Three of the four great tragedians are Greek: Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides (Shakespeare is the fourth). Writing in the 5th century BCE, their tragedies are focused on great houses and their dynastic quarrels and ambitions. Characters are faced with external pressures from their family or society that they struggle to resolve, or they bring about their own downfall due to personal flaws. Two and half millennia later, the tragedies contain lessons that still apply to our personal lives. After all, the key question tragedy asks is ‘What should I do?’ Even those of us who are not as high-born as the tragic characters will often face similar pressures, or we can recognise their flaws in ourselves and see how they lead us to err too.

People are inherently flawed, none of us is perfect

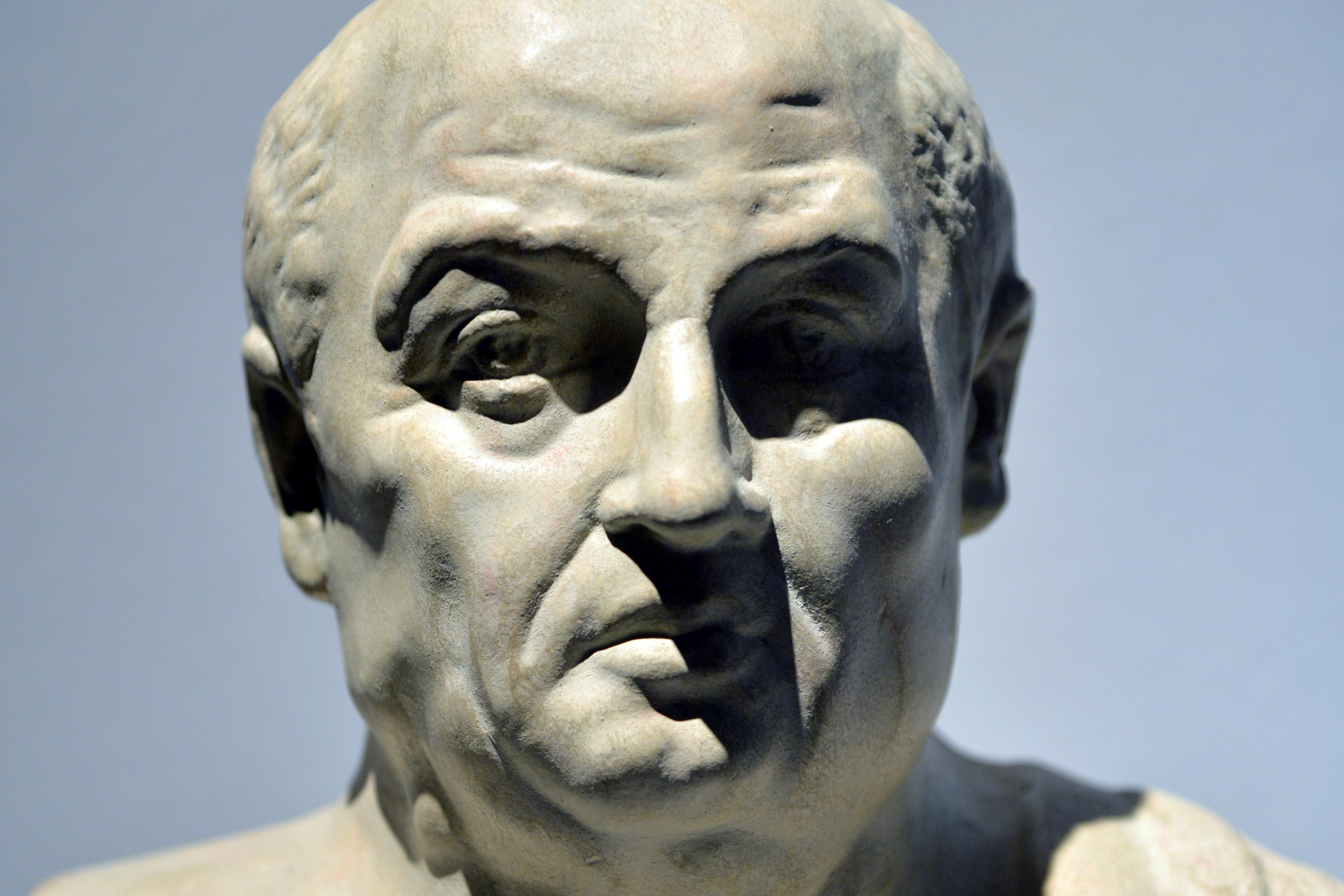

Tragedy contains the concept that Aristotle called hamartia. In Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, perhaps the greatest of all tragedies, Oedipus falls from king to exile, not due to his sinfulness, but due to an error of character that is not his fault. He makes a series of choices that are influenced by his flaws. Oedipus meets an older man who refuses to give way at a crossroads. Oedipus loses his temper and chooses to strike out, killing the man without knowing who he really is. Hamartia can be seen as a basic human vulnerability that involves us in actions that lead us to suffering. I agree with the philosopher Simon Critchley when he claims we can expand this idea of vulnerability and, as it is present in all of us, see hamartia as a basic weakness and limitedness that defines us as human beings.

When you are wronged, thinking tragically can help you: instead of focusing on the harmful act and holding whoever did it to account for the impact it had on you, try to see what they did as a manifestation of a basic weakness that they were possibly helpless to prevent or unaware of – a fundamental human weakness that you too might possess. Do this, and in the very heart of conflict, you can recognise what binds you and the other person(s), rather than what divides you.

Human experience is a complex interaction between fate and freedom

Tragedy teaches us that there is much out of our control. Mortal actions are subject to forces that transcend us. Characters in the tragedies are pawns in the petty squabbles of the gods. They attempt to defy prophecies, but events outside their control, or the unintended consequences of their actions, see the inevitable fulfilment of what is foreseen. Similarly, we live today in a supposed democratic meritocracy, yet our actions are subject to the invisible gods of market forces and algorithms. We can find ourselves pawns in the petty squabbles of autocratic leaders.

But at the same time, within the confines of fate, we are free to make choices – this is how our destiny plays out. Oedipus’ fate is not entirely decided by the choices he makes, but the interaction of forces outside of his control interacting with his choices. You can see this by looking backwards from the moment he murdered that stranger at the crossroads.

Our freedom is compromised by the weight of the past

Before Oedipus is born, a curse is laid upon Laius, his father, for violating the sacred laws of hospitality. When Oedipus is born, Laius consults an oracle who reveals that Laius ‘is doomed to perish by the hand of his own son’. Laius orders Oedipus’ murder, but instead Oedipus is left on a mountaintop, where he is rescued by a shepherd. Years later, when Oedipus has just been told by an oracle that he would kill his father and have sex with his mother, he lashes out at the crossroads and kills a stranger not realising he is his father. Unintended consequences of individual choices fulfil prophesied events.

Despite the curse and the prophecies, Oedipus’ rage gets the better of him. Fate requires Oedipus’ partially conscious complicity to bring about its truth. Similarly, our freedom is compromised by the weight of the past, which so many of us look to deny in our constant thirst for the next thing. As the author and critic Rita Felski wrote: ‘[T]he weight of what has gone before bears down ineluctably on what is yet to come.’ We are all shaped by our own pasts, our childhoods, our parents’ experiences, and collective group experiences. Tragedy teaches us that if we do not realise this and we try to disavow the past, then at best, we will be destined to repeat what has come before, and at worst, be destroyed by it.

To many moral dilemmas, there are no clear answers

Tragedy is not the triumph of evil over good, but the suffering caused by the triumph of one good over another. Tragedy is about morally defensible but incompatible goals. In Aeschylus’ Seven Against Thebes, brothers Eteocles and Polynices have killed each other in combat. Afterwards, their uncle, Creon, the new king of Thebes, declares that Eteocles will be honoured, but Polynices will be left on the battlefield and denied burial rites as a punishment for being a traitor (for attacking his brother). Creon believes this punishment is necessary for the stability of the state and avoiding future bloodshed. In an act of disobedience, Antigone declares she will bury her brother out of loyalty to her doomed blood. After burying him, she asks: ‘What shall happen to me? What shall I do?’ The chorus divides into two groups. There is no reconciliation.

Tragic thinking can help you cease to strive for the unobtainable

In our lives, the dilemmas we face, big and small, are often equally ambiguous. Trawling through the agony-aunt columns of national newspapers, you find people worrying about whether they should date a long-lost cousin, confront elderly parents on past mistreatment, or intervene in the destructive behaviour of others. There are many seeking advice on how to rectify differing sexual preferences with partners and many more asking how to balance responsibilities towards others with their own desires and ambitions. In uncertain times, conspiracies and extreme political and religious views flourish in anxious populations. All these people are seeking answers, but to many of the questions, there are no clear answers.

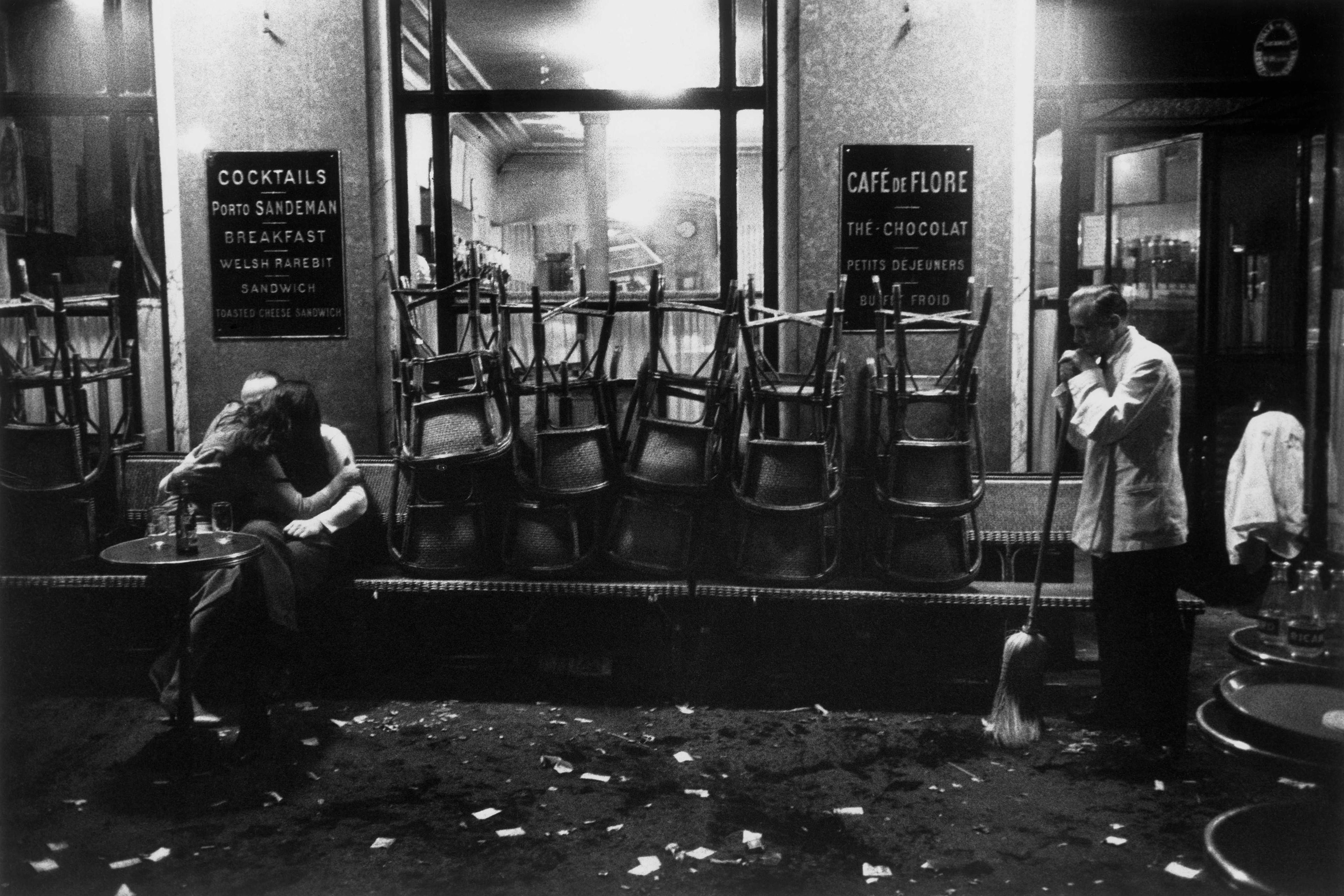

While you seek non-existent definitive answers, big and small, you could miss the wonder in the uncertain present. It is the sensation of life that you lose when you focus on some overarching purpose or commit to finding answers in ideologies and religions. Despite their beliefs in gods and the afterlife, the ancient Greeks were focused on what one does in this world, in the here and now. Tragic thinking can help you cease to strive for the unobtainable. It can also help you find resolution with others. If you view conflicts as black and white, with one side being unequivocally right and another wrong, it leaves little space for co-existence and comprise. It can blind you to the suffering of others and lead you to justify the unjustifiable. Tragic tales of past conflicts can point a way towards living together in the present.

Grief and rage are an inevitable part of life

Many of the audience members and actors at the original performances of the Athenian tragedies would have been soldier-citizens who fought in the Peloponnesian War, and this surely would have helped them appreciate the lessons of tragedy. The former war correspondent Robert Kaplan, who blames the disasters of Iraq and Afghanistan on Western policymakers’ failure to think tragically, claims that the young veterans he has met understand tragic thinking better than ‘experienced’ policymakers in Washington, who have never experienced the chaos of war.

Aeschylus had fought the Persians at Marathon, and might have fought at Salamis just eight years before his play The Persians was performed. Many of the tragedies deal with the aftermath of the legendary Trojan War and the events covered by the Iliad, the first two lines of which read: ‘Rage Goddess, sing the rage of Peleus’ son Achilles, murderous, doomed, that cost the Achaeans countless losses’. The opening of the Iliad describes Achilles’ rage at the loss of face and then the loss of his closest companion.

Blind Tiresias gives Oedipus the answers he is looking for, but Oedipus doesn’t hear and instead rages at him. Tiresias claims: ‘You blame my temper, but do not see the one which lives within you.’

Tyrannos in Sophocles’ original title, Oidipous Tyrannos, can be interpreted as ‘tyrant’. Tyrants don’t hear what is said to them, nor see what’s in front of them. Oedipus is blind with rage before he later literally blinds himself when he sees what he has done. In Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus, Oedipus blames the gods for his misfortunes, ‘raging, perhaps, against our race from ages past’. Many of us are similarly guilty. We look, but see what we want, listen, and hear only what we want. Anyone who tells us what we don’t want to hear can experience our rage.

You can create meaning by treating human life with dignity even when it is flawed

The poet Anne Carson asks and answers: ‘Why does tragedy exist? Because you are full of rage. Why are you full of rage? Because you are full of grief.’

We grieve those we’ve lost who we cared about. Over the years we will lose more. As Oedipus laments: ‘Only the gods never age … All else in the world almighty time obliterates.’ We not only grieve over the loss of those we love, but we grieve more abstract losses; time that has passed and our youth that has gone with it, our failing capabilities, our standing in our world, and the company, respect and love of others. With nostalgia, we grieve what we never had. While the pain of losing loved ones may turn to rage, the grief is evidence that their lives mattered, that all life matters.

A tragic mindset is ultimately about finding a way to release this rage without creating more grief, to deal with all our losses without hurting others. In rage, we act freely but something acts through us too, some kind of curse, the largely unconscious effect of the past on the present. In Oedipus in Colonus, Oedipus curses his son Polynices to die at his brother’s hand in battle, blaming him for not preventing his exile. Antigone asks Polynices why he seeks to dethrone his brother. He replies: ‘Exile is humiliating, and I am the elder and being mocked so brutally.’ Antigone responds: ‘Don’t you see? You carry out father’s prophecies to the finish!’ Antigone tries to break the cycle of violence. She ultimately fails. In Sophocles’ Antigone, Creon condemns her to death for burying the brother who refused to listen. Yet, when she takes her own life, she remains uncompromised, a lone ray of heroic light in Oedipus’ dark universe. According to Robert Kaplan, the tragic sensibility says that ‘there is nothing more beautiful in this world than the individual’s struggle against long odds, even as death awaits’.

Tragedy shows you that you can create meaning by treating human life with dignity even when it is flawed and even when disaster befalls it. Dignity is magnified when you do not seek to blame others for what you lose and stand tall to face the coming storm, aware that the precariousness and fragility of life give it its majestic, precious urgency.

Carry on anyway

The tragedies describe a world in constant conflict defined by capriciousness, ambiguity, uncertainty and unknowability, where people are often swept along by forces they interact with but don’t fully comprehend. This is our world too. In The Greek Way (1930), the classicist Edith Hamilton claimed the lyric verses of the tragedies contain the beauty of intolerable truths, truths that are too much to bear. Yet, to think tragically is to recognise the need to try to break these cycles of grief and rage – those that we experience in our personal lives and that play out today on a grander scale in Gaza, Israel, Ukraine, Ethiopia and Yemen. It is to try and make the intolerable tolerable. Sometimes we will be successful, even if only temporarily. Grace in a human being means embracing the poetic truths revealed in the tragedies and, like Antigone, carrying on anyway, no matter how successful you might be.