When does a person become an adult? Is it simply a matter of turning the legal age of adulthood (18, in many societies)? Or is true adultness signified by reaching a point along some imagined pathway, such as getting a full-time job, paying for your own expenses, getting married or having children? In many Western societies, adulthood has traditionally been defined based on social milestones such as marriage and parenthood. These indicators of ‘settling down’ were especially common in previous generations, when paths to adulthood were relatively uniform and young people frequently obtained a stable job, married and had children in their early 20s. But in today’s world, pathways into adulthood tend to be longer and more varied.

Adults in much of the world are now spending more time in education, are more likely to struggle to achieve financial independence and home ownership, and are more likely to delay, or forgo, marriage and parenthood compared with previous generations. For example, the yearly number of opposite-sex marriages occurring in England and Wales has decreased by more than half since 1972, and the average age of first-time marriage is now in the early 30s. Likewise, the average age of first-time mothers in the UK has risen from 26 in the 1970s to nearly 31 in 2021. Similar trends have been observed in many other countries, such as the United States, Australia, Japan and Chile. Paths to adulthood have changed significantly over the past six decades, yet some psychological models of lifespan development still measure adulthood according to social milestones such as these.

Given the historical changes in the relevance of traditional ‘adult’ social roles for modern adulthood, Sophie von Stumm and I set out to investigate how people today define and think about adulthood, including their own. In our recent study, we focused on the UK (where we both live), surveying 722 residents who ranged in age from 18 to 77. Our study had several main aims. One was to assess how ‘adult’ our participants felt, and how that related to their ages and life circumstances. To find this out, we asked them how much they agreed with statements such as ‘I feel like an adult’, ‘Other people consider me an adult’, and ‘I think of myself as a grown-up person.’ Another aim was to gauge overall attitudes toward adulthood – how positive or negative participants felt about it.

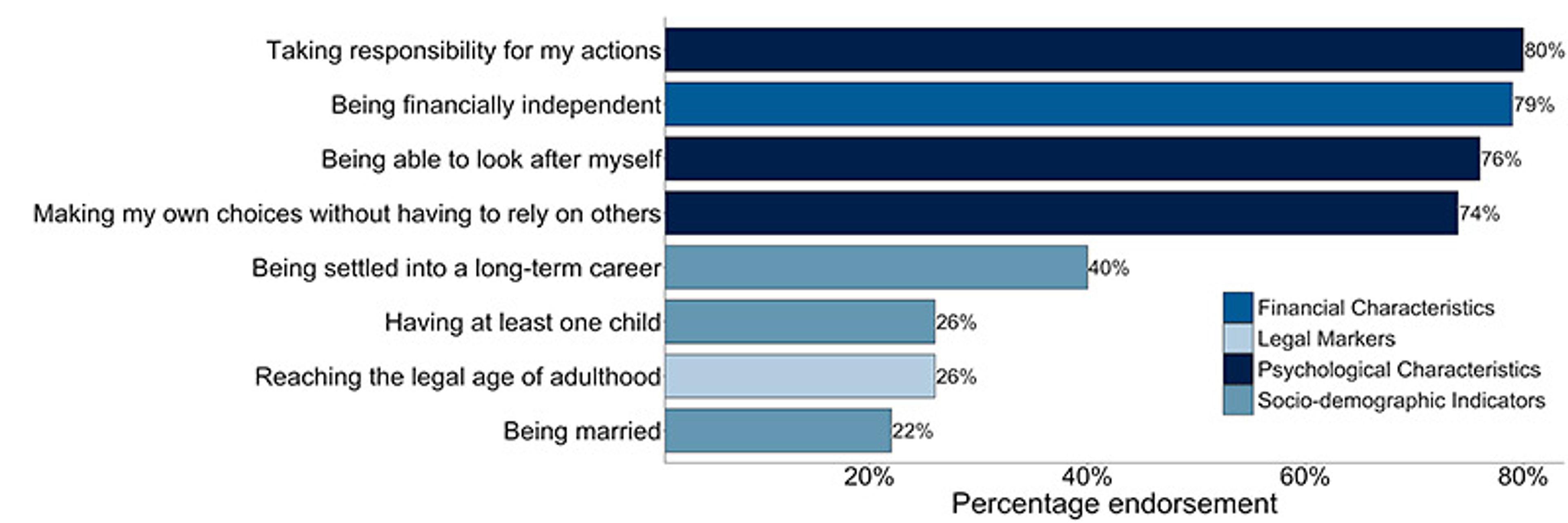

Importantly, we also asked participants which of various characteristics they endorsed as being important for attaining adult status. These characteristics included a list of ‘markers of adulthood’ that researchers have compiled previously, such as being married, being a parent, and reaching the legal age, as well as more psychological ones such as ‘accepting responsibility for the consequences of my actions’ and ‘deciding on my beliefs and values independently’. Similarly, we asked each person whether a number of other psychological qualities defined adulthood for them, using a taxonomy we made that reflects development in areas such as self-reliance, confidence in one’s own knowledge, and social interconnectedness.

Our analysis revealed three key findings. First, the degree to which a person felt like an adult was associated with age, parental status, marital status and attitudes towards adulthood. Participants who were older, had children, were married or had a positive attitude towards adulthood tended to give responses suggesting that they felt more grown up compared with younger participants, those who were childfree or unmarried, and those with a more negative attitude towards adulthood.

We also found that, while people had a positive attitude towards adulthood overall, those who were younger than 30 had more negative views of adulthood. People who are currently aged 18 to 29, also known as emerging adults, might tend to feel more negatively about adulthood for various reasons – eg, entering adulthood during difficult economic times and/or during a global pandemic, which have impacted many young people’s ability to achieve independence and ‘get ahead’ in adulthood. That being said, we can’t be sure whether this relatively negative attitude toward adulthood is characteristic of this cohort specifically or is typical of younger adults of any generation. (It’s possible that, as they age, these emerging adults’ attitudes toward adulthood will grow more positive.)

Setting aside their feelings about being an adult, what did people say defined adulthood for them? They in fact tended to place little emphasis on the traditional milestones of marriage and parenthood: these were endorsed as defining adulthood by only 22 per cent and 26 per cent of our sample, respectively. Reaching the legal age of adulthood, which is 18 in England and Wales, was also endorsed by only about a quarter of participants as defining adulthood – suggesting that, in many people’s eyes, reaching a legal threshold is not enough to make someone truly adult. Respondents in our study were more likely to say they defined adult status based on psychological characteristics such as ‘taking responsibility for my actions’, which was endorsed by 80 per cent of participants, as well as financial markers such as ‘being financially independent from my parents’ and ‘paying for my own living expenses’, which were both endorsed by 79 per cent of participants.

Some of the items that were most and least endorsed as defining adulthood

Among the developmental factors that we asked participants about, aspects related to self-reliance were the most widely endorsed as defining adulthood; ‘being able to look after myself’ was endorsed by 76 per cent of participants. The factor related to social interconnectedness was the least frequently agreed on as a marker of adulthood; for example, ‘having true connections with others’ was endorsed by 37 per cent of participants. These results suggest that the more internal and cognitive aspects of psychological development may be perceived as more important for adult status than external and social aspects of development, at least in some societies.

Defining adulthood largely based on psychological characteristics, as our study participants did, indicates that many people take a fairly subjective view of adulthood – that whether someone is a grown-up is open to interpretation. For many, it seems, the perception that they or someone else is an adult is based less on an external label or specific, well-defined event and more on an assessment of individual development.

It’s worth noting that a number of the characteristics people said define adulthood could be seen as varying across different contexts, even for the same individual. For instance, I might take more responsibility for my actions or make my own choices to a greater extent when I’m at work than when I am staying at my parents’ home. These are also characteristics that can change incrementally, rather than signifiers that are present or not present – eg, I might take more responsibility for my actions now than I did a couple of years ago. Thinking through these possibilities suggests that adulthood is, for many people, not seen simply as a fixed social status, but as a process of becoming that happens gradually over time, and that there can be considerable individual variation in how people perceive their own adult status at any given point.

Only around 28 per cent of people aged 18 to 29 in the US felt they had reached adulthood

It is critical to remember that our research focused on people in a particular society, and that definitions of adulthood will differ based on upbringing, beliefs and cultural background. Cross-cultural research indicates that people living in so-called WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic) countries, which includes the UK, may be less likely to endorse traditional markers of adulthood such as career, marriage and parenthood than people from non-WEIRD countries. Studies have found that participants from China and India place greater emphasis on family obligations compared with US samples, suggesting that traditional sociodemographic milestones may be considered more important for adult status there compared with in more individualistic Western cultures.

Country of origin appears to be relevant to subjective adult status too: in one study, only around 28 per cent of people aged 18 to 29 in the US felt they had reached adulthood, as compared with a majority of people who were around the same age in groups from Ghana, India and China. Future research should include measures such as the ones we used in our recent study to further elucidate cross-cultural differences in the ways people define and perceive adulthood.

However, our work shows that, even within a single society, there are plenty of ways to define being an adult. The research suggests that many people define adulthood more by psychological markers than by social milestones – in other words, adulthood is often seen as being about more than donning the identities of ‘worker’, ‘spouse’ or ‘parent’. Instead, their views reflect that adulthood is a rich and dynamic period of psychological development, one in which individuals tend to become more self-reliant, responsible and self-confident, regardless of when – or if – they reach those traditional milestones.