Over the past decade, and especially since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, more and more Americans have reoriented their lives in accordance with Stoicism. Stoicism sought what the Greeks called eudaimonia: wellness of being, or ‘the good life’. These philosophies taught that the good life was attainable through concrete exercises, performed in accordance with the correct philosophical worldview. The Stoics taught that, by practising their set of exercises, practitioners could learn to see the world from a universal perspective, understand their place in it, and freely and dispassionately assent to carry out the duties imposed upon them by fate. Stoic happiness comes from wisdom, justice, courage and moderation – all states of the individual soul or psyche, and therefore under our control. Everything else is neither good, nor bad. While these beliefs about daily life rested on a foundation of physical and metaphysical theory, the attraction of Stoicism was, and is, in the therapeutic element of its exercises: cognitive behavioural therapy, or Buddhism, for guys in togas.

Despite the benefits of Stoic spiritual exercise, you should not become a stoic. Stoic exercises, and the wise sayings that can be so appealing in moments of trouble, conceal a pernicious philosophy. Stoicism may seem a solution to many of our individual problems, but a society that is run by stoics, or filled with stoics, is a worse society for us to live in. While the stoic individual may feel less pain, that is because they have become dulled to, and accept, the injustices of the world.

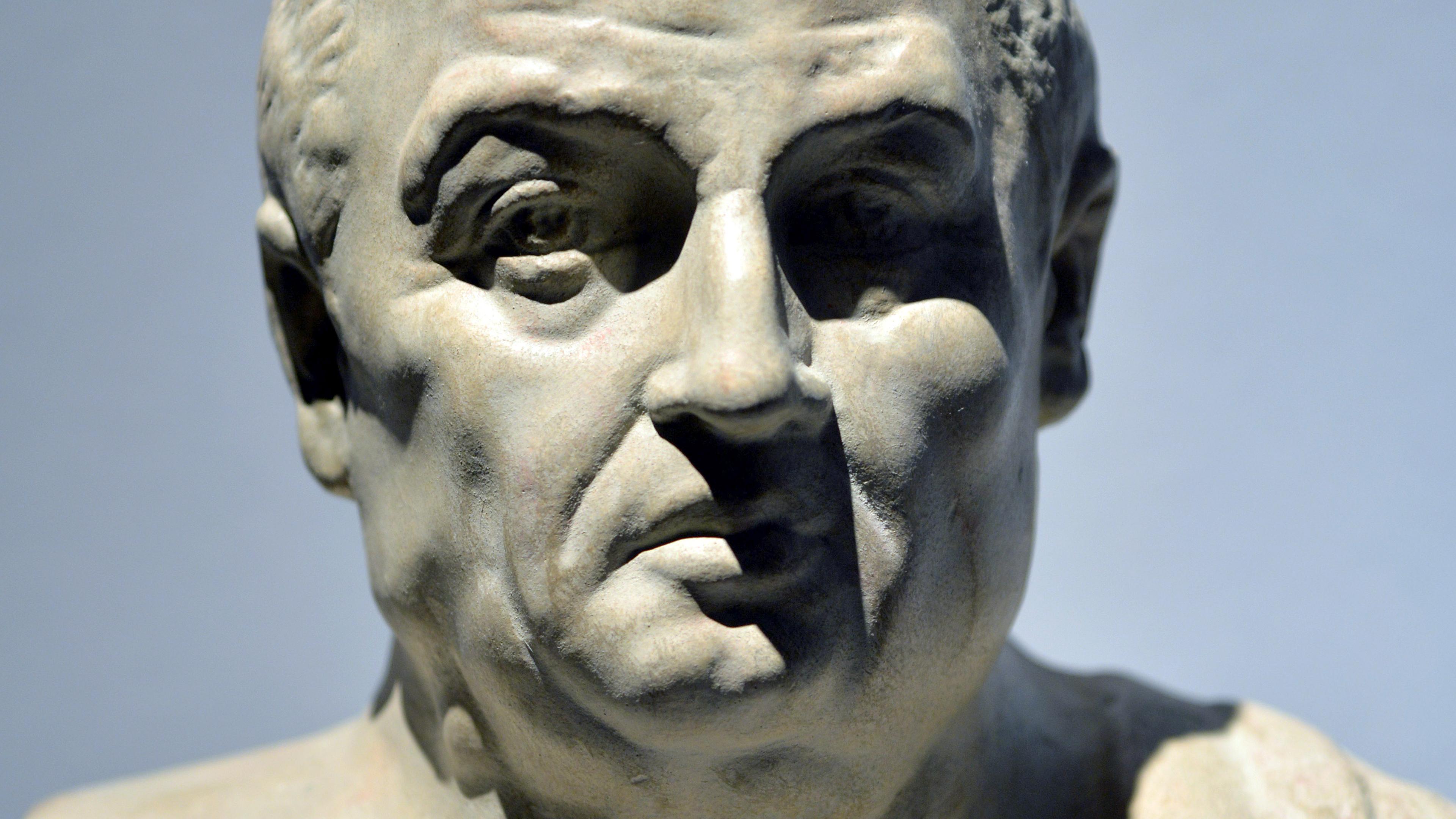

The stoicism that has become popular today draws on Seneca, Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, three men living during the Roman Empire, who were concerned with ethics – that is, how we go about our daily lives. Seneca, a wealthy courtier who wrote plays and moral treatises, was the tutor to an emperor (a bad one: Nero, whom legend has condemned for fiddling while Rome burned). Epictetus, born in Asia Minor, came to the imperial capital as a slave. He was educated by his wealthy owner and eventually freed. Epictetus became a teacher, first at Rome and then in Greece, and one of his students published his lecture notes. Aurelius – well, he was the Roman emperor. He is said to have ruled justly, and dealt with long, persistent wars against barbarian tribes and a long, persistent pandemic, which sapped the empire’s moral and demographic strength. A self-consciously philosophical emperor, he practised Stoic spiritual exercises, and his exercise book, known as the Meditations, survives.

Seneca, Epictetus and Aurelius all lived centuries after the Stoic movement appeared. They represent a Stoicism that had been adopted as something like the official state philosophy of the Roman governing class. The flowering of Roman Stoicism corresponded with the period in which Rome’s nominally republican form of government (a senate, popular assemblies, elections, bribery scandals) ceded to a hereditary monarchy (rule by an emperor, capricious executions). As the republic collapsed, Stoicism became the philosophy of choice for Roman elites who had lost their roles in governing the republic and could govern only the ‘inner empire’ of their souls. Roman Stoicism, linked to the shift from a republic to monarchy, is in essence a philosophy of collaborators.

People say Seneca was Nero’s tutor, as if their relationship ended when the future emperor was just a boy. But Seneca worked for Nero long into his reign, and wrote speeches for him, including the one justifying the murder of Nero’s own mother. Ultimately, Seneca was accused (falsely, we think) of conspiracy. Ordered to take his own life, he demonstrated his ultimate ‘freedom’ by obeying. Seneca freely assented to his place in the world and embraced his fate. He was neither critic nor resistor. A Stoicism that glorifies Seneca glorifies the elite collaborator – willing to kill himself rather than rock the boat – rather than those who actually conspired to remove a dangerous leader.

Epictetus, unlike the wealthy but ultimately powerless Seneca, was not a displaced elite. He was a displaced person, enslaved as a child and taken to the Roman metropole. The writings attributed to him are some of the very few words of the enslaved that survive from the ancient world. Many therefore presume that Epictetus’ enslaved status makes him a voice of the subaltern. And it is true that he critiques the powerful. Indeed, he will accuse his rich pupils of themselves being enslaved. ‘You are no different from those who have been sold three times,’ he tells a former consul, who is a slave to his ambition. We are all slaves, Epictetus says. But, despite Epictetus’ subaltern status and his critique of the elite, he does not make an emancipatory argument; rather, he reveals to us that Stoicism cares nothing about slavery. Stoicism responds to real injustices such as slavery by pointing out that we are all at least metaphorically enslaved. In doing so, it elides and occludes the real horrors of a slave society – or of our own wildly unequal world.

Aurelius is the final source we have for Roman ethical Stoicism. He was the Roman emperor from 161-180 CE, at the end of what Edward Gibbon called the ‘most happy and prosperous’ period of human history. Aurelius was not an original thinker or theorist, but rather a Stoic practitioner, whose book of philosophical exercises survives. The obsession with Aurelius among many contemporary stoics suggests it is his power, just as much as his ideas, that draws readers to his text. These readers exalt Aurelius as an emperor running his empire and a general dutifully journalling as his victorious army clears the dead from the field. Stoicism takes Aurelius as the avatar of enlightened, world-shaping power, read by presidents, Marines and aspiring tech disrupters.

The attention to Aurelius as emperor comes at the price of overlooking the young Marcus, a lover writing erotic letters to his teacher, the African orator Fronto: ‘I’m often angry with you when you’re away, and I get so mad, because you won’t let me love you as I want to, that is, you won’t let my spirit follow the love of you up to its highest peak.’ Over the course of their correspondence, Aurelius leaves rhetoric behind for Stoicism, and, as his training progresses, the young boy so madly in love is lost. When Aurelius, late in life, listed his mentors, Fronto barely registered. Aurelius adopted Stoicism and duty, abandoning his early passion. By exalting Aurelius the resolute commander rather than Marcus the enraptured lover, Stoicism rejects love and its vulnerability in favour of power.

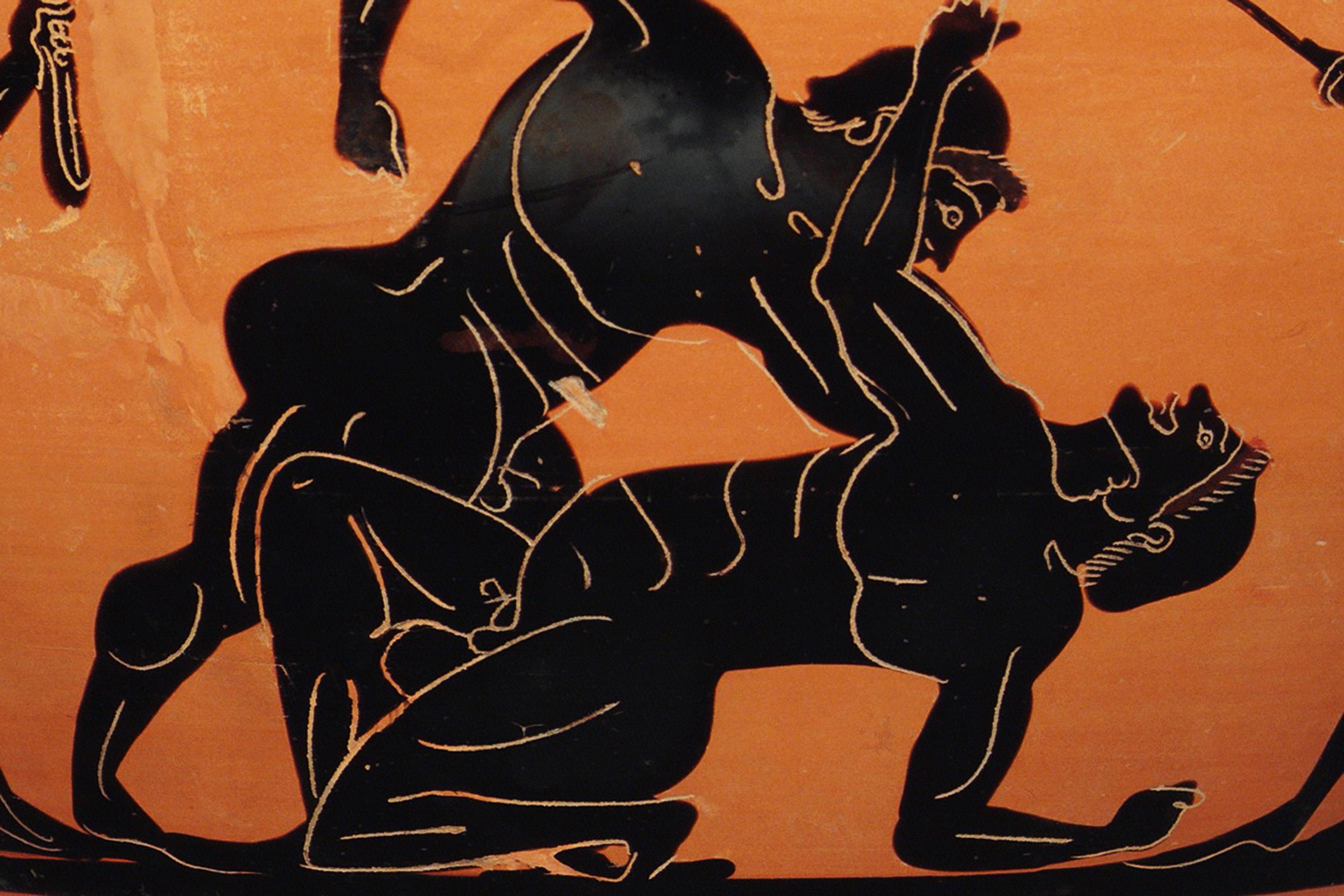

Seneca’s essay De Constantia shows us the Stoic sage – the ideal to which practitioners aspire – in action. A Greek warlord sacks a city. A philosopher is brought to him as a captive. The philosopher tells the conqueror that he has lost nothing, as ‘he had with him his true possessions, upon which no hand can be laid, while the property that was being scattered and pillaged and plundered he counted not his own, but the adventitious things that follow the beck of Fortune.’ He still had his wisdom, sense of justice, virtue, moderation. Everything ostensibly lost was temporary, furnished by fate for a time, and he did not mourn losing them as they were never truly his.

Seneca says that, although ‘his estate had been given up to plunder, his daughters had been outraged by the enemy, [and] his native city had passed under foreign sway,’ the philosopher ‘wrested the victory from the conqueror’:

Amid swords flashing on every side and the uproar of soldiers bent on pillage, amid flames and blood and the havoc of the smitten city, amid the crash of temples falling upon their gods, one man alone had peace.

This is a horrific passage. His daughters had been raped. His friends slaughtered. His city, destroyed. And yet the sage stands unmoved.

The world stands in the middle of a pandemic, a climate crisis, and, in many countries, our own crises of (at least quasi-) democratic self-governance. It may be tempting to embrace a philosophy that counsels us not to be sad, not to mourn the things we’ve lost, to accept all that happens as fate, and to do our duty even as the world crumbles around us. But we should not write speeches for Nero; nor should we glorify the power of the emperor. We should mourn our families when bad things happen to them, our cities when they are threatened, our houses when they burn or flood. It is not easy to feel grief, and it is tempting to seek out exercises to suppress it. But to look around the world and feel the pain of injustice, to understand and wallow in the hurt of the natural world – this is not a sign of weakness. It is a sign of humanity, and the first step towards taking action. Because if you accept your fate joyfully, as a Stoic sage should, you’ll never try to change it.