When researching other people’s lives, authors often visit archives to dig into the ephemera that made that person who they were. But when exploring our own lives, we seem to forget that we have our own personal archives, including old journals, email, text threads and voice memos.

Lately, I’ve been dipping into my personal archives – specifically, my old journals – to reacquaint myself with the person I was 20 years ago, doing remote fieldwork in the Canadian Arctic for eight weeks each summer. I’m writing a book, you see, about my experiences as a field scientist, and though my memories of that time seem strong, I’m still surprised by some of what appears in my journals. For example, I didn’t remember arriving in the field as early as I did one year, or the level of frustration I had when some of my equipment didn’t work. My journals bring these events back to me, in full colour and precise detail, allowing me to add lyrical descriptions and scenes to my book.

Research shows that keeping a journal is a way to be more mindful, to really think about what you’re experiencing and how it affects you and others. More specifically, journaling can also improve your communication skills and sharpen your memory. Studies suggest that if, when ill, you write about stressful events and reflect on them (reflection is key), you can improve your health outcomes. Writing in a journal is also a way to get better sleep and boost your self-confidence.

I agree with the American writer Joan Didion, who said in ‘On Keeping a Notebook’ (1966):

We are not talking here about the kind of notebook that is patently for public consumption … we are talking about something private, about bits of the mind’s string too short to use, an indiscriminate and erratic assemblage with meaning only for its maker.

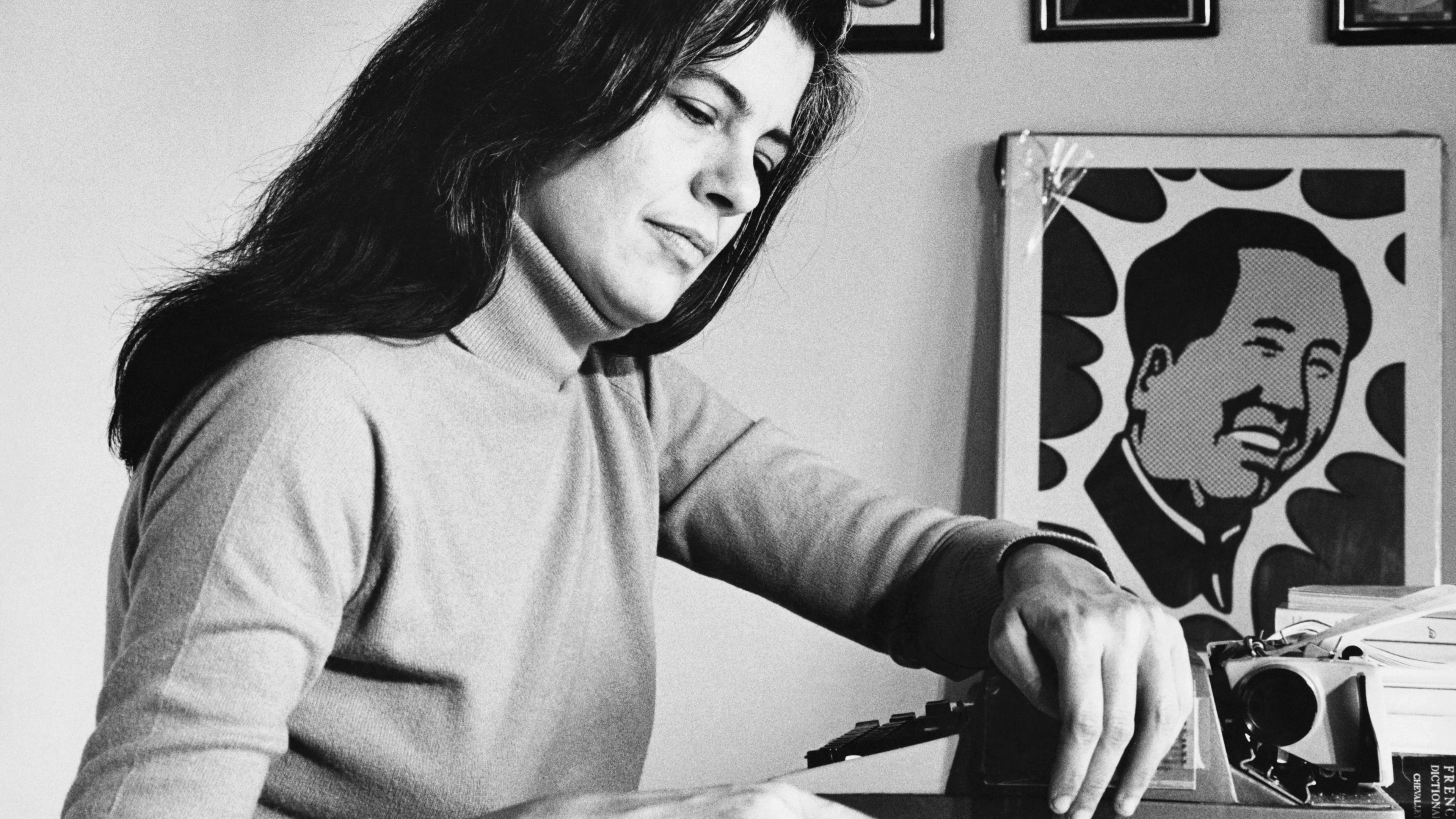

And as another American writer, Susan Sontag, said in ‘On Keeping a Journal’ (1957):

In the journal I do not just express myself more openly than I could do to any person; I create myself. The journal is a vehicle for my sense of selfhood. It represents me as emotionally and spiritually independent.

Didion and Sontag saw journals as a respite from the everyday world, a place to revel in and reveal oneself – on the page, instead of in public.

Woolf’s journals are considered not just a window inside her mind, but also ‘a remarkable social document’

For some reason, I’m often reluctant to dig into my personal archive. The themes are often repetitive: the joys of pond hockey, the importance of being myself, the admonition to exercise more or to make a schedule and stick to it. But in between are gems: short stories begun but not finished. Essay fragments replete with stunning detail and vivid characters, waiting to be brought to life. Insights into life that I forgot I ever had, that help me with my current life situations in ways I never thought possible. For example, my journals warned me regularly against becoming a science professor, but I ignored them and ended up falling out of academia due to illness. What if I had heeded my own advice?

Though they weren’t originally intended to be read by others, some writers’ journals have been published posthumously for public consumption, including those of Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, Franz Kafka and others. Readers snap up these books eagerly, hoping to find insights into the writing life, a sort of how-to manual for becoming a good writer. Though, as Didion wrote, ‘your notebook will never help me, nor mine you’. In many cases, however, published diaries show an obvious through-line of how the author became the writer we know. For example, Woolf started journaling at the age of 14, and wrote 38 notebooks from 1897 to 1941. Her journals are considered not just a window inside her mind, but also ‘a remarkable social document’. They feed directly into Woolf’s writing; in 1919, she herself said that ‘the habit of writing thus for my own eye only is good practice. It loosens the ligaments.’

Plath’s diaries cover the 13 years before she died, and are filled with musings on writing and the details of her everyday life. One Goodreads reviewer said they have to take a break from reading them because Plath’s ‘feelings were so vivid you feel like an intruder’. Kafka kept a diary from 1910 to 1923, ending just a year before his death. There is a Twitter account called @Franz_K_Diaries that Tweets daily excerpts from his journals, giving readers insight into the depressed and ill writer’s life. Some of his entries are remarkably short, reading: ‘July 1, 1914: “Too tired.”… September 22, 1917: “Nothing.”’

Other writers have published their journals as part of their oeuvre, like May Sarton’s Journal of a Solitude (1973) and Dara McAnulty’s Diary of a Young Naturalist (2020). In these cases, the author has the ability to edit out details they don’t want to share with readers, something Leonard Woolf took offence to in his foreword to his wife’s journals. He argued that taking out specific details could unbalance the document: ‘The omissions almost always distort or conceal the true character of the diarist or letter-writer …’ Sarton writes about gardening, the weather, writing, and living alone, all of which documents the evolution of her art and spirituality. An example of her insights relates to small talk, which she can’t abide, as ‘Time wasted is poison.’ McAnulty, on the other hand, writes about the natural world and his relation to it, as well as his autism and how it sets him apart from others. His book in particular focuses on ideas and big events – the mundane, everyday aspects of life are much less prominent than they are in diaries published posthumously.

So how do you start writing a diary? First, consider your goal in doing so. Do you want to compile daily events, or do you want to analyse those events through a personal lens? Do you want to practise writing, or do you want to clear your mind before you sit down to write something more polished? Do you want to publish your journal, or is it solely for your own consumption? Do you want something that you can return to and remember your thoughts about specific events? Figuring out what you want out of your journal is a critical first step in driving the rest of your journal decisions.

Think about the length of time you can allot to journaling, and at what time of day. Can you fit in 15 minutes, or do you have an entire hour free? Does morning or evening work best, both with your schedule and your mindset? Do you have to get up early and journal for half an hour before the house comes to life around you? Or do you need to go to a busy coffee shop and write for an hour? Some writers advise that you write at the same time and place every day; for example, Julia Cameron in The Artist’s Way (1992), suggests writing ‘morning pages’, which are three pages done every morning as soon as you get up. But we all have our own schedules and can’t always find the ‘ideal’ time to journal – we just have to pick a time that works, and stick with it. Alternatively, you may find that you can only snatch small moments during the day to journal, moments that change as your schedule changes. But every little bit counts.

You may surprise yourself, writing yourself into being like Sontag, or finding meaning in your life like Didion

Now consider what you’ll write about. If you’ve decided that you want to practise writing, maybe you’ll give yourself writing prompts that free you to write in your journal, for no one’s eyes but your own. If you want a compilation of daily events, you may sit down after dinner or before bed and list off what happened that day. If you want to clear your mind, you can let the words flow from your pen or keyboard like a stream-of-consciousness document, that breathes out all of the competing narratives in your head and allows you to breathe in the clarity required to do your ‘real’ writing. Or perhaps, like Kafka, you might write a few words that sum up the zeitgeist of the day that has just passed, a two-sentence summary of what that day brought you and made you think about.

Some argue that even the vessel you choose to hold your thoughts is significant. Will you write on the computer, with a new document for each day or a running document for the year? Or will you write in a cheap, lined, spiral notebook that can be found at your nearest dollar store, or in a more dashing Moleskine notebook? Perhaps you prefer a notebook bound in leather, or one in diary format with dates on each page.

In the end, however, all these questions are incidental to the main goal: to journal, write in a notebook, or keep a diary. Select your favourite writing tools, sit down and write, and see what comes out. You may surprise yourself, writing yourself into being like Sontag, or finding meaning in your life like Didion. Or recording memories for a later, more formal work, like me. All that matters is that you take time on the page to sort out the strands that make life interesting, that hold your place in that life. To figure out who you are, and what matters to you. To make your way in the world, one sentence at a time.