Many of us have been told at some point in our lives to stand or sit up straight – and usually, with a sense of guilt or embarrassment, we unthinkingly comply. That erect posture is good for you is a truism that we rarely examine or question.

Claims about the benefits of uprightness abound in popular media. ‘Poor posture can make you look older and fatter than you are,’ the New York Times health columnist Jane Brody opined in 1993. An article in Psychology Today in 2024 tells us that ‘good posture activates your assertiveness’ by reducing stress and increasing positive mood and self-esteem. And then there is the assumed value of upright posture to physical health, especially back-pain prevention. In an article from 2023, the website of the AARP (formerly the American Association of Retired Persons) advised readers to stand up straight in order to ‘avoid nagging pain’. The magazine Today’s Parent in 2021 directed caregivers to teach ‘spinal hygiene’ to young children: ‘Their backs will thank you later.’ Even the US National Institutes of Health promotes a similar message: ‘years of slouching wears away at your spine to make it more fragile and prone to injury,’ the agency informs us.

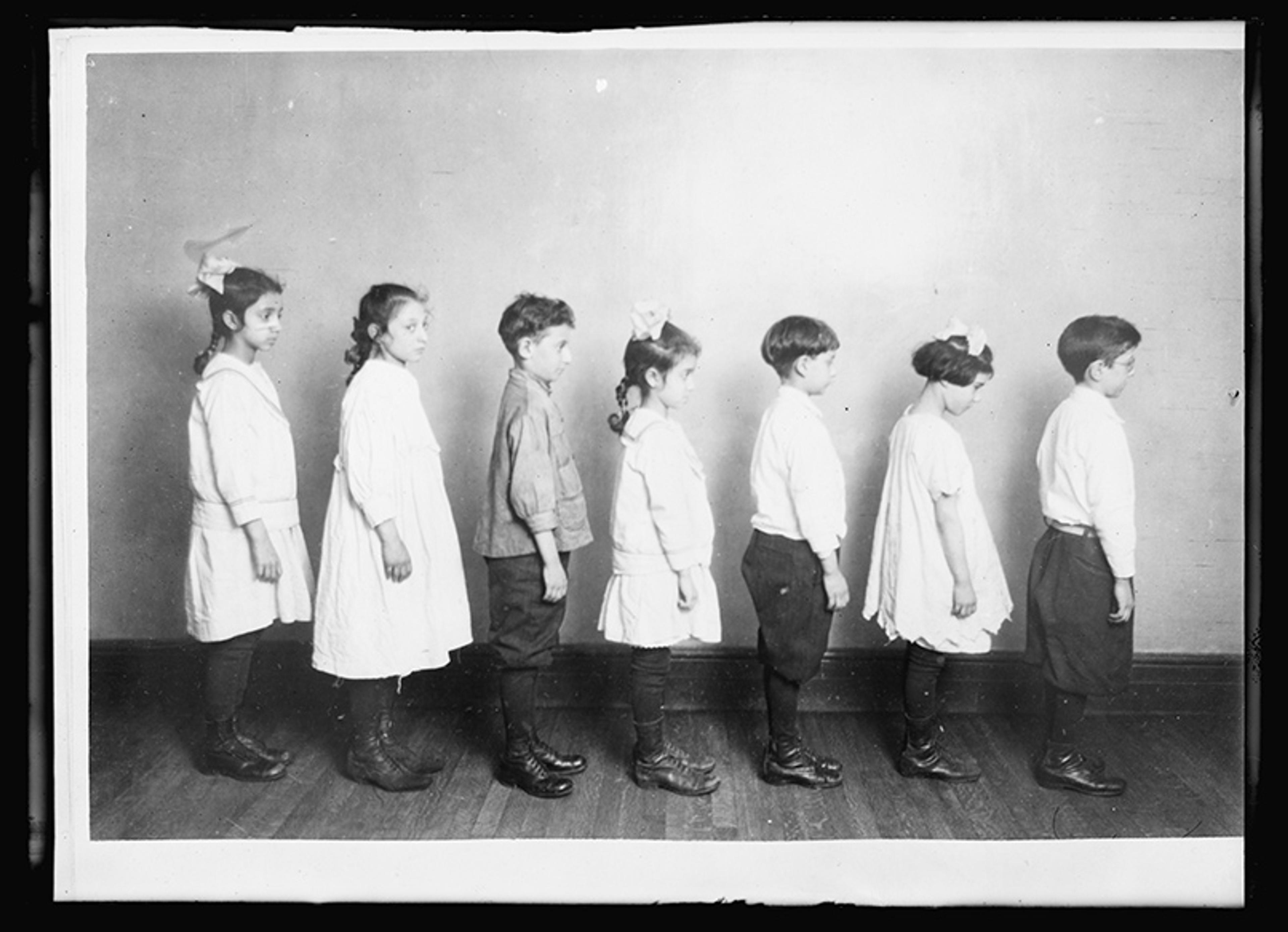

Children at a Red Cross posture class at Barrow Street, New York County Chapter, standing with incorrect posture before instruction, 1922. Courtesy the Library of Congress

Having spent more than a decade studying the posture sciences of the past and present, I am still stunned at how often these fear-mongering articles appear, especially since there is negligible evidence to support a causal link between slouching and back pain in an otherwise healthy person. Studies show that, for back-pain sufferers, individually tailored posture work with a physical therapist can help, and good form can help prevent injury in certain sports such as weightlifting. But using posture training as a preventive measure for back pain – especially the crude mandate of ‘stand/sit up straight’ – seems to have little effect. Indeed, a recent Australian study found that, for young women, a slight slump in the upper back may actually be ‘protective of neck pain compared with upright posture’.

Why, when many health experts and journalists know that the aetiology of back pain is notoriously complex and opaque, do they revert to simplistic, reductionistic claims warning against the bad effects of slouching? One way to understand the staying power of this misleading health message is to look into its historical origins.

The dedicated scientific study of human posture emerged in the wake of Charles Darwin’s books On the Origin of Species (1859) and The Descent of Man (1871). In these works, Darwin argued that the first and most crucial step of human evolution was upright standing, with bipedalism preceding brain development and language acquisition. Darwin’s prioritisation of uprightness and of the human spine upended centuries of work conducted by natural philosophers and anatomists who understood intellect (often measured by brain or cranial size) to be the defining feature of humankind. The posture-first process of evolution is still widely accepted among most practising scientists today.

Many of the first devotees of Darwin’s posture-first theory were physician-anthropologists, such as Sir Arthur Keith, who lectured the Royal College of Surgeons on ‘Man’s Posture: Its Evolution and Disorders’ in 1923, and the physician Eliza Mosher who, together with the physical educator Jesse Bancroft and others, founded the American Posture League (APL) in New York in 1914. These early posture scientists took Darwin’s evolutionary ideas about posture and applied them to present-day settings and people.

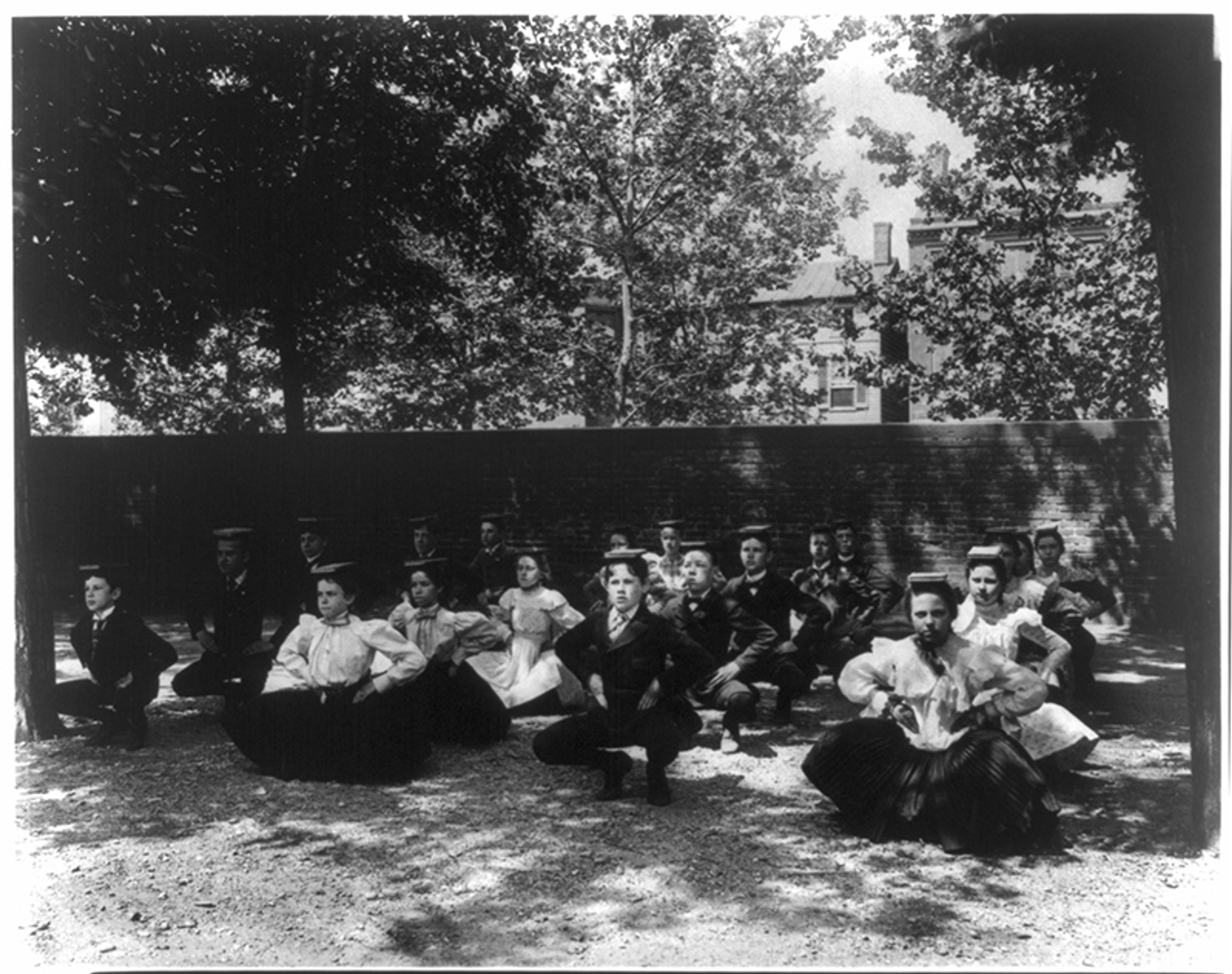

Posture exercises, c1899. Courtesy the Library of Congress

For instance, when Mosher and Bancroft travelled the streets of New York, they claimed to see three types of slouchers: (1) upper-class types who modelled themselves on the popular Parisian ‘debutante slouch’ fashions; (2) middle-class professionals who increasingly adopted a sedentary lifestyle brought about by mechanised travel and new forms of desk-work; and (3) tenement immigrants – the ‘huddled masses’ in the words of the poet Emma Lazarus – who, given their subpar dwellings and backbreaking working conditions, lived with a near-constant threat of disease and chronic pain.

Influenced by warnings from popular eugenicists of the time that the country’s population was at risk of intellectual and physical degeneration, Mosher and Bancroft portrayed the APL as a national strengthening project, bringing about health, discipline and a universal standard of good posture that could and should be adopted, no matter what race, sex, class or creed. They argued that as many as 80 per cent of US citizens had lost their ‘naturally evolved’ and healthful postures due to frivolity and leisure – a problem seen among the upper and middle-classes – and to unhealthful industrialised work sites, which affected the working poor and marginalised others.

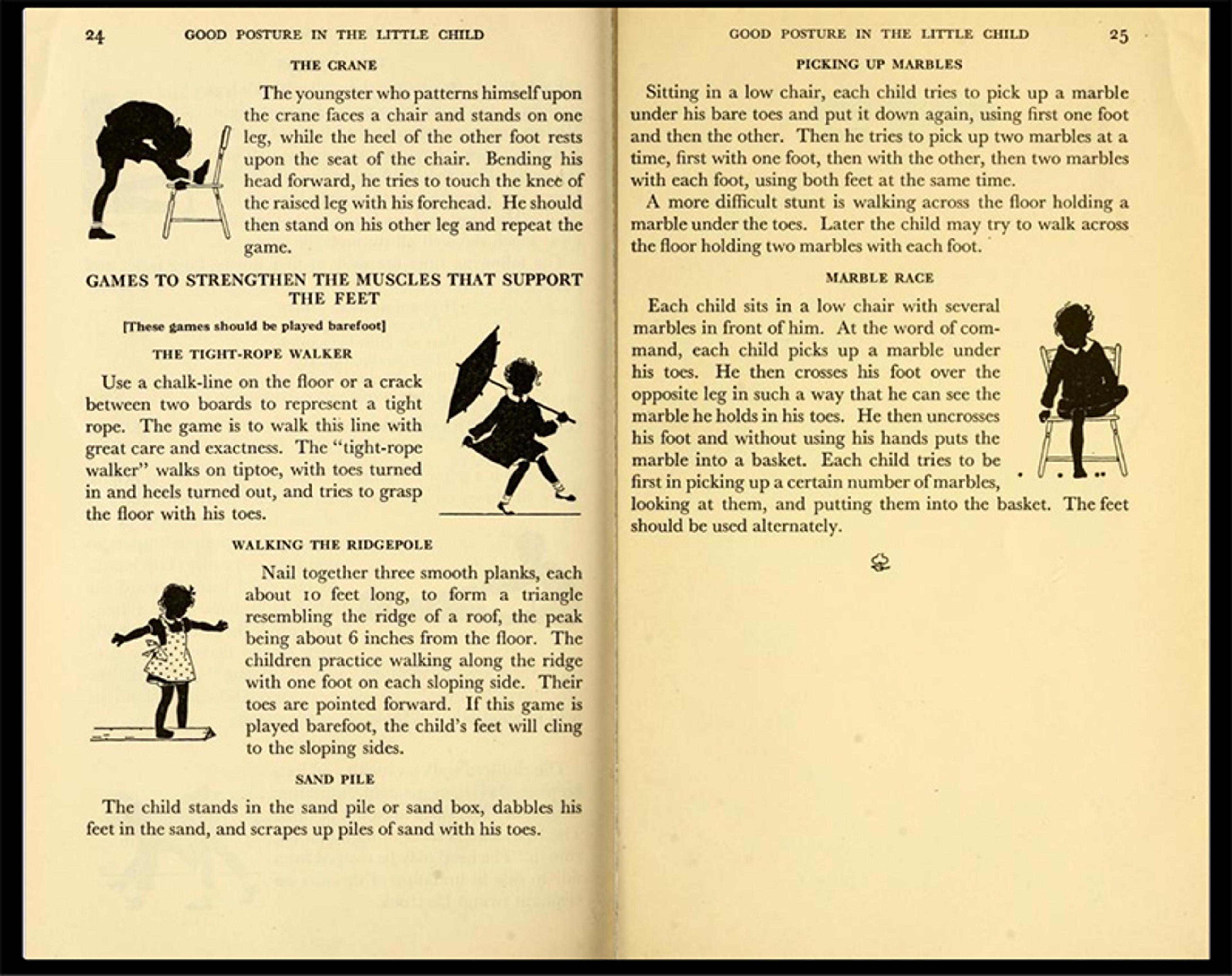

From Good Posture in the Little Child (1933). Courtesy Internet Archive

Together with 70 of their professional peers who constituted the APL, Mosher and Bancroft created standardised posture exams, posture-enhancing technologies (mainly chairs, clothing and shoes), and illustrated educational pamphlets and posters depicting ‘plumbline posture’ – human figures in silhouette, with head, shoulders, chest, hips, knees and toes all neatly stacked on top of each other, forming a straight line from top to bottom. Maintaining this line, the APL argued, could ward off disease, such as tuberculosis, and prevent a future of disabling pain.

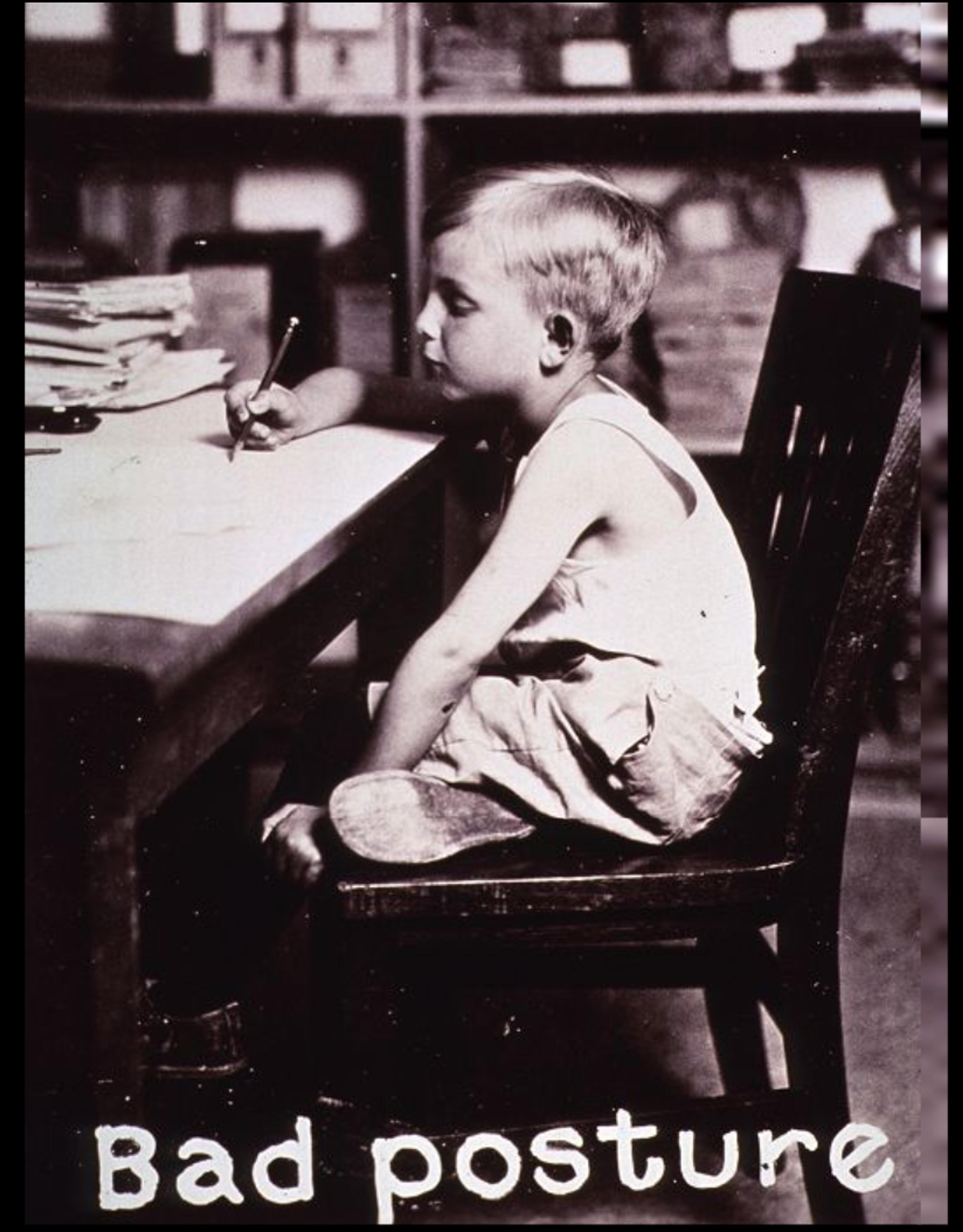

Courtesy the National Library of Medicine

This was an era when preventive medicine was becoming a dominant force in US healthcare. Preventive health fit with free-market ideologies and a fiscally conservative US government that time and again refused to adopt a system of universal healthcare and treatment for its citizens. As such, the tests and educational materials that the APL offered were eagerly adopted by the US public health service and distributed to publicly run schools, the US military, colleges and industry.

In all of these settings, officials introduced mandatory posture exams, which became a rudimentary surveillance technique for sorting the healthy from the unhealthy, fit from unfit, nondisabled from disabled. A person with the slightest slump could easily be placed in the unhealthy group, with negative consequences for their future. The historical record offers numerous examples of immigrants with spinal deviations being refused entry to the country, of job applicants with scoliosis who failed to gain employment, of children with detectable curvatures not permitted to undertake a formal education. Posture surveillance became part and parcel of the long history of disability discrimination in the 20th century, a legally accepted practice until the passage of Section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act, which prohibits disability-based discrimination by federally funded programmes and activities.

One can understand, then, why the market for posture correction bloomed in the first two-thirds of the 20th century. If you wished to pass as nondisabled and gain entry to schools, universities and the workplace, you needed to keep your posture in check. Those who missed out on the gospel of good posture or could not afford to spend the time or money on such improvement measures were further marginalised. At the same time, the rising rates of back and neck pain through the 20th century were blamed on individuals not doing enough to prevent these issues. Although the APL disbanded in 1944, the belief that back pain was preventable through posture maintenance was adopted as an obvious truth that lingers to this day. Accordingly, to control back pain, public health officials and clinicians focused on wellness programmes and individual lifestyle choices, rather than looking to address more complex structural causes, such as unhealthy working conditions and social inequality.

This history is not unique to the US. By the early 20th century, the posture sciences had been taken up globally, often used as a tool for nation-building, militarism and cultivating strict definitions of citizenship along racist and ableist lines. In his autobiography Born a Crime (2016) about growing up in South Africa, the comedian and political commentator Trevor Noah succinctly addresses the extra vigilance required of Black men and their posture in a white supremacist society. ‘For centuries,’ he writes, ‘coloured people were told: Blacks are monkeys. Don’t swing from the trees like them. Learn to walk upright like the white man.’ In Nazi Germany, the police used posture tests to determine criminality, based on the racist claims of scientists, such as the anthropologist Hans F K Günther who believed that ‘the virtues of the Nordic were expressed in its male body type, with its straight posture, pronounced chest, and small abdomen.’ Erect posture, he argued, was alien to Jews and ‘to the Eastern man, whose appearance was the negation of the beauty ideal of the Occident.’ Meanwhile, the Chinese republic’s Department of Health published brochures very similar to the APL’s, advising ‘a good child must have good posture’.

Likewise, fitness systems emphasising the development and maintenance of upright posture originated and travelled across the globe. Take, for example, the German-born Joseph Pilates, who perfected and popularised his system in the US. Or the Ukrainian-born Moshé Feldenkrais, who developed a posture-centred exercise programme that was taken up by Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion. And there is the unique style of yoga created in the mid-20th century by India’s B K S Iyengar who insisted on posture precision in all of his sequences.

There is an urgent need to dispel the medicalised myth that poor posture leads to bad health

While we no longer live in a world of mandatory posture screenings – save for the few countries that still conduct scoliosis exams, such as the US, Japan and parts of China – both the posture-correction market and the misguided belief in the preventive powers of such technologies remain. Today, corporate heads of Google, Facebook and other prominent online organisations have embraced the message, and posture-enhancing devices – from biometric posture ‘trainers’ that connect to your smart phone, to chairs and even bras – account for approximately $1.25 billion spent annually worldwide. This market – aided and abetted by gullible media reports – still largely relies on the simplified plumbline standard of good posture first espoused by the APL more than a century ago, taking it as a sign of ideal human form and of healthful living that will prevent future pain.

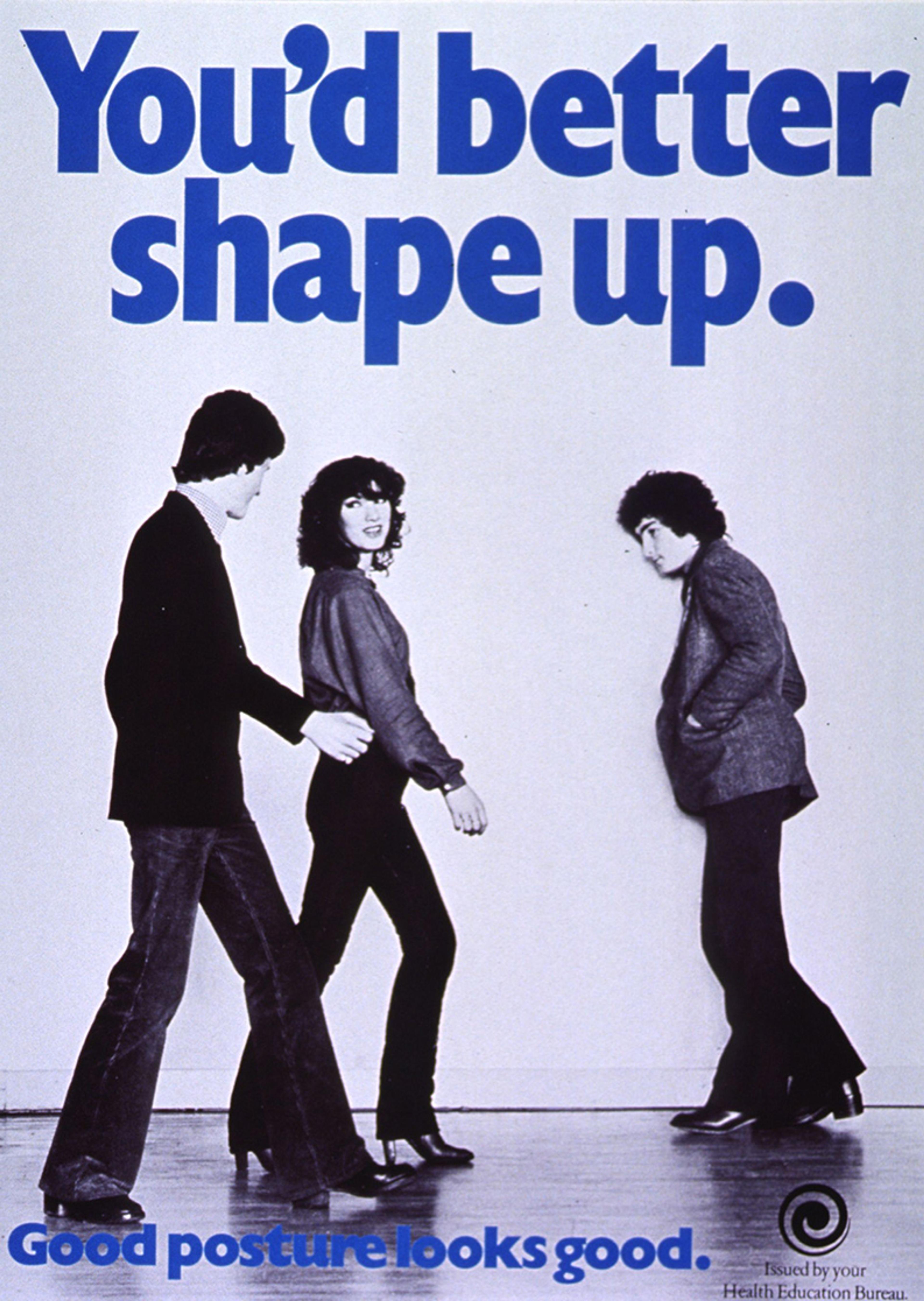

Irish government campaign, 1970s. Courtesy the NLM

And yet, scientific evidence suggests that there is a significant amount of variation in spines across the human population and that the human spine is incredibly dynamic and resilient, all of which brings the idea of a universal plumbline standard of human posture into question. What’s more, there is little evidence to suggest that human posture serves as a meaningful health indicator. In an academic paper published in 2019, physical therapists working in Qatar, Australia, Ireland and the UK argued there is an urgent need to dispel the medicalised myth that poor posture leads to bad health. The authors insisted that the mandate to stand up straight is scientifically dubious, ‘reinforced by long-standing stereotypes’ and ‘fear-inducing messages in the mainstream media’. They continued, ‘people come in different shapes and sizes, with natural variation in spinal curvatures.’

On the face of it, posture-improvement campaigns – whether for workplace success or physical and mental health – may seem rather innocuous. What is the harm, after all, of engaging in posture exercise programmes? Of buying chairs, shoes and devices that help you stand straight?

On an individual level, it is entirely possible that taking up yoga or purchasing an ergonomic chair will bring you an enhanced sense of wellness. But when looking at the long history of posture-improvement campaigns, it’s clear they were driven by misguided values and bad science. Instead of bringing about improved health for all, they fuelled discrimination, blame and the growth of a neoliberal approach to health care – a means of preventive medicine that is in reach of only those who can afford it.

We need a more nuanced notion of what good posture is and for whom, not a reductive plumbline that is based on a eugenic ideal. We also need to be mindful of the reality of physical diversity and variation – not everyone who is told to stand up straight can, and thus such a message perpetuates ‘othering’ those who do not comply with assumptions about what constitutes a ‘normal’ human body.