Google Glass was once billed as the next breakthrough in wearable tech: camera-equipped smart glasses that allowed the wearer to effortlessly take photos and videos or browse the internet via a display projected onto the lens. So what’s not to like? Well, they looked clunky, they cost $1,500, and above all, they creeped people out. ‘Glassholes’, as their wearers would come to be known, were essentially carrying around a piece of social surveillance equipment on the bridge of their nose, and people couldn’t stand it. After a couple of years and an attempt to curtail creepy usage, in 2015 Google discontinued retail sales.

New technologies have long provoked fears about the loss of privacy. The 15th century saw what the historian David Vincent called ‘epistolary anxiety’ – the fear that one’s personal correspondence will be read by others. The advent of the telephone brought similar concerns that operators were listening in on private calls. And in the digital age, privacy concerns have resurged. A Pew poll in 2019 found that 81 per cent of Americans think the risks posed by companies collecting their data outweigh any related benefits.

If we really care about our privacy, though, why do we share so much? We share our email and phone number with countless websites but wouldn’t give these details to a random person on the street. We share personal photos publicly on social media but wouldn’t dream of showing them to a room of strangers. Curiously, features of Google Glass that made people uncomfortable remain largely accepted in other forms: the panoptic gaze of CCTV captures our movements; social media companies scan masses of our public and private messages; and smart speakers record clips of our speech. Sometimes we have little choice: today, using your bank details online is all but unavoidable. But did you need to post that 12th gym selfie? It’s practically impossible to read each website’s privacy policy, but did you need to mindlessly hit ‘accept all cookies’ when a ‘reject all’ was right there? To explain these privacy inconsistencies, we need to take a look back. Way back.

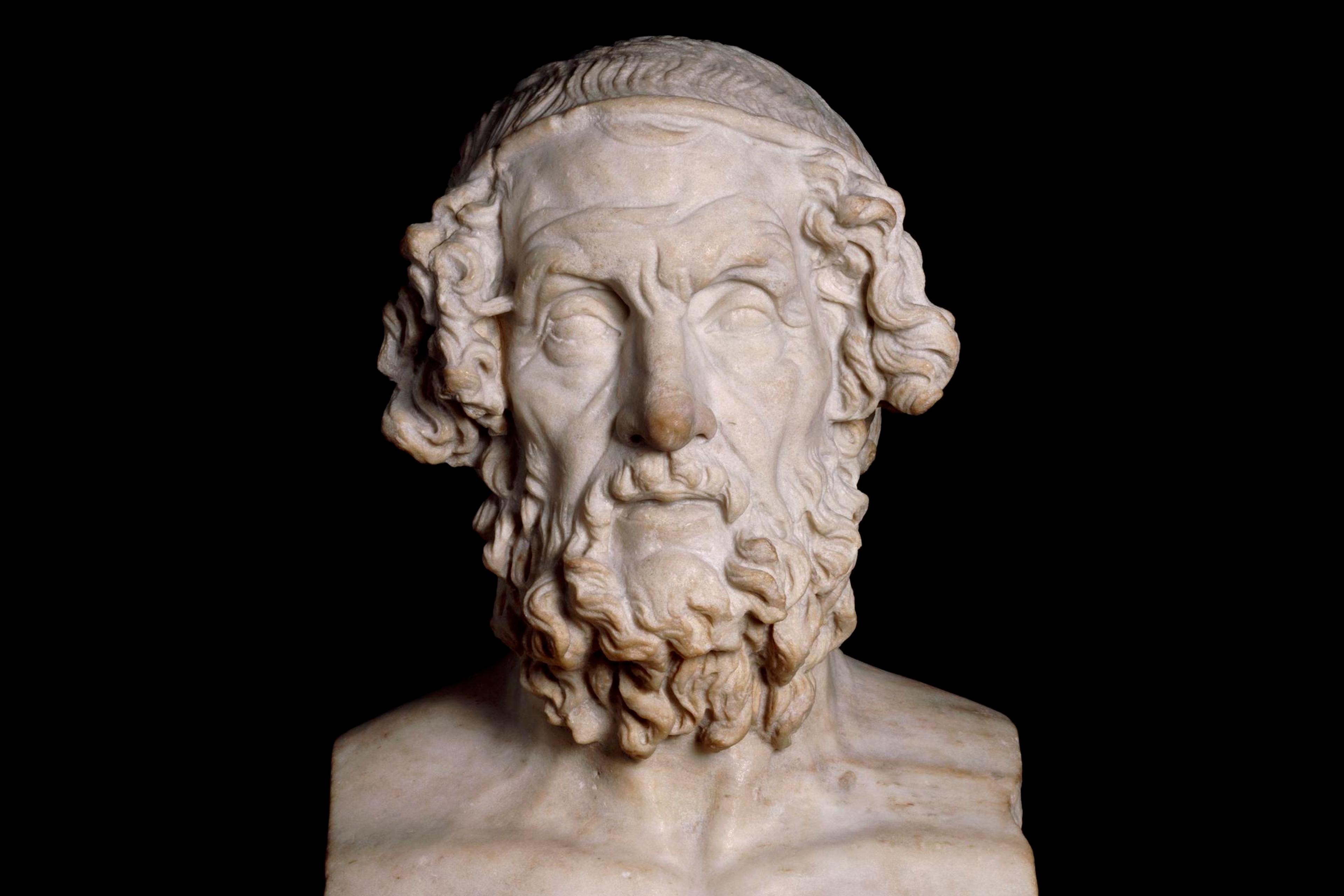

The evolutionary biologist E O Wilson once said of the source of human challenges in the 21st century that ‘we have palaeolithic emotions; medieval institutions; and god-like technology’. Homo sapiens spent the vast majority of its ancestral history in a palaeolithic environment that stayed relatively unchanged for hundreds of thousands of years, and then began a rapidly accelerating pace of change about 12,000 years ago: agriculture, writing, empires, the printing press, space flight, TikTok. But our brains, the product of the slow grind of evolution, don’t enjoy the same rapid upgrade cycle as our smartphones. The hardware between our ears today is largely the same model that roamed the African grasslands more than 100,000 years ago. And though it is extremely adept at navigating new environments, the human brain still bears the legacy of a psychology that was slowly etched into it by that palaeolithic environment. We retain emotional reactions that made evolutionary sense in that environment. But a rapidly changing technological environment inhabited by a relatively ancient brain creates a mismatch.

Evolutionary mismatches reflect previously adaptive traits that falter when environmental change outpaces what the slow plod of evolution can adjust to. For example, after they hatch, sea turtle hatchlings must make a night-time journey from the beach, where their eggs are laid, into the water. They have evolved to orient toward the lightest place, which has historically been in the direction of the ocean. However, human-made light pollution confounds this orienting reflex for baby turtles, leaving them crawling in circles or in the wrong direction until they die. A closer-to-home example of a mismatch is our own taste for fat and sugar. This is an adaptive trait for hunter-gatherers living half-starved in a constant search for calories. But as our environment has shifted to one of calorific abundance, a system tuned to enjoy calorie-rich foods has become the source of a constellation of obesity-related diseases. In a recent paper, we (along with co-author William Jettinghoff) argue that our intuitions about privacy are similarly mismatched to our current era.

Our concern for privacy has its evolutionary roots in the need to maintain boundaries between the self and others, for safety and security. The motivation for personal space and territoriality is a common phenomenon within the animal kingdom. Among humans, this concern about regulating physical access is complemented by one about regulating informational access. The language abilities, complex social lives and long memories of human beings made protecting our social reputations almost as important as protecting our physical bodies. Norms about sexual privacy, for instance, are common across cultures and time periods. Establishing basic seclusion for secret trysts would have allowed for all the carnal benefits without the unwelcome reputational scrutiny.

Since protection and seclusion must be balanced with interaction, our privacy concern is tuned to flexibly respond to cues in our environment, helping to determine when and what and with whom we share our physical space and personal information. We reflexively lower our voices when strange or hostile interlopers come within earshot. We experience an uneasy creepiness when someone peers over our shoulder. We viscerally feel the presence of a crowd and the public scrutiny that comes with it.

However, just as the turtles’ light-orienting reflex was confounded by the glow of urban settlements, so too have our privacy reactions been confounded by technology. Cameras and microphones – with their superhuman sensory abilities – were challenging enough. But the migration of so much of our lives online is arguably the largest environmental shift in our species’ history with regard to privacy. And our evolved privacy psychology has not caught up. Consider how most people respond to the presence of others when they are in a crowd. Humans use a host of social cues to regulate how much distance they keep between themselves and others. These include facial expression, gaze, vocal quality, posture and hand gestures. In a crowd, such cues can produce an anxiety-inducing cacophony. Moreover, our hair-trigger reputation-management system – critical to keeping us in good moral standing within our group – can drive us into a delirium of self-consciousness.

However, there is some wisdom in this anxiety. Looking into the whites of another’s eyes anchors us within the social milieu, along with all of its attendant norms and expectations. As a result, we tread carefully. Our private thoughts generally remain just that – private, conveyed only to small, trusted groups or confined to our own minds. But as ‘social networks’ suddenly switched from being small, familiar, in-person groupings to online social media platforms connecting millions of users, things changed. Untethered from recognisable social cues such as crowding and proximity, thoughts better left for a select few found their way in front of a much wider array of people, many of whom do not have our best interests at heart. Online we can feel alone and untouchable when we are neither.

Consider, too, our intuitions about what belongs to whom. Ownership can be complicated from a legal perspective but, psychologically, it is readily inferred from an early age (as anyone with young children will have realised). This is achieved through a set of heuristics that provide an intuitive ‘folk psychology’ of ownership. First possession (who first possessed an object), labour investment (who made or modified an object), and object history (information about past transfer of ownership) are all cues that people reflexively use in attributing the ownership of physical things – and consequently, the right to open, inspect or enter them.

The digital space befuddles these ancient ownership intuitions. For example, as the apps on our phone record our geolocation data, how do we discern ownership of that data based on first possession? Are we the first possessor of the data, or is the app? How about when we post on Instagram – do we attribute labour to Instagram for providing the platform, or to ourselves for providing the content? And what about our personal data on Facebook – do we even understand the transfer of ownership that we ‘agreed’ to? As the digital world obscures the cues that guide our ownership psychology, we are often left not knowing what’s ours, and whether we ought to then protect it.

What practical use is there in understanding the arcane evolutionary origins of privacy concern? After all, contemporary threats to privacy are widely known and discussed. From Cambridge Analytica improperly obtaining millions of Facebook users’ personal data, to hackers stealing customers’ personal details from the adultery website Ashley Madison, to the sweeping, clandestine surveillance of telecommunications by the US National Security Agency or more recently by private companies such as the Israeli NSO group, examples of modern privacy scandals abound. And yes, in the cold light of abstract thought, we recognise these threats. But we don’t feel them in the way we do more traditional threats to privacy. Stripped of the social cues that tend to ring our emotional alarm bells, the online environment elicits a muted response. The power of emotions evolved to provide enough of the motivational oomph to rally us to action. Using the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s memorable metaphor, our abstract recognition of privacy threats moves the (rational) rider, but not the (emotional) elephant.

Importantly, we are not calling for privacy absolutism. Like all values, the desire for privacy needs to be balanced against other values, such as public safety and economic efficiency. Sorting out public policy and individual behaviours should involve a reasonable balancing of the costs and benefits. The problem is that, with our intuitions mismatched to the actual consequences of various privacy invasions, any decisions based on those intuitions – rather than on sober, dispassionate expertise – become untethered from the costs. Left to fend for ourselves in the moment, we might under-react to especially unsexy threats, or overreact to especially evocative ones. Moreover, governments and corporations with interests in collecting our information can placate us by easing our emotional reactions, while leaving the actual threats to our civil liberties unaddressed.

This brings us back to the issues raised by Google Glass. Some people are once again predicting smart glasses to be the next big thing in wearable tech. And while Apple has reportedly decided to ditch unpopular features such as the front-facing camera for its own rumoured product, other competitors are simply embedding their cameras within a less obvious, more fashionable design – out of sight and out of mind. Either way, as smart devices continue to look better, do more and cost less, consumers will have to decide whether the associated privacy trade-offs are worth it. Our evolved privacy psychology is no longer up to the job of intuitively guiding such decisions. As consumers, then, we need to be mindful of our shortcomings in this regard, demanding more privacy protection from companies and a little more circumspection from ourselves.