When OpenAI released ChatGPT in 2022, many people were impressed and even a little scared. ‘We have summoned an alien intelligence,’ the author Yuval Noah Harari wrote, with colleagues, in The New York Times. ‘We don’t know much about it, except that it is extremely powerful and offers us bedazzling gifts but could also hack the foundations of our civilization.’

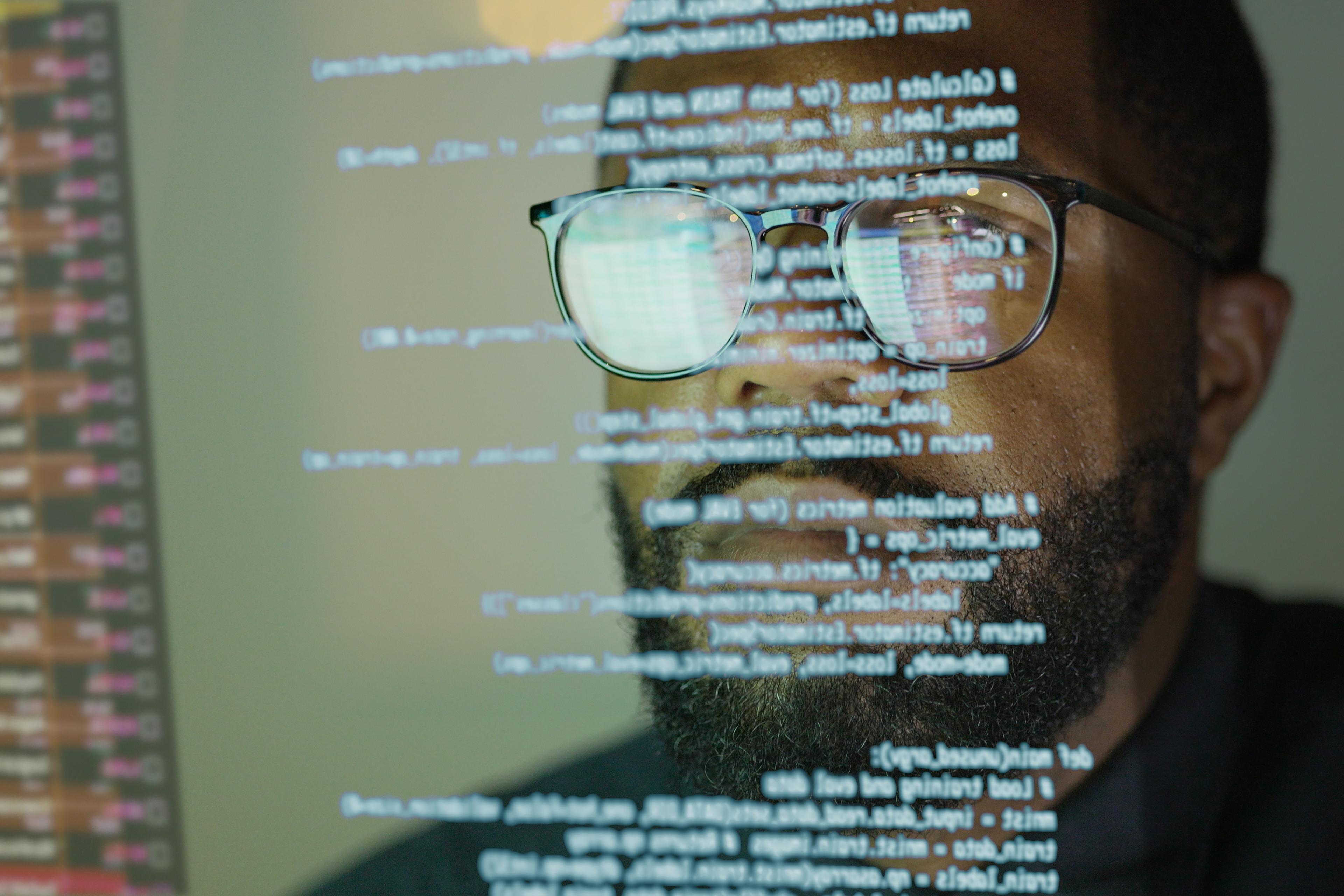

ChatGPT is a large language model trained on terabytes of human-written text, from books to Reddit, Wikipedia and Twitter. But despite the hype or concern around this form of artificial intelligence (AI) becoming sentient, for now at least, humans – even children as young as three – still have the upper hand when it comes to innovating. That’s according to Eunice Yiu, a psychology graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley and the first author of a recent study in Perspectives on Psychological Science that pitted children against AI in a variety of tasks.

Yiu is part of Alison Gopnik’s research lab at UC Berkeley, where they study how children learn, and if children and AI systems learn in similar or different ways. ‘A lot of people like to think that large language models are these intelligent agents like people,’ Yiu says. ‘But we think this is not the right framing.’

Trained on human-generated data, large language models are very adept at noticing patterns in that data. But learning from existing written material – even massive quantities of it – might not be enough for AI to come up with solutions to problems that they’ve never encountered before, something that children can do.

Yiu and her colleagues showed this is in a series of experiments. In one, they gave children (aged three to seven), adults, and five large language model AI systems (including OpenAI’s GPT-4, Anthropic’s Claude and Google’s FLAN-T5) descriptions of everyday objects, such as a ruler, a compass (the drawing and measurement tool) and a teapot. Then, they asked each group to match up the objects that were most similar to each other: the compass should be matched with the ruler, not a teapot, for instance. The majority of children, adults and AI systems could accomplish this. The AI knew which ones went together having been trained on descriptions of the objects.

But in the next task, the researchers gave human children, adults and AI some problems that could be solved only through innovation – not based on existing knowledge. For example, Yiu and her team asked the humans and AI how they might draw a circle without using the compass. The team offered three options of alternative tools to use: a ruler, a teapot or a stove.

The ruler is conceptually similar to the compass because they’re both tools of measurement. But, of course, it is useless for drawing a circle. On the other hand, you could draw a circle with a teapot by tracing around its circular shape. However, because a teapot seems unrelated to the task of drawing a circle, it requires some novel thinking to realise it’s the optimal tool in this situation.

In this task, 85 per cent of children and 95 per cent of adults picked the teapot, rather than the ruler, to draw a circle. (The stove was irrelevant, and included as a control.) In contrast, the five AI models struggled on the innovation task; they often chose the ruler to draw the circle. The worst-performing model, Text-davinci-003 (a recent version of ChatGPT), picked the correct answer around 8 per cent of the time, and the best model still did it only 76 per cent of the time.

‘We’re not saying that large language models are completely not capable of anything, they’re really good at imitation,’ Yiu says. We might think of AI systems as closer to other cultural technologies such as writing, libraries, the internet or language – powerful and useful, but not innovative on their own.

This still allows them to do impressive things that feel like intelligence to us. On a long car ride, the New Yorker staff writer Andrew Marantz and his wife prompted ChatGPT to generate a story about the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles to keep their children entertained. ‘We didn’t need to tell it the names of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, or which weapons they used, or how they felt about anchovies on their pizza,’ he wrote. ‘More impressive, we didn’t need to tell it what a story was, or what kind of conflict a child might find narratively satisfying.’

Although coming up with a new Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles story might seem like a form of creative thinking or innovation, in fact the AI is doing this based on existing human-generated information. True cultural evolution requires innovation too, Yiu says.

Imitation of the kind that large language model-based AI is capable of is an important part of human cognition: it allows us to learn from each other, and pass along skills to family members or one’s community. But it’s the human capability for innovation that allows us to generate new solutions to problems, and to adapt to changing environments or circumstances. ‘Innovation challenges the status quo and questions the conventional wisdom that is the training corpus for AI systems,’ Yiu and her colleagues wrote in their paper.

Learning about how AI differs from human children’s learning could be a way to develop new AI systems one day. Gopnik, the senior author on the paper, has done just this through collaborations with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in a project called Model-Building, Exploratory, Social Learning System (MESS), which seeks to design models that incorporate how babies learn into AI.

‘It cannot go out there to make new observations, interact with the world and make new thoughts’

Babies learn complex concepts about the world through messy unsupervised data sets. They can learn about categories from a small number of examples. For instance, after flipping through a few pages of a picture book, they can distinguish between cats, dogs, jaguars, rhinos and unicorns. ‘Parents may occasionally tell a baby the name of the animal they’re seeing or say “good job” when they perform a specific task,’ wrote Gopnik in The Wall Street Journal about the MESS project. ‘But parents are mostly just trying to keep their children alive and out of trouble. Most of a baby’s learning is spontaneous and self-motivated.’ Perhaps Alan Turing was on to something when he suggested that, instead of making a computer program to simulate an adult’s mind, ‘why not rather try to produce one which simulates the child’s?’

‘A child can learn from little things, and then generalise into bigger contexts, and this may be a way for us to build smarter AI systems,’ Yiu says.

For now, if you want ChatGPT to talk like a child or imitate a famous person, it can do that. But there are limits. ‘It cannot go out there to make new observations, interact with the world and make new thoughts, theories and predictions,’ Yiu says.

ChatGPT agrees. When I asked it why large language models aren’t as good at innovating, this was the response:

Language models like me are great at processing and generating text based on patterns, but we don’t really understand things deeply, get creative, or experience the world like young kids do. Children aged 3 to 7 learn through play, emotions, and hands-on experiences, which gives them a unique edge in innovation that current language models lack.