Humans often appear to react irrationally in the face of disease, as the COVID-19 pandemic has shown. Many cling to religion or become superstitious. Others become fatalistic. In times of plague and trauma, we moderns seek to protect ourselves with prayers, charms, sigils and spells as much as any medieval peasant. That a surgical mask is hygienic doesn’t make it any less of a magical symbol.

But perhaps magic – particularly plague magic – isn’t so irrational. Have humans always pursued the occult arts because they actually work, at least sometimes?

Despite the often blood-soaked history of the use of the term ‘magic’, we must remember that Western history is filled with thinkers who have defended its honour as good natural science – a tried-and-true technology for harnessing interactions between minds and bodies, human and otherwise. And their empirical claims were never tested more than during the centuries of plague.

During the previous millennium, the biggest boom in the practice of magic coincided with the Black Death in the mid-14th century. It was the deadliest pandemic in human history, killing as much as half the population of Asia, Africa and Europe – around 200 million souls. It caused major social and political transformations in the process: slaves, raiders and mystics became kings, and new empires were founded on predictions of the end of time. Plague isn’t merely a medieval curse, either; the bacterium responsible, Yersinia pestis, is very much still with us, genetically unchanged.

The Islamic world, my own area of focus as a historian of science and empire, was hit particularly hard by the plague – termed ta‘un in Arabic, meaning ‘smiter’. There, it helped give rise to what I call the ‘occult-scientific revolution’, where various occult sciences – astrology, alchemy, kabbalah, geomancy, dream interpretation – became an important basis for empire more than ever before. The ability to predict the future with divination, then change it with magic, was of obvious political, military and economic interest, and associated with Alexander the Great in particular. Western Europe saw a parallel upsurge of occultism – much of it from Arabic sources – which we now call the Renaissance. The scientific revolution that followed continued the same trend: historians now admit that saints of science such as Johannes Kepler, Francis Bacon, Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton were likewise raving occultists.

Medicine, too, was often classified and practised as an occult science among premodern Muslim, Jewish and Christian physicians. Many considered it alchemy’s sister, both sciences being predicated on the harnessing of cosmic correspondences and natural sympathies to restore elemental equilibrium in the human body – the definition of health. Techniques for life-extension were also central to the alchemical quest. The sweeping physical and sociopolitical imbalances wrought by plague were accordingly answered by an upsurge in medicine, occult and otherwise.

The Ottoman empire is a prime example of just such a sociobiological transformation. It controlled increasingly large areas of Asia, Europe and North Africa between the 14th and 20th centuries, and plague persisted there for its entire duration. In the name of public health, the Ottoman state sought to purge cities of both physical and moral contaminants, including prostitutes, beggars, illegal immigrants, criminals, bachelors and bachelorettes. While we haven’t gone so far as to outlaw bachelorhood, the effect of our own pandemic is comparable: 2020 and 2021 saw a ramping up of state control, too. Not unlike their modern counterparts in epidemiology and public health, the authors of the most important Ottoman plague treatises were leading scholars striving to combat this existential threat to state and society. They presented plague as a social problem, a disease of the body politic, just as much as an environmental problem. Unlike those of today’s experts, however, their manuals were often emphatically magical.

The most sophisticated and extensive of these manuals was the Treatise on Healing Epidemic Diseases by Taşköprizade Ahmed (1495-1561). As an imperial judge in Bursa and then Istanbul, as well as a famed encyclopaedist, historian and astronomer, Taşköprizade’s approach to this topic was very much cutting edge. His Arabic masterwork deals with the full range of legal, ethical, religious and especially medical responses to plague current by the 16th century, with an emphasis on experimentally proven methods.

Taşköprizade first offers a strong argument in favour of rational responses to plague: obviously, one should avoid or flee plague-stricken areas if possible. Here, he counters earlier Arabic plague treatises that denied the contagiousness of the disease and contested the legal permissibility of fleeing it. He also condemns the fatalistic attitude of some of his contemporaries, singling out mystics for derision. The correct procedure is to have faith in God – then protect yourself and others, preferably medically. Taşköprizade then categorises plague medicine as being either physical or spiritual. The first type includes standard pharmaceuticals derived from plants, animals or minerals; the second includes Quranic prayers and invocations of divine names, planets, angels or jinn by means of mathematical talismans.

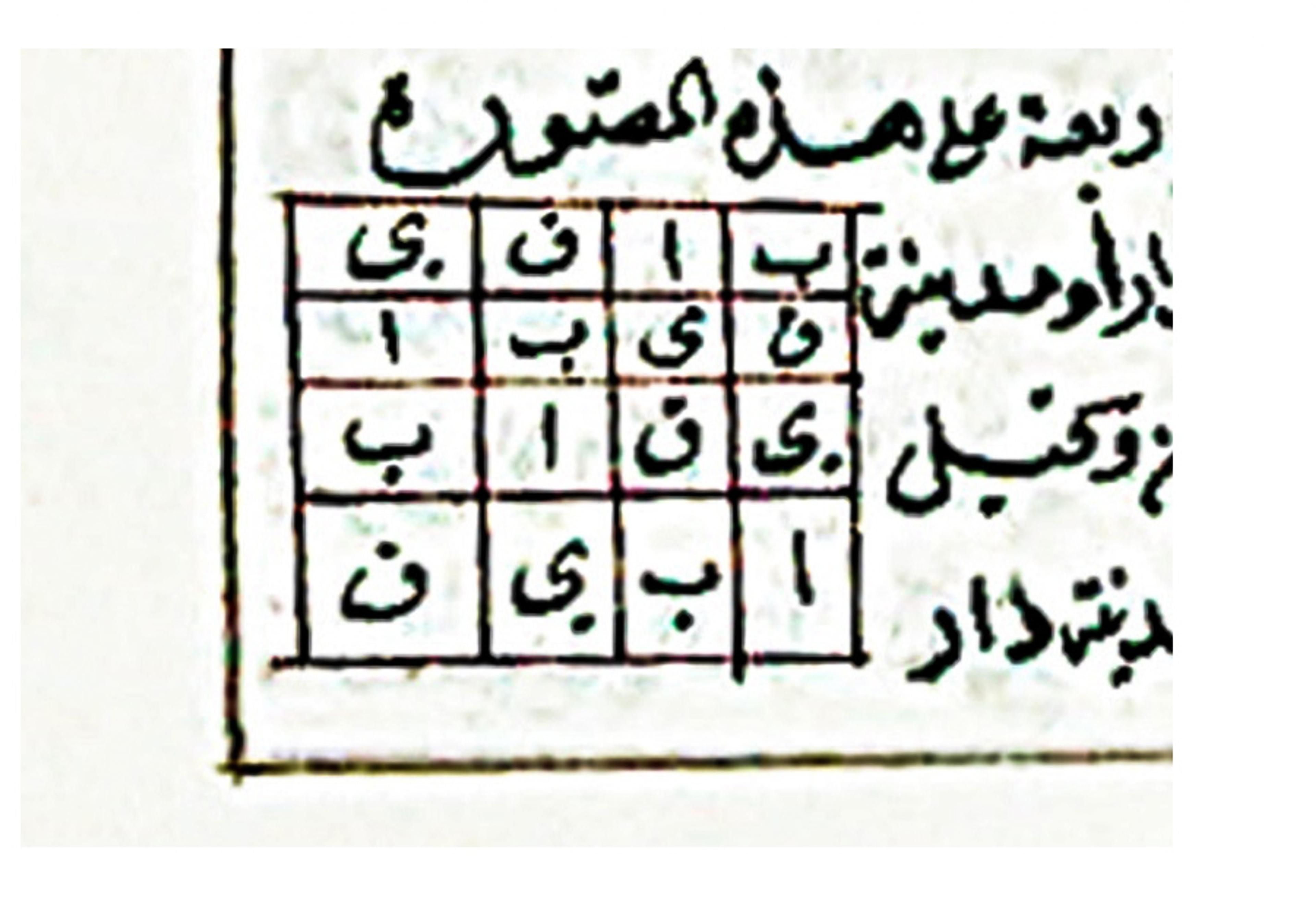

Taşköprizade’s anti-plague talisman featuring a magic square based on the divine name ‘The Perduring’ (al-Baqi), Istanbul, Süleymaniye Library, MS Aşir Efendi 275/1, f 53a. Supplied by the author

As Taşköprizade asserts, however, spiritual medicine is more potent than physical medicine, though the two should always be combined to ensure the best health outcome. Likewise, to him, mental hygiene is at least as important as bodily hygiene for surviving a pandemic. He devotes a full third of this work to detailing a range of occult technologies as the most rigorously empirical means by which one can defend against or cure plague, giving many historical and contemporary examples of their success, some of which he witnessed himself. He ends by citing Plato and the Delian problem – which involves the creation of a cube double the volume of the first – as ultimate proof of the effectiveness of Pythagorean mathematical magic in averting the disease.

Taşköprizade is not unusual in the Western medical tradition in his emphasis on magic as simply good science. Contemporary Latin Christian authors of plague treatises did the same, though they focused more on alchemy than talismanry. But regardless of religious affiliation, wherever the pandemic hit hardest and longest, the occult arts boomed – as a rational, scientific response.

A similar sociobiological transformation took place in the 19th century, when two new pandemics joined plague to ravage much of the Islamic world: cholera and colonialism. The scholarly response was much the same: potions and prayer must be combined to combat them both. Some scholars went further, and declared European invasion to be cholera’s cause and twin, and likewise best resisted by magic.

Under the Qajar dynasty, which ruled Iran from 1785 to 1925, most cities boasted gold anti-plague talismans that were buried at the city limits. The manufacture of such devices was an important service rendered to the state by many early modern philosophers. However, conniving princes reportedly sold some of these devices to English diplomats, after which cholera struck those cities. And both Iranian and Afghan rulers recruited astrologers and talismanists to help drive out Russian invaders. In Morocco to the far west, Mawlay al-Hasan I (who reigned 1873-94) took up the study of alchemy himself in a bid to transform the French into fish and cast them out to sea.

As these examples suggest, it’s normal for humans to turn to magic in times of trauma. So war, like plague, is also good for the occult business. Embattled Muslim philosophers sometimes acted as assassins-at-a-distance as part of their standard imperial repertoire. Similarly, the English occultist Dion Fortune led a Magical Battle of Britain against Nazi German invasion during the Second World War. And during the Cold War, both the Soviet and US militaries invested in psychical research and ufology. Reports of paranormal battlefield experiences are common, too.

Why did, and do, most practitioners of spiritual medicine see it as a perfectly rational response? Why do premodern physicians often report its experimental success? Leaving aside the possible agency of spirits and other nonhuman entities, one factor is certain: the placebo effect. The term acquired its current English meaning in the 18th century thanks to Benjamin Franklin, who took part in a Parisian experiment designed to disprove mesmerism (the therapeutic magnetisation of water and metal). It refers to the clinical effectiveness of inert substitutes in healing disease, as long as the patient believes them to be a real drug. Animals and even plants respond similarly in laboratory experiments.

Despite the often dismissive use of the term, the placebo effect remains one of the most powerful effects in modern medicine. Its twin, the nocebo effect, can be equally powerful: if a patient has been advised to expect a negative side-effect, she could well go on to experience it. As for overall outcomes, even some of the most potent drugs have at most a 60 per cent efficacy, while placebos sit at 35-40 per cent. It’s also not clear to what extent the greater effectiveness of certain modern drugs is due to their marketing.

Under conditions of mass trauma, combined with sincere belief and mental focus, the effectiveness of the placebo often goes up sharply. Individual focus can be equally potent: research has shown that patients under hypnosis can endure surgery without anaesthesia and perform other physiological feats, such as stopping blood loss. Those suffering from dissociative identity disorder – likely a form of self-hypnosis in response to childhood trauma – are likewise able to change their physiology at will, whereby allergic reactions, musculature, body shape, handedness and vision often differ between personalities.

As it happens, creating extreme psychophysical conditions is also a prerequisite to the practice of many occult arts: fasting, prayer, isolation, a vegetarian diet, ritual cleanliness and constant vigil, for weeks, months or even years on end. Psychedelics might also be involved, which similarly produce an altered, hypnotic state of consciousness. The intense mental and physical engagement required by magical ritual can be thought of as artificial trauma: sensory deprivations create medicines that often work. On the other hand, failure to believe or to perform a ritual with technical precision normally results in the failure of the operation.

By any premodern definition, then, the placebo effect is simply a form of magic. Which term we use is unimportant for practical purposes: either way, the fact is that mind can affect matter under the right circumstances. The point is to harness these mind-matter interactions to achieve positive health outcomes.

This powerful, magical effect was recognised and routinely utilised – on the authority of Plato himself – by premodern Muslim, Jewish and Christian physicians. Our triumphalist narrative of scientific progress notwithstanding, and the antibiotic revolution aside, in many cases premodern treatments worked roughly as well as modern medicine. Whether you believe in the authority of celestial spirits or of doctors in white lab coats, the effect is similar: astonishing reversals (or inducements) of disease can sometimes be achieved through the power of belief alone – especially when ritually, traumatically harnessed.

The witch doctor and the medical doctor have more in common than they might suppose. As such, perhaps we should take a page from our premodern predecessors and recognise that physical and mental hygiene are two sides of the same sociobiological coin. Pandemic diseases, once established in local biomes, can almost never be eradicated, only controlled and lived with, as human societies have done for millennia. But fear and paranoia are equally contagious, and can become pandemics in their own right. In a time of global traumas, it seems only rational to use the power of belief as part of our basic hygiene, too.