Last year, I was invited to give a talk about Claude Monet’s painting The Water-Lily Pond (1899). Trouble was, I didn’t know much about Monet. I am a philosopher, working primarily on phenomenology, which is, in a nutshell, the study of conscious experience. It is about analysing the structure and dynamics of perception, imagination and emotion as they appear to the experiencing subject. The recurrent motto is: ‘Back to the things themselves.’ So, I found myself getting back to a very particular thing – Monet’s painting of his pond at Giverny.

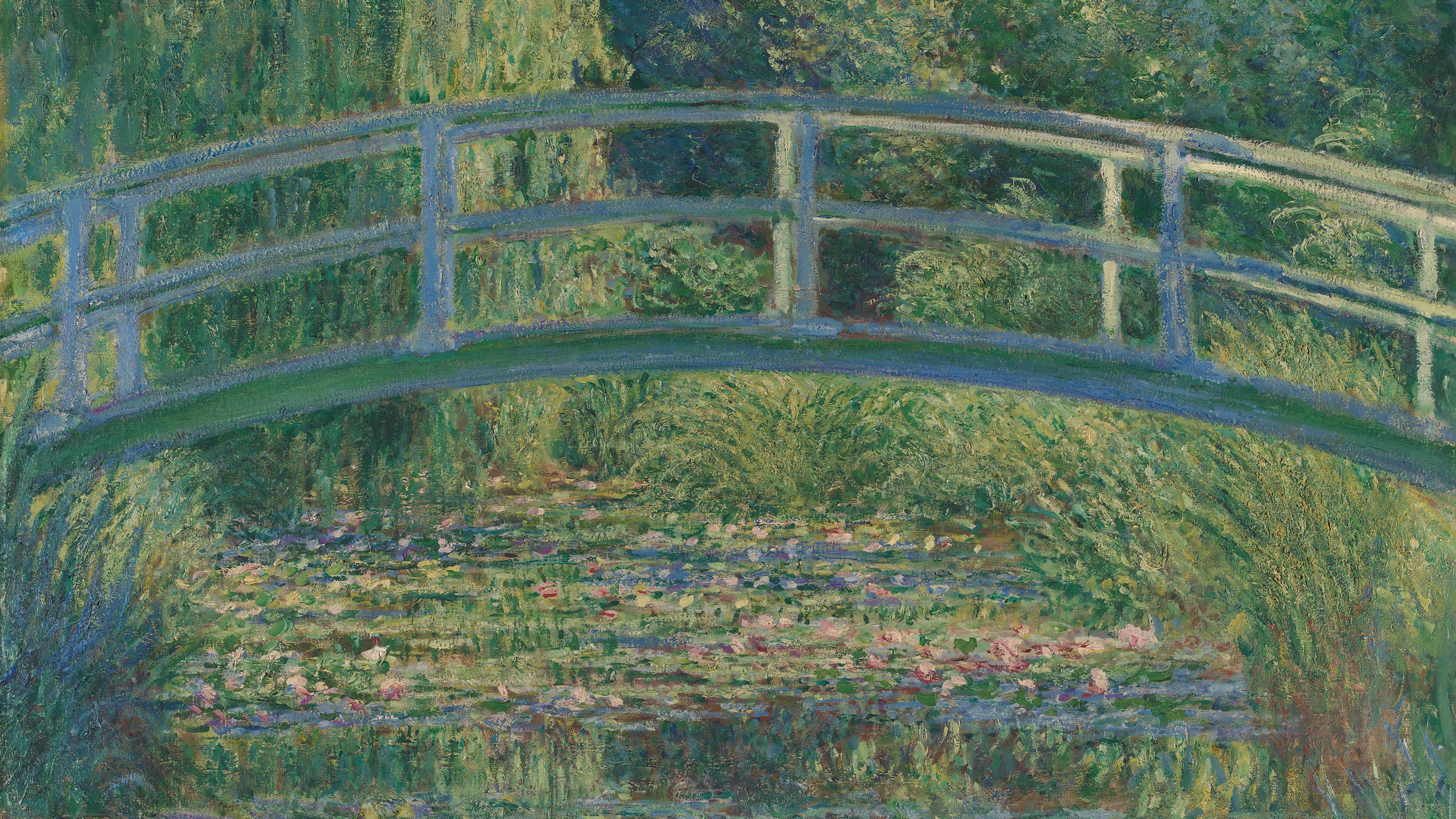

The Water-Lily Pond (1899) by Claude Monet

The painting is still, but not completely: there is some dynamism, some slow play of light and shadow, of forces between the foreground of the water, the background of the trees, and the hanging Japanese bridge. And there is a sense, once you’ve been looking at the painting for a while, of being there. It is very immersive, especially for such a small painting. It’s as if Monet were inviting us into his garden.

This immersiveness does not come from an illusion of being in three dimensions – the opposite, in fact. Monet does a few subtle things that destabilise the elements of the perspective. The bridge looks two-dimensional. The whole painting is framed as if it were cropped (no shore where the viewer is; no banks for the bridge). The horizon is eclipsed by thick foliage, so that we cannot see the focal point. Even from the viewer’s point of view, the origin of the perspective is ambiguous. It is hard to gauge depth. If you look at it for a long time, elements of it seem now closer, now further away.

The art critic Clement Greenberg explained, in his essay ‘The Later Monet’ (1956), that Monet removes elements of three-dimensional form as a way to generate an atmosphere – something elusive that is at the core of both our experience of art and of our experiences in daily life. In this case, the feeling of serenity and the immersion come from Monet’s flattening of the perspective. And creating this atmosphere really seems to have been one of the main obsessions for Monet, who said:

For me, a landscape does not exist in its own right, since its appearance changes at every moment; but the surrounding atmosphere brings it to life – the light and the air which vary continually … For me, it is only the surrounding atmosphere which gives subjects their true value.

Atmosphere exists as a scientific term, denoting the gases enveloping a planet. But it seems that Monet means something different here. There is another sense of atmosphere, the folk sense, which is the pervading mood of a place. A carnival might have a joyous atmosphere, a cathedral a lofty atmosphere, the moors a melancholic atmosphere. There is this sense of the mood of the landscape, which changes with light and air, but which, according to Monet, brings the landscape to life, and reveals the ‘true value’ of the things in that landscape. The idea is that any element in that landscape (the bridge, a lily pad, etc) has the effect on the viewer that it does because of the atmosphere that the artist has managed to create.

What is striking for me is that Monet was foreshadowing advances in philosophy that have only recently made it into mainstream discourse. There has been a renewed focus on atmospheres in phenomenology, and this trend has now permeated into geography, anthropology and architecture. People in each of these fields are trying to understand what atmospheres are exactly, how they affect us, and how they are generated. Something of a common ground is this: atmospheres are phenomena that characterise spaces (real or imaginary) and are grasped prior to any reflection, through our bodies and our feelings.

Atmospheres are ephemeral. And yet, it is a recurring notion that atmospheres are somehow the heart of the place, something that Monet hints at when he says that landscapes come to life only through their atmospheres.

Monet’s approach, I would argue, sheds light on how atmospheres work. Again, he goes as far as saying that the atmosphere gives the elements in the painting their ‘true value’. This is a radical idea. If anything, most people, when thinking about how they experience a scene, would follow an atomist view: there are small elements that join together to make bigger elements, and bigger elements (a table) combine into even bigger ones (a dining room). And then the atmosphere comes last. The atmosphere of The Water-Lily Pond, for example, would be made out of the bridge, the pond, the trees. But Monet says that it’s the other way around: the bridge, the pond and the trees emerge thanks to the atmosphere.

Some phenomenologists have suggested similar ideas. To be in the world is to be oriented affectively towards it. Heidegger developed this idea with the concept of Stimmung (or ‘fundamental mood’), the idea that we are always in some kind of mood or another, and that this transforms how we engage with the world. In the essay ‘Lost in the Supermarket’ (2017), Dylan Trigg takes this idea further and considers how, at a fundamental, pre-reflective, bodily level, we feel the atmosphere of a place, tuning to it so that we are in a certain mood. Even a run-of-the-mill place like a supermarket can, at times, become charged with an anxious quality, for example, and one’s whole experience of the world is then shaped by that sense of anxiety. The atmosphere is primordial, and the elements that we experience in the landscape emerge out of that basic atmosphere.

People can recognise the gist of a scene incredibly quickly, accurately and almost effortlessly

There are some very interesting findings in experimental psychology that point in a similar direction. A common psychology trick is to show subjects an image for a very short time, to see how fast perception can be, as well as which elements of the image are processed at which speed, and at which level of consciousness.

As it turns out, people can recognise the gist of a scene incredibly quickly, accurately and almost effortlessly. You flash the image by, and people can say: ‘Forest!’ ‘Building!’ Or things like: ‘Serene!’ ‘Scary!’ Even when you blur the objects in the scene, the overall gist is extracted.

It seems that extracting the gist of a scene (the Gestalt) is often the priority for the perceptual system. We get the atmosphere; the rest comes later. And if you put objects in incongruent atmospheres (eg, a priest on a football pitch, a footballer in a church), they get processed worse and more slowly. This is actually an everyday affair: you flip through the photos in your phone quickly, and you get a gist of each scene. The primacy of the gist of the scene – its atmosphere – was something that both philosophers and Monet intuited.

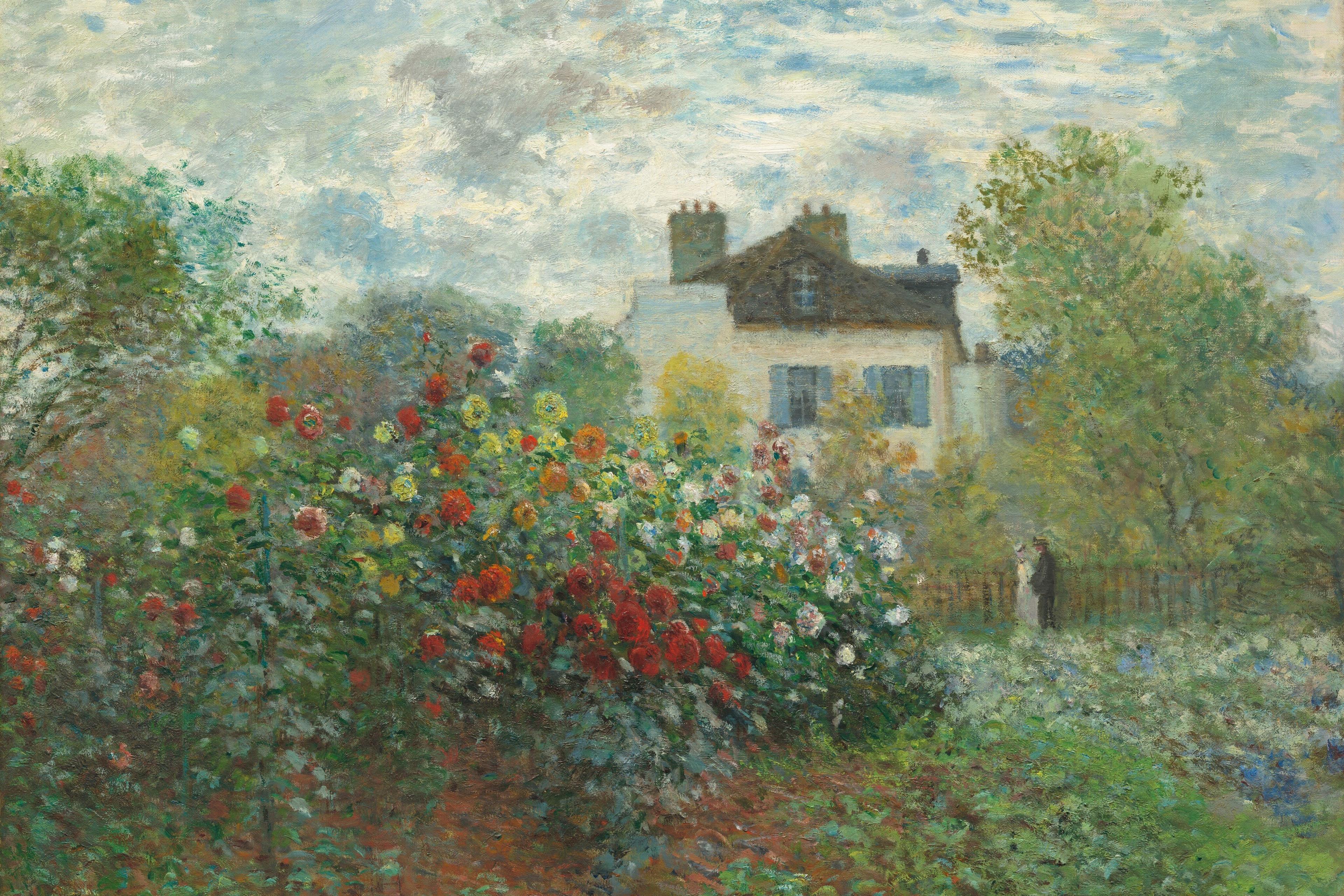

Legend has it that, in 1871, Monet went to Amsterdam to escape the Prussian siege of Paris. He walked into a food shop where they were using Japanese prints as wrapping paper. Awestruck, he bought some right away. This was the beginning of an obsession for Monet, who collected hundreds of these prints.

There are many elements of the Japanese art genre ukiyo-e that you can also see in Monet. Katsushika Hokusai went around Mount Fuji capturing 36 views of it, at different times, in different seasons. Monet painted the changing light on the façade of Rouen Cathedral in more than 30 paintings. He also painted his own garden again and again, until he lost his sight. In The Water-Lily Pond, destroying the linear perspective that is characteristic of Western art seems to facilitate the immersion into the garden and its atmosphere. Stylistically, you get this opening and occluding of views in Hokusai as well. He uses clouds, especially, to do this.

Honganji at Asakusa in Edo (Tōto Asakusa Honganji), c1830-32, from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei) by Katsushika Hokusai. Courtesy the Met Museum, New York

Rouen Cathedral, West Façade, Sunlight (1894) by Claude Monet. Courtesy the NGA Washington

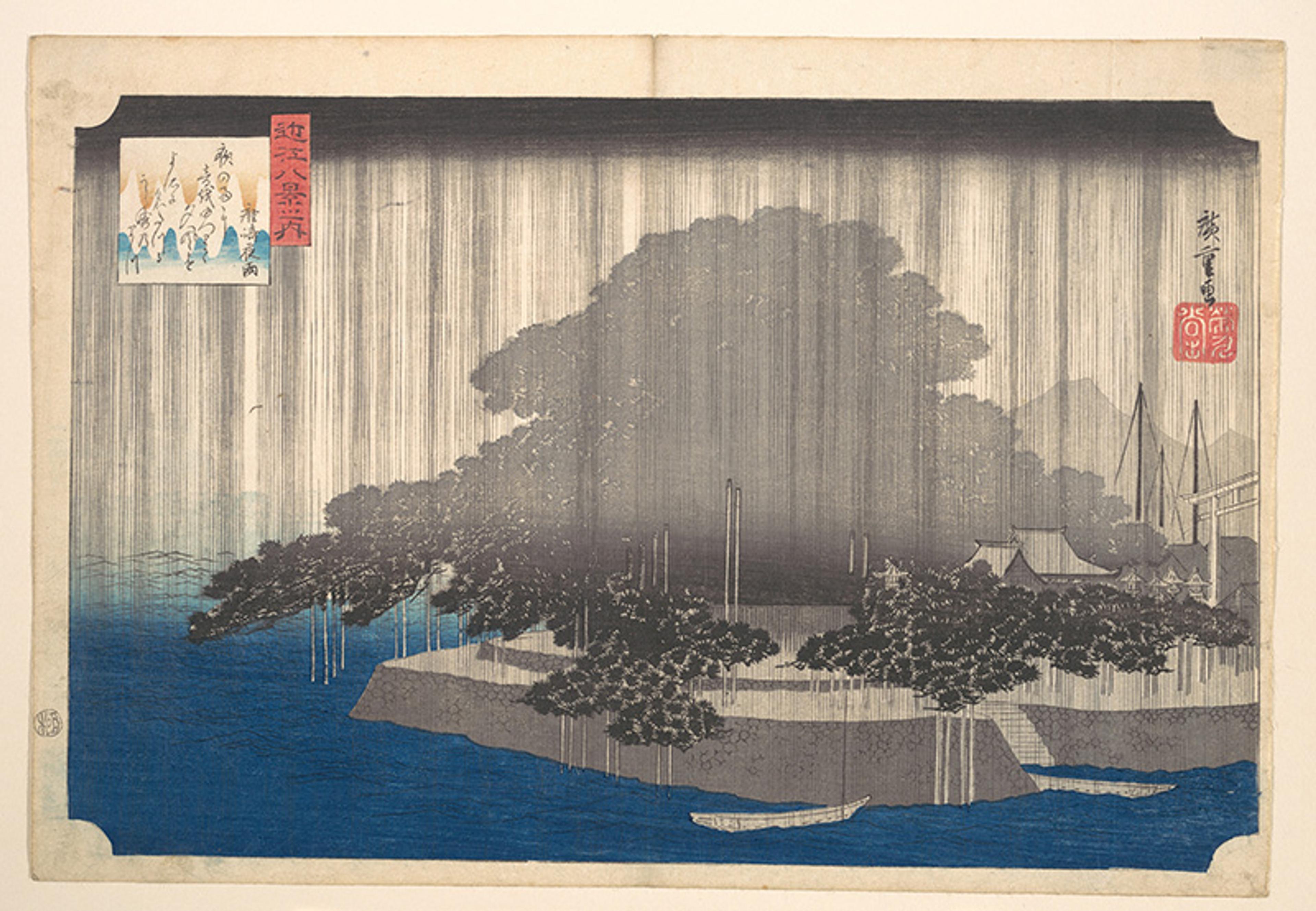

Monet’s ideas about opening and occlusion, about the destabilisation of perspective to create immersion, can be traced back to Japanese woodblock prints. And they are all about atmospheres. This is clear in Hokusai, and it is perhaps even clearer in the work of his fellow artist Utagawa Hiroshige. In one of the first treatises on Hiroshige in the West, Mary Fenollosa called him ‘the artist of mist, snow and rain’. In an essay published in 1901, Fellonosa wrote:

Sometimes a whole picture is of a uniform leaden tone. A sheet of water falls helplessly from the upper to the lower edge. Trees and houses are black, sullen, soaked through and through with rain. You feel instinctively the essence of a rainy day in June. Gloves might mildew if kept in a drawer with this picture.

Evening Rain at Karasaki-Pine Tree (c1832) by Utagawa Hiroshige. Courtesy the Met Museum, New York

Here again, we get a play of light and air to create an atmosphere, which then reveals the true character of the scene (‘the essence of a rainy day in June’). The overall-gist feeling of the depicted scene determines how we experience the elements therein. In this way, Hiroshige, too, vividly demonstrates the primacy of atmospheres.

When any of us enter a building or a landscape, we sense the atmosphere not just by looking, but by moving through it. And the atmosphere, in turn, pulls us in different ways. A cheerful atmosphere pulls us to dance, a lofty one pulls us upwards, an ominous atmosphere makes us shrink.

Many of Monet’s last paintings were destined for the Orangerie Museum in Paris, in rooms that he helped design to host long, horizontal panels. Each room is a kind of oval, with a low ceiling that lets in the light in a subdued way. The murals’ low placement in relation to the visitor’s body, coupled with the fact that they surpass most people in height, maximises the sensation of immersion. And the way the rooms are set invites you to move along the painted ponds. There is a liquidity to the way that one moves through those rooms that very much makes you sink into the otherworldly serenity of the paintings.

Murals from the series Water Lilies by Claude Monet at the Musée de L’Orangerie in Paris, France

Throughout his work, Monet demonstrates the power of atmospheres and how they can be crafted. I think there is a lot to learn from him about how we experience the world, because our lives are a constant journey through ever-changing atmospheres. As you move from one building to another, from a garden to the street, notice how the changes in light, the opening and closing of vistas, affect your mood, subtly altering your very sense of being. They are hard to notice and easy to forget, but much of what you perceive, of what you think, of what appears possible, is determined by atmospheres.

Material for this article was originally presented as a talk at the York Art Gallery during the exhibition National Treasures: Monet in York ‘The Water-Lily Pond’.