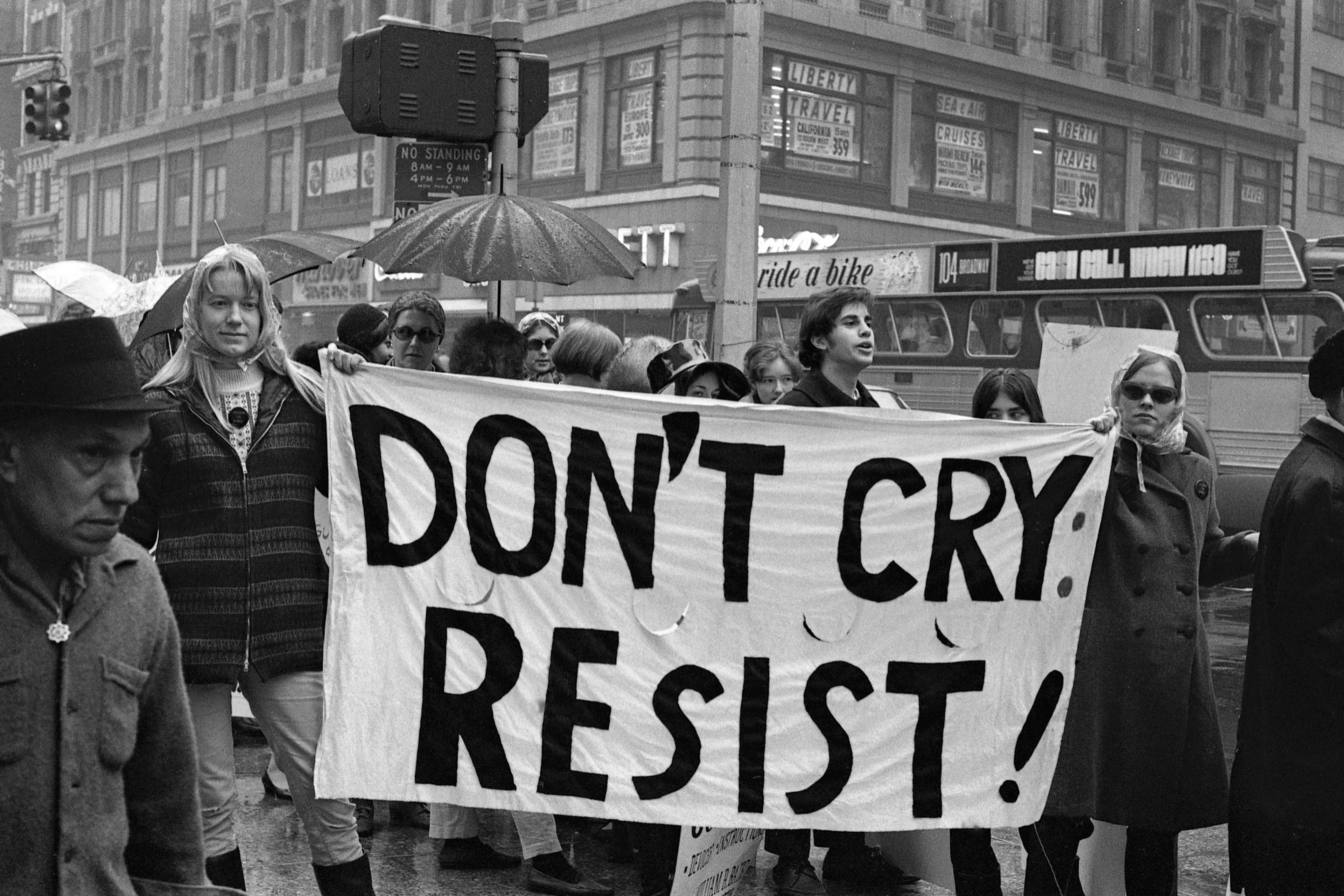

Indeed, the Black Is Beautiful movement of the 1960s was intentionally impolite, a loud rejection of respectability. The historian Robin Kelley pointed out that Black women in art and fashion at the time, including Miriam Makeba, Nina Simone and Margaret Burroughs, turned heads when they adopted ‘naturals’ – a cropped, unprocessed hairstyle that paved the way for the larger Afros that would become synonymous with the Black Power movement. The styling was an element of what the historian Tanisha C Ford described as ‘soul style’ – a look inspired by pick-and-mix influences taken from African cultures, which coalesced around bold, brightly coloured African-inspired prints, loose-fitting clothing, beaded accessories and unprocessed hair.

The idea to launch a series of Naturally shows to flaunt this ‘soul look’ on models with darker complexions, kinkier hair and curvier figures did more than feed off the popularity of mainstream and European fashion showcases. The shows were also extensions of the fashion parades of enslaved Africans during the antebellum period. In her book Liberated Threads (2015), Ford described these as colourful displays among the enslaved, who were allowed to construct and wear their own clothing for church every week. Their resourcefulness helped establish a unique tradition of pageantry and the cultural blending of European and African aesthetics with those of the Americas, which the Naturally shows depended on.

From walls adorned with African masks and animal hides to models armed with spears, every prop was seized upon to tell a story about true Blackness, to literally stage it before live audiences. Fantasies of distant places merged with Black models, photographers and musicians engaged in acts of reproduction and representation. This did more than produce a great show. It smashed the typical gaze that distorted Blackness into a fundamentally unbeautiful thing. But the shows also breathed life into problematic dichotomies between nature and artifice at the heart of Black Is Beautiful by promoting an image of authenticity as the essence of Black identity, despite what was clearly a performance on an actual stage.

The idea of naturalness, true selves and essences became paramount to Black Is Beautiful as an antidote to mainstream beauty ideals. In other words, ‘looking natural’ became shorthand for a disavowal of mimicry. It became an outward expression of what could not be seen: a person’s political consciousness, whether they were wracked with self-loathing or a self-love that got mapped onto the collective. This sort of reasoning about interiors and exteriors has its roots in Enlightenment beliefs that seeing is knowing, that we can make sense of our visual experience of each other to uncover deep-seated truths. When it comes to the look of Black bodies, it’s been used to make all sorts of claims, not least white supremacist ones about our innate inferiority.

Black Is Beautiful was a progressive movement that popularised a somewhat backward view of Africa, or at least an imagined African past, that had less to do with modern Africa and more with identity politics. After all, plenty of Africans didn’t wear dashikis or Afros until they too were influenced by what became a global movement. Even as an image of authentic Blackness was elevated, its very production involved imitating an imaginary African style using techniques that were themselves a mixture of influences, or adopting African-sounding names that better represented one’s Black identity. In other words, imitation was unnecessarily under attack even as it was relied on.

Similarly, Black Is Beautiful proponents treated naturalness as a retreat from the excesses of modern Western society. As a counterbalance to abundance, they maligned artifice, which is all about revelling in what we don’t need or naturally possess. But locating excess, imitation and artifice in the West meant turning a blind eye to the rich styling practices found across Africa. And that’s just it: the Black Is Beautiful movement did revel in pageantry and fanfare, adornment and spectacle, imitation and even excess. They just called it ‘natural’.

Its artifice belonged to the Black Atlantic. The historian Paul Gilroy has traced the many intellectual and cultural currents between the United Kingdom, the United States, the Caribbean and Africa, which were spurred by the slave trade and still resonate today. This transatlantic African diaspora, Gilroy argues, is concerned with the movement of people, ideas and practices across national borders, more than the making of a single origin story that appeals to cultural purity or the longing for return that characterise other diasporas. For example, the scholar Monica Miller noted that enslaved people clung to small objects such as beads, trinkets and fabric swatches from home to preserve cultural memory and weave it, sometimes literally, into their new lives. Even in the midst of enslavement, the power of artifice survived across generations and continents, mingling with European, Indigenous and Caribbean influences along the way.

Claims to authenticity aside, the Black Is Beautiful movement popularised this sort of melding wrought out of the circulation of people and ideas. It’s right there in the African-Dutch wax prints and the cornrow braids. Applying a similar lens to beauty politics as Gilroy applies to cultural products such as jazz, we see the same hybridity. It’s the blending that comes naturally, not the purity.

In terms of cultural politics, however, the ‘naturalness’ underpinning the Black Is Beautiful aesthetic was pitted against the impure and artificial. Praise for modesty, lighter complexions, finer facial features and straightened hair were lumped in with antiquated respectability politics: women who lightened their skin were seen as disturbed and fake. And women who wore wigs and hairpieces were viewed as chasing standards rooted in white European supremacy, the thinking being that someone would imitate their oppressor only if they were mired in self-shame. This reasoning forecloses other motives, denies Black women experimenting, or wanting to look and feel modern by straightening their hair using new beauty technologies that allowed for possibilities beyond those of nature.

An overconcern with women’s appearance as a mark of personal and collective pride contributed to a weakness of the movement, and eventually its decline. According to scholars such as Kelley, Black Is Beautiful unintentionally blurred the line between women and men by promoting a uniform look that became the look of Black militancy. While the Afrocentric styling preserved some markers to outwardly differentiate male and female bodies, the shared embrace of loose-fitting attire with identical patterning and hairstyles such as Afros and cornrows proved too radical a disruption of gender norms. Black women went from ‘looking natural’ to ‘looking masculine’.

Is this a feminist issue? Yes, but not in a clear-cut way. In The Beauty Myth (1990), Naomi Wolf described beauty ideals as social myths, as a type of social currency that regulates women by undermining our sense of self-control as we chase after culturally prescribed images of unattainable beauty, including so-called natural ones. For Wolf, women are stunted by this pursuit – made anxious, neurotic, unhappy – and liberated only once we shatter, or at least better manage, social expectations about the way we look.

This sentiment echoes earlier feminists such as Betty Friedan, and we see iterations of it today in popular culture. In the song ‘Pretty Hurts’ (2013), Beyoncé croons that chasing outward beauty is damaging because ‘you can’t fix what you can’t see. It’s the soul that needs the surgery.’ In the music video, she presents herself as a beauty-pageant contestant with a plastered-on smile, surrounded by other hopefuls. Backstage, they bicker, cry, pop pills, vomit, and swallow cotton balls to stave off hunger, before appearing on stage before a panel of male judges. It ends with a shorter-haired Beyoncé removing make-up in front of a mirror and reminding us that the trick is to be happy with yourself without the mask.

But can’t we be happy with our masks too? Masks can be self-preserving, playful and expressive, a refusal to bare ourselves and go deep. The call for less adornment, fewer chemicals, less Spanx, implies that such masking is unhealthy, even ugly. The feminist scholar Ela Przybylo calls on women to disruptively revel in the oppositional, to ‘strategically deploy ugliness’ to unsettle beauty norms that inform how women are expected to look and behave in public spaces. Przybylo presents this as a choice, that women play at being, looking and sounding ‘ugly’ to unsettle popular conceptions of femininity.

Yet opting in and out of ugliness – or femininity, for that matter – is impossible for women of colour who call into question binaries such as pretty/ugly and feminine/masculine without trying to, let alone being strategic about it. Black women, in particular, have no choice but to deconstruct these binaries, because Blackness already involves audacious reworkings of myriad cultural and political influences. Blackness is, after all, an amalgam of the natural and unnatural, real and fake, beautiful and unbeautiful, depending on how you define the terms. It’s in perpetual conversation with itself and the outside, which helps give it its fuzzy shape. This, again, is the Black Atlantic.

Intellectual and political movements aside, Black women continue to expertly mix the natural and artificial out of necessity as much as artful self-expression. Today, across social media, you’ll find hundreds of thousands of videos about Black women’s bodies, in particular our hair. The natural hair movement is a modern take on Black Is Beautiful, and similar contradictions abound over what makes one person’s hair more or less natural, which natural looks are held up as more or less beautiful, and whose business it is anyway. There is an insistence here on a sort of sincerity from Black women in exchange for recognition.

Still, you’ll find just as much social media content featuring Black women’s weaves, wigs, make-up contouring, acrylic nails, waist trainers, eyelash extensions and filters of all kinds, content that seems to push back against the ‘natural’ trend by suggesting that women can be part of nature without being limited to it.