Imagine your perfect society. I often put this to the people in my life – it’s good dinner-party conversation, a memorable opening with a new acquaintance, and can make time fly on a long train journey. Some have told me they see lush palm trees stretching toward a luminous blue sky, while others envision miles of rolling hills blanketed in thick snow. Uncannily, all respondents below age 10 envision a magical daily delivery of all the chocolate their hearts desire, in contrast with an older woman I know who dreams of exchanging the produce of her imagined backyard farm with her fellow neighbours. Some can think of nothing better than giving up work altogether, and others imagine finally finding fulfilment in a job of passion rather than necessity. What do you see? My question, in short, is: what does utopia mean to you?

Coined by Thomas More in 1516, ‘utopia’ described a fictional island of total perfection. To More, utopia was a society free from flaws, untainted by social ills, and harmoniously in balance. Yet, deriving from the Greek ‘ou’ (not) and ‘tópos’ (place), the term can be approximately translated to mean ‘nowhere’. The possibility of reaching utopia was so unlikely to More that, in the very nature of the term itself, he precludes its existence.

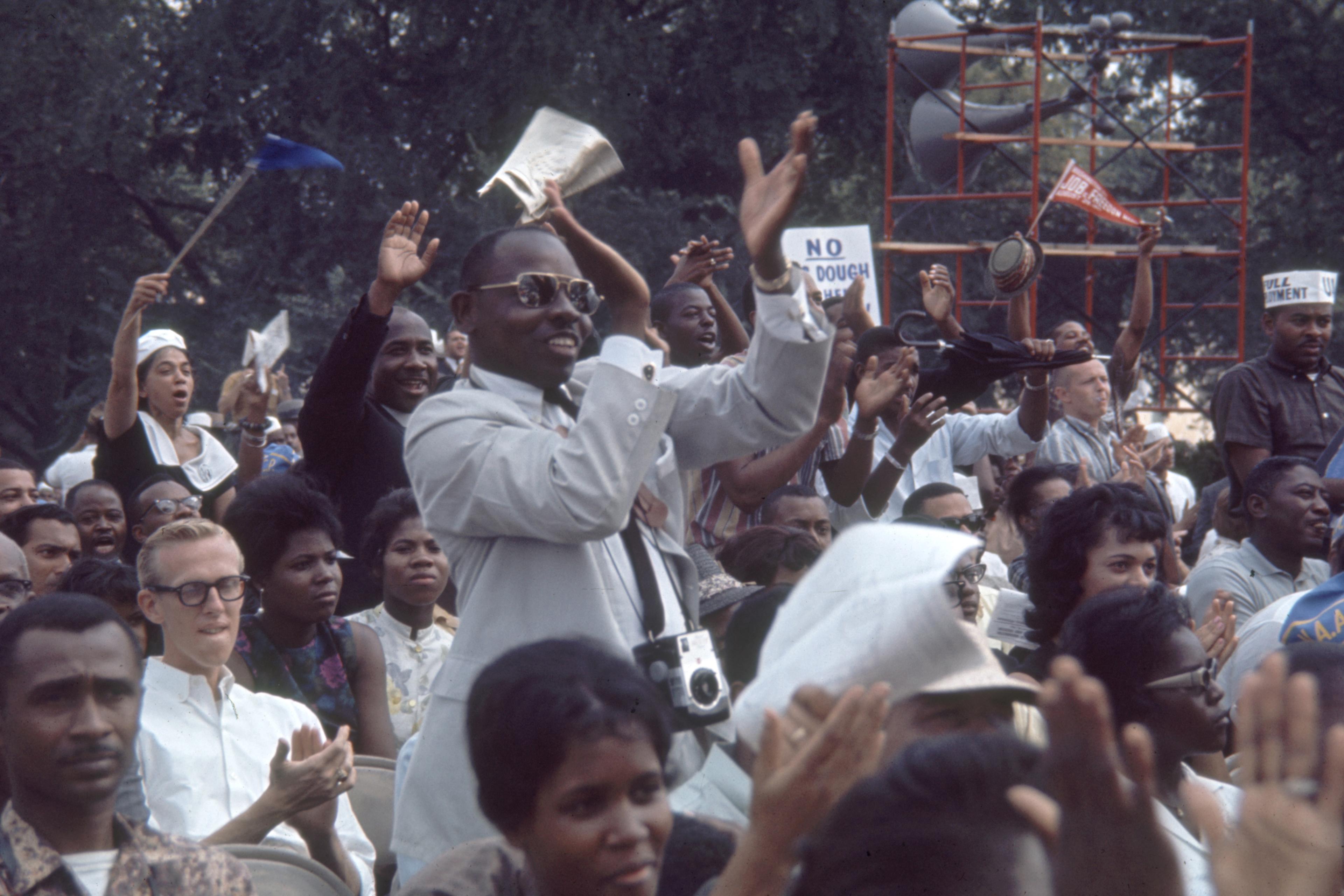

When trying to characterise the contemporary moment in politics, utopia isn’t a word that springs to mind. When national politics is becoming increasingly polarised, global conflicts are escalating to new temperatures, and the toll of the climate catastrophe grows deadlier, the mere mention of utopia risks generating side-splitting laughter. In fact, to even speculate whether a utopian world is in our periphery seems so absurd that ‘utopian’ has taken on an altogether different meaning. Consider how some of today’s most searing political suggestions are all too quickly dismissed with the label ‘utopian’. Mass uprisings in the wake of George Floyd’s death in 2020 saw well-established political arguments around defunding the police and abolishing prisons enter mainstream political discussions, yet this was quickly labelled ‘too utopian’ a demand. Similarly, as climate discussions veered into the ways in which we might radically rethink our consumption to avoid climate disaster, such visions were cast as ‘utopian’ in their belief that human behaviour could ever be altered in such a fundamental way, no matter the reason. More recently, as cost-of-living crises hit globally, long-running debates about the feasibility of a universal basic income have reinvigorated adamant criticism of its ‘utopian’ implausibility.

Labelling something ‘utopian’ has become shorthand for denoting its lack of realism. To call someone utopian today is to reprimand their head-in-the-clouds, naive, optimist, daydreamer character. ‘Utopian’ has become synonymous with critique, and a utopian idea is now not a vision of a hopeful future but of an impossible one.

Such a negative view hasn’t been necessarily conjured from thin air. Utopia has a dark past – some of the most prominent pursuits of utopian societies have been failed attempts, most notably the grand narratives of Marxist Russia or Nazi Germany. Both Stalin and Hitler, though poles apart on many things, had in common the desire to pursue society’s perfectibility, as they saw it. The sheer danger to human life unleashed by their attempts, more than their failures, has left utopia with a rotten taste, stoking a fear that utopian striving tends towards totalitarian, absolutist methods. Utopia has thus come to be seen as a politics of problematic idealism, encouraging the pursuit of the ‘perfect society’, irrespective of the cost it takes to get there.

More than merely a problematic past, utopia has to deal with an equally challenging present. Contemporary politics has little place for utopia. Ironically, dystopia – in many ways utopia’s antonymic sibling – has found a much more comfortable seat in modern political discourse. Following Donald Trump’s win in the 2024 US presidential election, news outlets and social media overflowed with references to Margaret Atwood’s novel The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) to characterise a climate of fear and hopelessness surrounding women’s reproductive freedoms. Similarly, dismay over potentially impending book-banning brought Ray Bradbury’s novel Fahrenheit 451 (1953) back into headlines just as, ironically, the sale of dystopian fiction began to surge. A glance at today’s political temperament would have us believe it’s time to chuck utopia out of the window altogether. No wonder the question of whether we have arrived at the ‘death of utopia’ has been raised by numerous political theorists. Have we become apathetic about the possibility of things ever being radically different? Are we no longer concerned with the ‘betterment’ of society? Can we even imagine a path to such a society at all?

The COVID-19 pandemic proved how quickly we could learn to adopt new social rules

But scholars of utopia ask us not to ring utopia’s death knell so soon. Some not only answer the question of whether utopia is relevant today with a resounding ‘Yes!’ but even go so far as to argue that now is a better time than ever to revitalise utopia in politics.

What this first demands, however, is recognising how narrowly utopia has previously been defined and how much else it has yet to offer. While utopia can signify an ideological project seeking the pursuit of a perfect society (as in the Nazi and Stalinist examples), often neglected is what lies beyond. Utopia as a strategy for politics invigorates a praxis that is simultaneously critical, imaginative and, crucially, reflexive. Unlike the ‘grand narratives’ of utopian projects, this redefinition of utopia – focused on how utopia offers a radical new way of thinking about political engagement – poses significant affordances, especially in dark times.

Utopian thinking is a crucial reminder of something oft forgotten: that the social world is far more malleable than we think. The COVID-19 pandemic proved how quickly we could learn to adopt new social rules, and reminded us of the permeability of what we consider highly rigid social boundaries. As an example, after the pandemic sent a number of social conventions into disarray, the US ethnographer Kristen Ghodsee interrogated the nuclear family unit and conventional parenting from the utopian perspective. When the pandemic struck, many parents became more vocal about a common yet understated truth of life – parenting is hard work. With rising reports of parental stress, more young people considered opting out of becoming parents. And, tasked with meeting growing childcare demands, an ever-expanding care industry showed that the social structures around parenting were problematic, even long before COVID-19 entered the picture. Why is parenting so difficult today, when it need not be, Ghodsee asked. She noted that using utopian thinking came naturally in the pandemic when social conventions were thrown into disarray by force, serving as a reminder of the flexibility of the social rules around us. Consequently, many people began to think and act in more utopian ways, considering alternative models for how parenting might be done, and asking how we might reshape our social structures to make things easier for all, such as ‘parenting pods’ and communal nurturing.

Ghodsee’s argument is that this utopian thinking was the first step in realising that the parental status quo is not permanent, and on the horizon lie new ways of organising – by parents, for parents. This is what utopianism can contribute to contemporary politics: it can reimagine how life can be bettered at a very grassroots level by people and for people. Utopianism within politics also encourages a more politically active citizenry, prompting us to rethink our roles in shaping the world we wish for. The French utopian socialist Henri de Saint-Simon was a central proponent of the idea that the future ‘Golden Age’ would be imagined and built by man’s own efforts. In reminding us how much can be changed, utopianism equally reminds us of our own capacity do so. More political power is at our disposal than we might first think.

With this notion of change in mind, a second visible strength of utopian thinking is how it encourages us to activate new political skills. Consider the imagination exercise we opened with. What was its purpose? Well, in contrast to political messaging that encourages you to hold tight to the scarce amount you have, out of fear it will be taken away, this activation of the imagination allows you to engage with possibilities of abundance and think of how much better things could be, rather than how much worse. What we did there was set a ‘horizon’ for ourselves that, to the scholar of utopian thinking Fátima Vieira, is one of the central features of utopianism. Vieira argues that utopian thinking is composed of four modes. First: ‘prospective thinking’, whereby this utopian ‘horizon’ is defined; crucially, this horizon is one that never comes to pass but sets imaginative and desirable heights, which invigorates the act of utopian thinking. Second: critical thinking, which demands an interrogation of the present. So, far from the accusations that utopian thinking is unrealistic, in fact it involves confronting reality frankly. Third: holistic thinking, which says that society works as a whole of composite paths, so any and all incremental actions must be aware of the interconnected society upon which they have consequences. And finally: creative thinking, which keeps alive the ‘What if?’ possibilities of the future, just as our foray into our own imagination allowed us to do.

Utopianism encourages a dimension of hope in modern politics

While making a grounded critique of the present, then, utopian thinking encourages us to engage different skills in our politics, bringing in imagination and creativity, which are all too often suppressed as ‘non-political’ behaviours. In Ghodsee’s description of parenting pods and communal living, we see creativity being used to respond to challenges, new and old, in the social arrangement of parenting. Again, these ideas do not remain in the imagination. As Ghodsee points out, childcare and free education – now part of everyday reality – were once flights of utopianism. Thus, as the political scientist Michael J Coyle suggests, the idea that utopian imagination necessarily precludes a grounded politics is false. Utopian thinking is not wishful thinking but, grounded in the realities of the present, it simply allows creativity and imagination to enter discussions about the status quo and its flexibility.

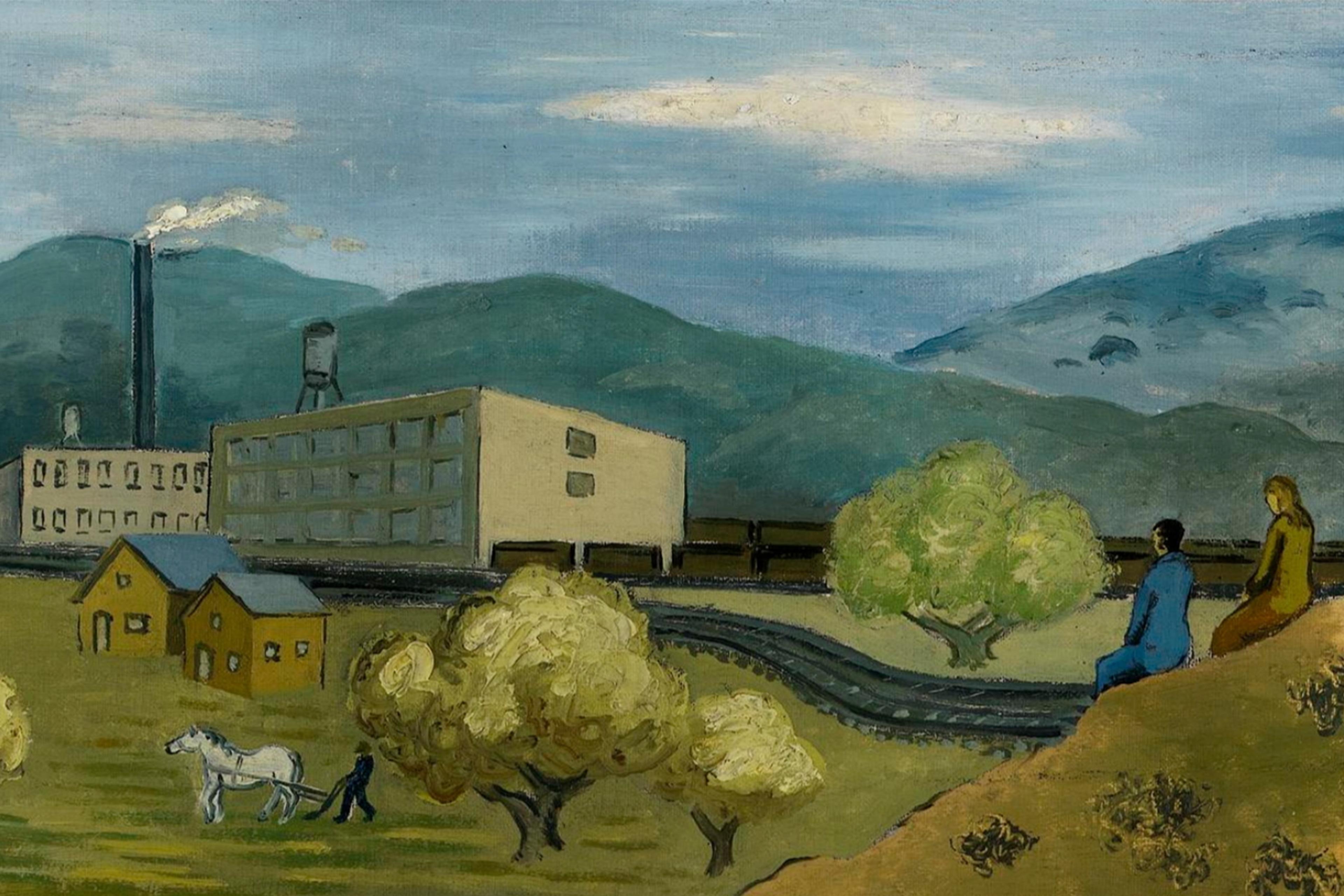

Finally, though perhaps most appealing of all, utopianism encourages a dimension of hope in modern politics. Given the seemingly deep-rooted despair in politics, the popularity of dystopia is understandable. Yet, as the legal scholar Marta Soniewicka suggests, utopian thinking shows itself as a form of ‘radical hope’ that trusts in the possibility of a better future, even if it’s not something we can yet envision or understand. Utopianism, then, is a sort of resistance to a politics that makes the possibility of transformation appear closed off. As Rebecca Solnit has written: ‘Violence is the power of the state; imagination and nonviolence the power of civil society.’ So, utopia’s role in encouraging imagination, creativity and hope functions as the most crucial part in enacting any change – invigorating the very consciousness of the people who will the change into being. No wonder that utopia is often iterated in artwork, music, film and literature. A prominent branch of utopian thought is Afrofuturism, which battles racism by providing hope of a future when things might be better. Whether it’s Marvel’s Black Panther comic books or the futuristic aesthetic of Janelle Monáe and her music, Afrofuturism sets a utopian horizon that allows one to find hope in the present. Utopia then is not necessarily about the endpoint, though it does vital work paving a hopeful path to a ‘better’ that lies in the future. By way of solution, utopianism offers a politics that moves away from a fixation on what is already (or yet to be) lost, instead asking how much more we have yet to gain.

So, perhaps before utopianism is tossed out the window, we might consider how much utopia can still offer us, now more than ever. Utopianism has an eye on a ‘horizon’ that constantly remains ahead, abundant with possibility. Utopia must be re-articulated not as the destination of a perfect society, but as the toolkit we wield on the journey to a better one. As we engage in everyday political thought, employing both a grounded critique of the present and a creative contemplation of the future is invaluable. If there is one thing utopian thinking might offer us, it is the hope that the social ills of today need not be the social ills of forever. Utopia might be the horizon of light at the end of the tunnel.