Fear has taken on a new role for many people in the past year – suddenly, a routine grocery run is a vector for a terrifying disease, and we’ve adapted to a ‘new normal’ in which we can’t connect with others like usual without risking either of our lives. Eventually, of course, we’ll reintegrate to another new normal, and we’ll have to struggle through a new set of fears.

This reoxidation into humanity will shine a light on the responses of panic and fear that are all too familiar to autistic individuals. Now, even the most extroverted of us are embodying anxiety when walking down seldom-occupied streets. How are we going to cope with the sudden influx of traffic, crowds and sensory overloads that lifting lockdowns will entail? Isolation has given us a renewed sensitivity to the world, much like the fresh ears of a child, where every new stimulus can invoke a fear. With our familiar normal redefined as a danger, meltdowns are inevitable when we return. But I have your back on this one. Since I’m autistic, with an innate fear of crowds, I have a mechanism to help you.

For all of us, fear of re-entry is compounded by fears of climate collapse, political uncertainty and our own personal anxieties. Sometimes, there’s too much information to process, and guilt at the lack of opportunity to act. This leaves many of us sitting at home with our thoughts, like being in a pressure cooker.

These are the perfect ingredients for my experiment, in which I become a prism for fear.

Fear is something we all have, and it’s essential to our survival as a species. Without fear, we’d have no scepticism, no caution, no checks and balances on our impulses. But the opposite is also true. When all we can feel is fear, it becomes paralysing, leaving us unable to think clearly or make decisions at all. We risk being controlled by the things that make us afraid, rather than taking control of them. We get stuck.

The bittersweet gem of being neurodivergent is that I have had (and still have) my fair share of meltdowns – thanks to weird smells, sounds, sensory pressures and social abstractions. I have plenty of experience with the obvious anxiety triggers such as sudden loud noises, as well as fears whose origin even now I struggle to understand: the colour orange used to repulse me so much that I avoided it like a toxic substance. This is part of how autism spectrum disorder (ASD) works. It creates instinctive and repulsive fears that can’t be explained, but must be obeyed.

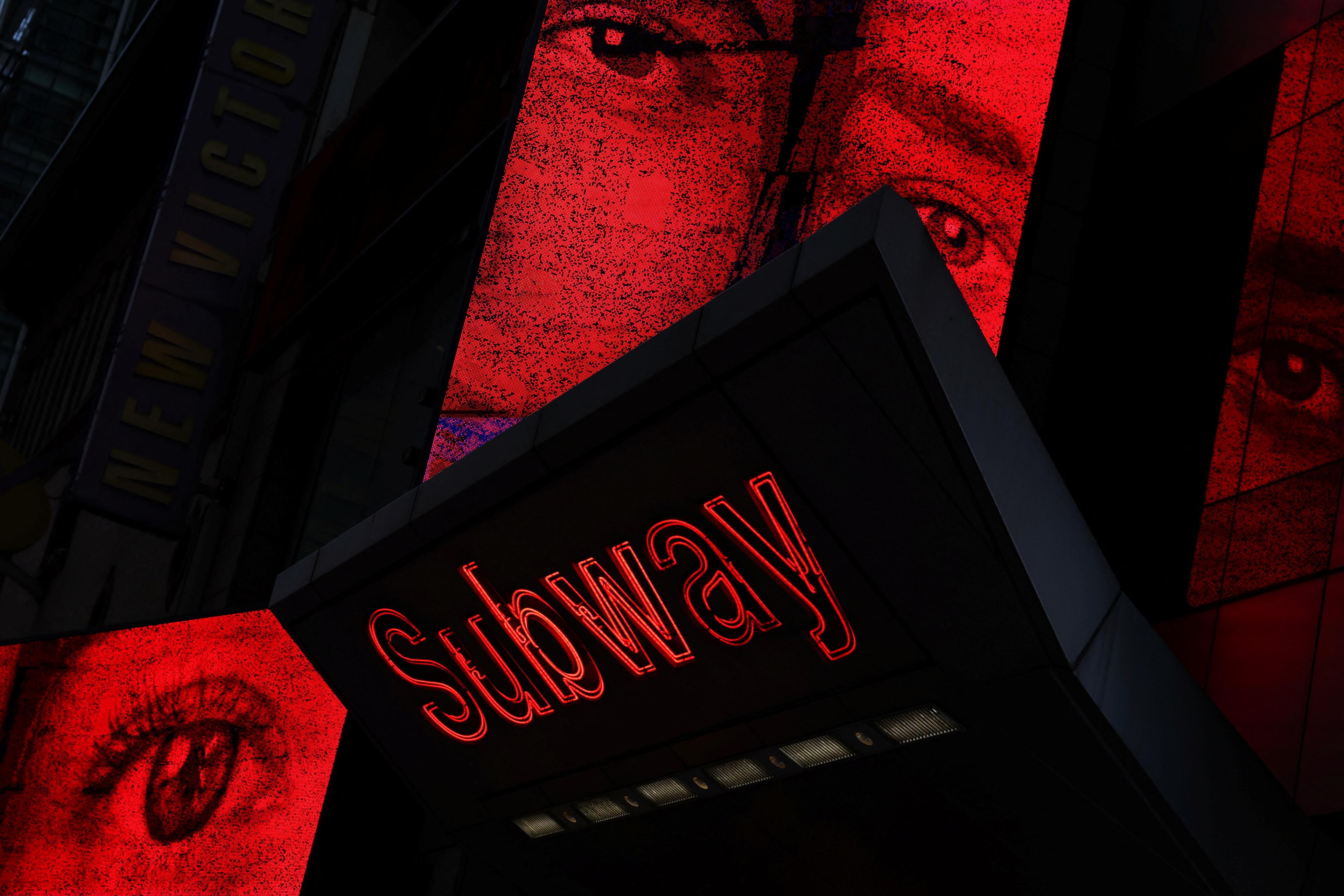

With Asperger’s syndrome – another name for ASD – there are moments when all your thoughts and fears rush onto you like a beam of blinding light. You experience everything all at once and have no inherent ability to separate the different emotions, anxieties, impulses and stimuli. In school, a routine fire alarm would send my senses running red-hot, the noise reverberating through my entire body. The feeling was one of total physical dread. While the other students would form neat ranks like soldiers, I always had to run as far and as fast away from the noise as possible. I would have to retreat to darkened rooms and wear noise-cancelling headphones or, quite possibly, head for the safe canopy under my desk. This was, and still is, my survival method. But it’s no way to live.

Because I have no built-in, unconscious filter, I had to create my own: one that would allow me to cope with fear and function alongside it. And, even though fear felt like a blinding light, my study of photonics (photons being the quantum particles that make up light) helped me to realise that fear could be broken apart in the same way that a beam of light can be refracted, revealing its many different colours and frequencies. Our fears, which are never as singular or overwhelming as they sometimes feel, can be treated in exactly the same way.

Has anyone ever told you in moments of fear to slow down, or pause for breath? Well, that’s exactly what refraction achieves. When light passes from one substance to another, it will change speed. Because light travels less quickly through glass or water than through air (both having a higher refractive index), the wave of light will slow down. In the classic prism example, the light then disperses into its seven visible wavelengths in all their vivid splendour: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet (plus the invisible: infrared and ultraviolet).

By slowing down the speed of the light wave, we’re able to see it differently: in its full glory and many colours. The prism effect gives us a new perspective, turning something that was singular and dazzling into a spectrum that’s much clearer, and even more wondrous. If we want to understand our fears properly, we need to do the exact same thing: look at them through a new lens, so we can see them differently, and change how we respond accordingly.

Refraction through a prism happens because light doesn’t travel in straight lines, but in waves that oscillate and undulate, dependent on their energetic differences at any given time. This applies to light waves, sound waves, radio waves, X-rays and microwaves. Every wave, whether it’s the one that allows a fishing boat to tune its long-wave radio, or the one you use to cook a ready meal, has its own frequency. A high-frequency wave has tall peaks that occur close together, like a particularly spiky Toblerone bar. Its low-frequency cousin unwinds more gently, similar in form to a loosely coiled snake.

The higher the frequency, the more energy is carried, but the less distance it can travel in a prism since it interacts with the atoms contained within, dissipating energy. When light refracts through a prism, we see the different colours because the glass has slowed down the waves to a speed that falls on the visible spectrum (waves that can be seen by the human eye). The transparency of the spectrum expands its meaning to metaphor here, since, to deal with fear, we must let in the ‘light’, or stimuli, which can feel as painful as staring straight into the Sun.

For both light and fear, an understanding of wavelengths is critical. That initial sense of fear, that blinding white light, is not singular but actually contains many different emotions, triggers and root causes. And these elements aren’t all equal: like the different colours in light, our fears and anxieties have their own wavelengths, with varying intensity. Some (for me, hearing a loud noise in the street) will flare vividly over a short distance, while others (such as my fear of having to look people in the eye) will maintain a less insistent, but more sustained drumbeat in the head.

The most powerful, insistent emotions are like high-frequency violets – intense and choppy – while the nagging feelings are more laid-back, low-frequency and long-lasting reds. And, just as happens at sea, different waves combine to create a tsunami of fear that you’re powerless to prevent from crashing over you. This was my biggest breakthrough in managing the fears that threatened to derail me. Anxiety is not a single, solid state resting in our heads, but a fluid entity that contains a multitude of different components. The concept of refraction can help us separate these, untangling the different things that make us afraid, distinguishing between the high- and low-frequency triggers, and ultimately finding ways to manage them.

When I feel a panic coming on, I use the prism effect to diagnose the situation and try to avoid a full-on meltdown. Is it a high-frequency wave, a sensory trigger in my immediate surroundings, like someone accidentally brushing past me, shouting loudly or giggling at a high pitch? Or is it one of the low-frequency, constant thoughts that occupy me: fears about the future, getting ill or whether my itchy jumper is going to give me psoriasis?

For example, if someone asks me to look them in the eye, I’ll immediately feel that burst of short-wave, white-light fear. But, using the prism approach, I can separate out some of the waves within that white light: the longest, reddest one that represents a fundamental fear of human contact from the more immediate, violet wave that’s my fear of someone’s eyes burning through my well-practised exterior and revealing my anxious core. Once these threads have been identified, I can start to rationalise with myself: yes, I don’t relish this kind of human contact, but I know from experience that it won’t actually hurt me. And no, this person probably isn’t trying to look me in the eye to uncover anything: they’re just trying to have a conversation. They’re not going to find out simply by looking at me how much I’ve learned about them just through observation. This speed profile might be different for you, but knowing which fears strike which chord of your mind is one of the greatest steps in processing what affects you, helping you make your next move.

Having tussled with fear and anxiety throughout my life, I eventually came to an important realisation: instead of being one of my greatest liabilities, anxiety is actually one of my most important strengths. It allows me to accelerate possible outcomes in my head, reaching conclusions much more quickly (out of necessity, because there is so much data to process).

When it comes to fear, we all have our own particular anxieties. I’m not afraid of the things that you probably are, but I can be terrified by things you wouldn’t even notice. Lacking the typical filters, I’m both overexposed to mundane things, and unaware of the many social conventions and norms that I haven’t carefully taught myself through experience. I might get completely thrown off by a change of routine in a gym class, but stay very calm if I learn that a family member or friend has cancer (which makes me a bad exercise partner, but an excellent listener and therapist). When you actually have to live with #nofilter, it can be a disorientating experience, but it’s also a true representation of the strengths of neurodiversity, and the contrasting skills it allows us to bring to the table.

I know there’ll never be a day of my life when I don’t feel afraid. But I also know that it’s thanks to fear that I really feel alive. Fear isn’t something we need to ‘shine a light on’. It is the light, one that we can all learn better how to live with, and even benefit from. It’s why I see the fear that my ASD instils in me not as a problem to solve, but as a blinding privilege to take advantage of.

Excerpted with permission from the book An Outsider’s Guide to Humans (2020) by Camilla Pang (Viking).