To read Nan Shepherd is to feel as if one has been plunged into the rocky crags of the Cairngorm Mountains of Scotland – the landscape she wrote about with such adoration in The Living Mountain (1977). For Shepherd, ‘Each of the senses is a way in to what the mountain has to give.’ Through her poetic imagination and lyric innovation, one arrives at a dissolution of boundaries between body and nature. It makes for a thrilling reading experience. Shepherd offers a keen and precise observation of the mountains coupled with a kind of prismatic perception, which gracefully unfolds to provide an intimate portrait of the ecological terrain she called home.

Shepherd writes about her body’s interaction with the Highland landscape, where ‘Place and a mind may interpenetrate till the nature of both is altered.’ Her engagement with the Cairngorms, ‘the whole plateau burning with a hot violet incandescence’, where one can ‘be so open and yet so secret’, is replete with language suggesting a relational, and feminine, embodiment. As she walks, Shepherd experiences an overwhelming connection with the landscape, and discovers that ‘a mountain has an inside’, an interior, with which, through repeated intimate encounters, she forges an energetic relationship. She is vulnerable in its energy, while each detail of the mountain stands ‘erect in its own validity’. The language is sexual, inherently physical, as Shepherd allows herself a form of climax, whereby ‘Like drink and passion, [a love of the hills] intensifies life to the point of glory.’ Touch, she says, ‘is the most intimate sense of all … [and] the hands have an infinity of pleasure in them.’

In gifting the reader such an intimate encounter with the landscape, Shepherd sets up a kind of complicity, so that, while reading her, one envisions oneself on the mountain with her, in a collaborative surrender to the landscape. As she writes: ‘I had an odd sensation of being actually myself up there … It’s queer and invigorating.’ As is Shepherd’s book.

The Living Mountain chronicles her years of walking the Cairngorms before and during the Second World War. Though she had written three previous books – novels depicting the constraint of women’s lives, published in quick succession between 1928 and 1933 – she left The Living Mountain to sit in a drawer for more than 30 years until it was eventually published in 1977. In her biography Into the Mountain (2017), Charlotte Peacock suggests that Shepherd wavered over publication because of the sensual nature of the book: that she worried it wouldn’t be taken seriously in a male-dominated field of science and literature. As the nature writer Robert Macfarlane noted in The Guardian in 2008: ‘Shepherd was a woman writing out of a Highland Scottish culture in which cherishing of the body was not easily discussed.’ Of course, it is this very quality that makes her extraordinary to read today; the record of her ‘traffic of love’ with the mountain is a testament to her strength as an independent woman writing toward a new paradigm in nature literature. ‘I am a mountain lover because my body is at its best in the rarer air of the heights and communicates its elation to the mind,’ she wrote; and: ‘love pursued with fervour is one of the roads to knowledge.’ Her book, in essence, documents her love affair with a mountain.

Born at the tail end of the 19th century, Shepherd spent most of her life in Cults, a semi-rural suburb on the outer edges of Aberdeen. She was one of the first women to graduate from the University of Aberdeen in 1915. For 40 years, she lectured in English at the city’s College of Education, writing poems, essays and articles for various journals and magazines, and when she wasn’t writing she was hill walking. Former students describe her as having always been far away, somewhere else, which makes sense if she was eternally thinking about returning to her beloved mountain. Friends knew her as an enthusiastic, dedicated teacher, and while she remained unpartnered and solitary for much of her life, some speculate that she kept a lover later in life for whom she wrote several love sonnets in her last book of poetry. The three autobiographical novels she published in the 1920s and ’30s established her as a modernist voice in Scottish literature, even as she is principally remembered today for The Living Mountain.

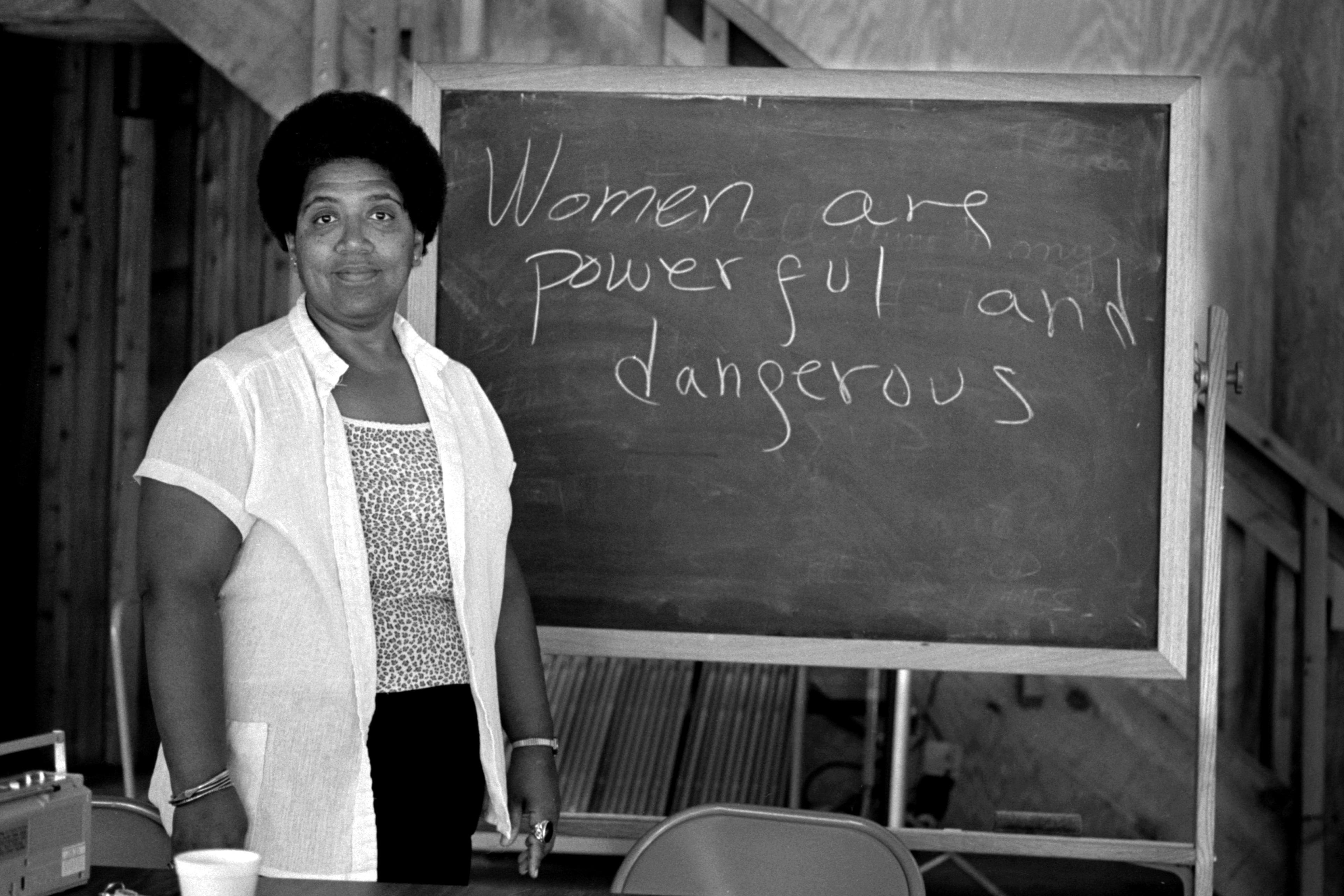

The Scottish writer and critic Alice Tarbuck notes that Shepherd was considered ‘dangerous’ for walking barefoot alone, remaining unmarried, and creating an independent life for herself while challenging masculine norms at a time when this was unheard of, even risky. Yet it is precisely Shepherd’s outsider perspective, her position as ‘other’, that marks The Living Mountain as a core text for queer ecology.

Mainstream traditions within nature writing follow a certain narrative lineage, ripe with hyper-masculine stories sharpened by patriarchal values. The dominant ‘nature’ stories we’ve inherited suggest a separateness between the wild and everything human. Luminaries of this tradition include Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, Edward Abbey, Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson – writers who’ve given us pathways to consider the immensity and profundity of nature from a romanticised standpoint of wonder and self-immersion. And yet there is an omission of gender, of queerness, of the feminine, and of the body, in these writings. Queer ecology disrupts this patriarchal tradition, melding ecofeminism with the underlying tenets of queer theory to offer an alternative pathway for writing nature. As Greta Gaard argues in ‘Toward a Queer Ecofeminism’ (1997), and Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands writes in ‘Unnatural Passions?: Notes Toward a Queer Ecology’ (2005), queer ecology embodies a sense of care; that is, a reciprocity between the human and the wild that is spacious and continuous, transcending imposed binaries such as human/nonhuman or male/female while aspiring to a collective belonging. It’s about range and multiplicity.

Queer ecology asks us to embrace the porous, to eliminate boundaries between self and nature, and to celebrate a diversity within our landscapes that can help us grow collectively and harmoniously. In this new relationship with nature, one embodied in pleasure, queer power, joy, kinship, one can find an intimacy that is erotic, generative and inclusive. It’s what Donna Haraway was alluding to, when she wrote in When Species Meet (2008): ‘To be in love means to be worldly, to be in connection with significant otherness and signifying others, on many scales, in layers of locals and globals, in ramifying webs.’ Or what Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson, in their introduction to Queer Ecologies (2010), refer to as being ‘disruptive’ of heteronormative approaches.

All these qualities mark Shepherd’s work.

With her attention to language, the limitless frame of her relationship with nature and her sensual perception, Shepherd’s writing is a model of commitment to queer ecology, avant la lettre. Shepherd explores the idea that emotional fulfilment can come from something other than heterosexual union, suggesting that it can instead be found in nature, in multiplicity, in desire and erotic kinship. Shepherd becomes ‘great’ in the mountains: she understands what it means to live with desire as she is, ‘Walking thus, hour after hour, the senses keyed.’ In this way, she writes, ‘The body is not made negligible, but paramount. Flesh is not annihilated but fulfilled. One is not bodiless, but essential body.’

I noticed this kind of kinship when I first listened to The Living Mountain over a few November afternoons in 2021, walking through the low hills of the Siskiyou Mountains, in southwestern Oregon. Each afternoon was a little different than the one before, the light rust with the shadows keeping their promises on the slopes, the walks becoming a necessary retreat from the entanglement and drama of politics at the time. Out walking with the other lovers of the hills, and the woodpeckers and tilted firs, there was, in Shepherd’s words, a silence ‘like a new element’, where I could go ‘beyond desire’ and walk ‘out of the body and into the mountain … [like] the starry saxifrage.’ I found the partnership of body and mountain exquisite, and unintentionally crafted by Shepherd as an ethic of queer ecological thinking – understated: yes, and yet representative of some greater truth we might adopt.

In thinking about why her book is a foundational text for the emergent field of queer ecology, I want to consider something I call a sensual momentum, which builds from queer ecological thinking and suggests that sensuality in our literature and our lives is not a limitation, but a freedom, wherein ‘Each sense heightened to its most exquisite awareness is in itself total experience.’ It is a thrust toward the aesthetic encounter, on the frontier of joy. Our longing for intimacy can be found only in the gleaming and showy brilliance of the relationship we form from our natural experience, as ‘when the body is keyed to its highest potential … [seeking] the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes’. Queer ecology, and this sensual momentum, commits itself to joy and desire; but is also a resistance practice, in opposing the oppressive elements of hierarchy, patriarchy, capitalism and heteronormativity.

For Shepherd, her method was a process of slow curation. She takes off her shoes in the mountains. She designs a love with the golden plover. She finds understanding in the miniature azalea that flourishes on granite, notices the ‘bounty of the earth’ in the saxifrage or sedum, and learns the art of gathering moss, writing: ‘my fingers learned to feel their way along each separate trail and side branch … I was learning my way in, through my own fingers, to the secret of growth.’

In this slim volume, Shepherd gives us a deep engagement from which pleasure and joy emanate; a clear sense that, within a mountain, over a life, a woman can and did discover supreme joy, outside of the oppressive and colonial structures that have come to define us. For her, this becomes a foundational way of being; for, as Shepherd writes, ‘as I penetrate more deeply into the mountain’s life, I penetrate also into my own … I am beyond desire.’ There is no need for anything, but the body shaped by the mountain in a queer and intimate kinship.