What the Romans call amor permeates Ovid’s epic masterpiece, the Metamorphoses. Such amor, traditionally translated into English as ‘love’, has two sides. One is violent, leading to abuse and domination. This is the amor brought into the cosmos by Cupid’s arrows when he pierces Apollo and Daphne, causing the former to feel intense attraction and the latter equally intense repulsion. Such amor regularly ends in rape or attempted rape, followed by transformation. To us, this does not look like love at all, but, to the Romans, amor was often associated with violence and conquest, its primary metaphors ones of suffering – burning, wounding, disease, and war. This amor is the driving force of lovers and tyrants alike. In the Metamorphoses, it arises especially among the gods, who wield it against those lower on the cosmic hierarchy, such as nymphs and humans. Such destructive passion fits well into Ovid’s larger interest in abusive power and how it transforms its victims, denying them bodily autonomy.

Yet, there is another type of amor in Ovid’s epic, that of mutual love, which must be read against its brutal counterpart. This love, too, is transformative, but mutually so. Reciprocity sits at the heart of such amor, which is independent of Cupid’s arrows. This amor does not burst forth in a fit of violence but develops through familiarity. Such love, arising usually among non-divine characters, is defiant in its contrast with the world of heaven. Though the human world can and does imitate the worst crimes of the gods, as in Tereus’ rape of Philomela, it is also able to transcend such violence.

The epic’s first tale of amor is usually considered to be that of Apollo and Daphne, in which the nymph transforms into a laurel tree to escape the god’s rape. Ovid even introduces the tale with the words primus amor, ‘first love’, setting the stage for the many sexually violent love stories to come. Yet, prior to this tale, we meet Deucalion and Pyrrha, a married couple who act as a powerful foil for Apollo’s destructive passion. These are the sole survivors of the flood sent by Jupiter (Jove) to wipe out the human race, and together they restore humanity. Ovid emphasises their mutuality through parallel language (all translations are my own):

Jove sees the pools engulfing all the world

and how from thousands just one man survives

and how from thousands just one woman too –

both innocent, both worshippers of gods.

This tale gives us only a brief glimpse into a marriage, yet it reveals a connection forged over years – as Deucalion puts it, the two are ‘joined’ through family, through marriage, and through crisis. They now desire a shared fate. ‘If the sea held you,’ Deucalion tells Pyrrha, ‘I’d follow you so it could hold me too.’ Whereas Apollo and Daphne are never the joint subject of any verb, Deucalion and Pyrrha together perform more than 20 actions as they work toward renewal rather than destruction. Their love is humanising, quite literally – they create humans from rock. This strikes a powerful contrast with the dehumanising love of Apollo, which leads Daphne to become an object.

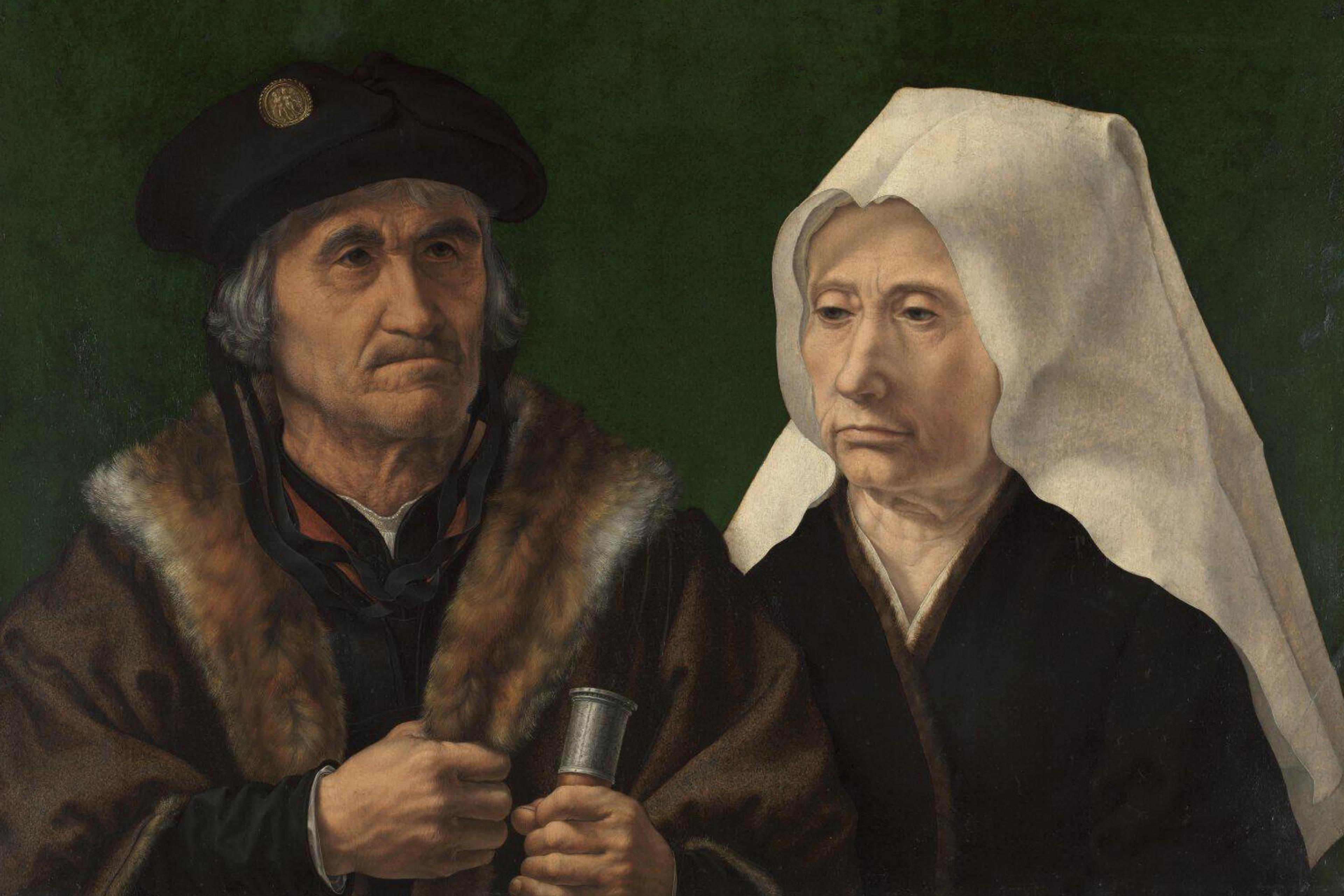

The love between Deucalion and Pyrrha anticipates some of the epic’s most moving tales, such as that of Baucis and Philemon, the poor old couple who, unlike their neighbours, offer hospitality to the disguised Jupiter and Mercury, and are themselves saved from the gods’ vengeful flood. Their easy choreography while cooking in their simple kitchen speaks to a longstanding intimacy, and the language Ovid uses to describe them sets them apart from hierarchical power: ‘It makes no difference if you ask for slaves / or masters there. The house consists of two, / and each alike gives orders and obeys.’ Equality is the soil in which mutual love takes root.

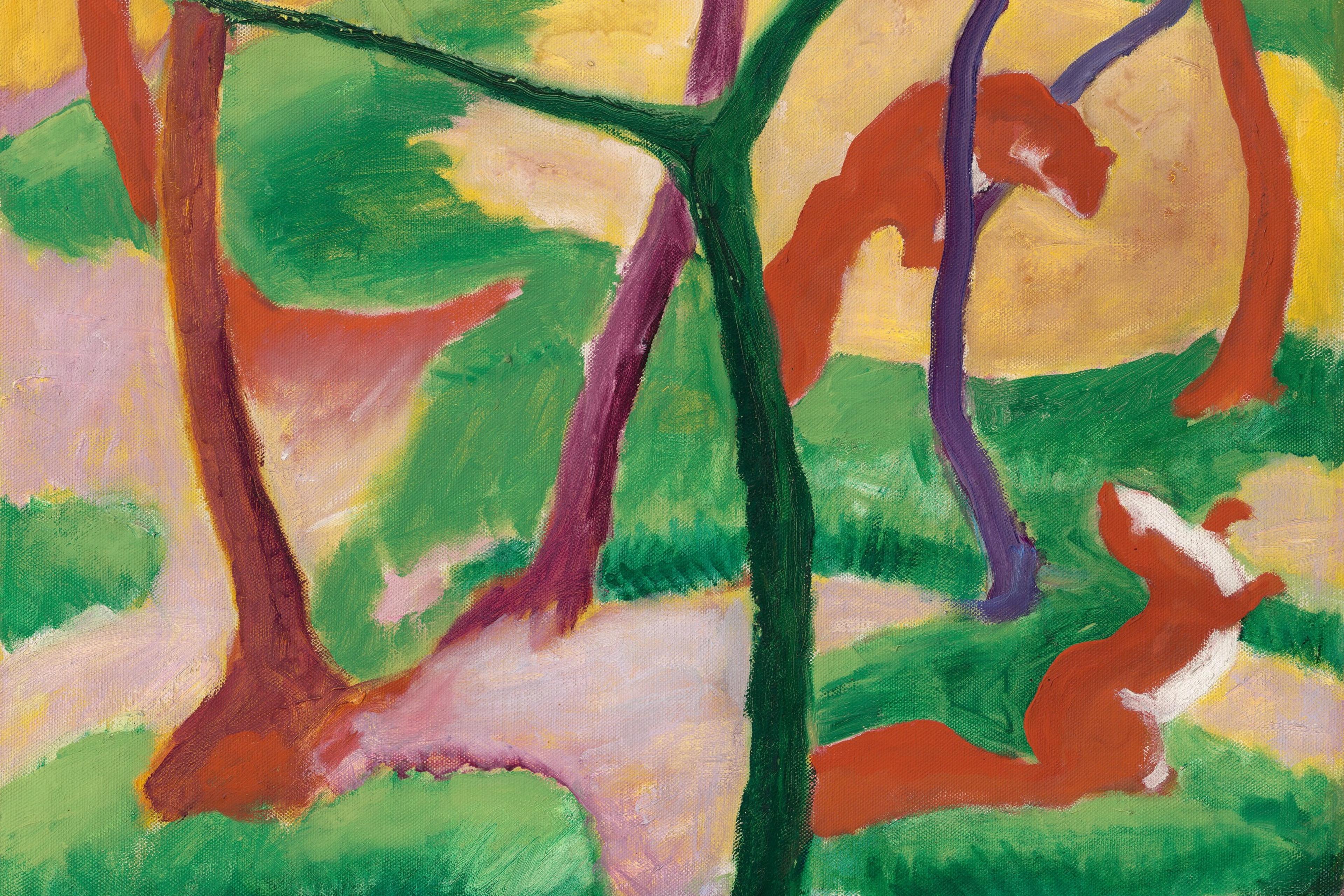

As a reward, Jupiter and Mercury grant Baucis and Philemon a wish. The two consult and issue a ‘joint decision’ to remain in their home, now transformed into a temple. Like Deucalion and Pyrrha, they desire a shared fate, one that continues the ‘harmony’ that has characterised their marriage. This shared fate comes in the form of metamorphosis as the two simultaneously become trees, a linden and an oak. Their final utterances are likewise shared:

They spoke, while they still could, requited words.

‘Goodbye, my spouse,’ they said at once. At once,

bark sealed their covered mouths.

Though a character named Lelex tells this story to celebrate the piety of Baucis and Philemon, their requited love comes as something of a rebuke of the gods, among whom there exists no equally poignant example of devotion.

Ovid shows us such mutual love in young and old alike. His best-known young lovers are Pyramus and Thisbe, who would later become the inspiration for William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Forbidden by their parents to marry, they converse through a cracked wall shared by their homes. The one-sided, objectifying gaze that often precedes violent rape becomes impossible here as the lovers must speak, not look. Familiarity precedes love, yet passion still burns hot – their ‘spellbound minds burn equally’. A shared fate ultimately comes in the form of a double suicide, with the lovers’ ashes resting in the same urn. This tale, too, is defiant, told by one of the Minyads, sisters who reject the god Bacchus. The agency and reciprocal passion of Pyramus and Thisbe diverge sharply from the mania Bacchus inflicts on his followers, which makes them lose themselves completely.

Ovid resists a simplistic, heterosexual paradigm for mutual love. In one particularly moving tale, Iphis is born female but raised as a boy to escape being killed. Falling mutually in love with a girl named Ianthe and becoming betrothed to her, Iphis despairs of being unable to penetrate her sexually on their wedding night. Due to the Romans’ seeming inability to imagine sex without penetration, the goddess Isis transforms Iphis to have a phallus prior to the wedding. It is not clear if Iphis ultimately identifies as a man or a woman, yet the queer desire that blooms between Iphis and Ianthe seems especially conducive to mutual love. There is no power disparity, no drive to dominate, as in so many Ovidian tales of heterosexual passion: ‘love touched / their youthful hearts, dealing them equal wounds.’ This is one of the few tales that ends with a joyous wedding.

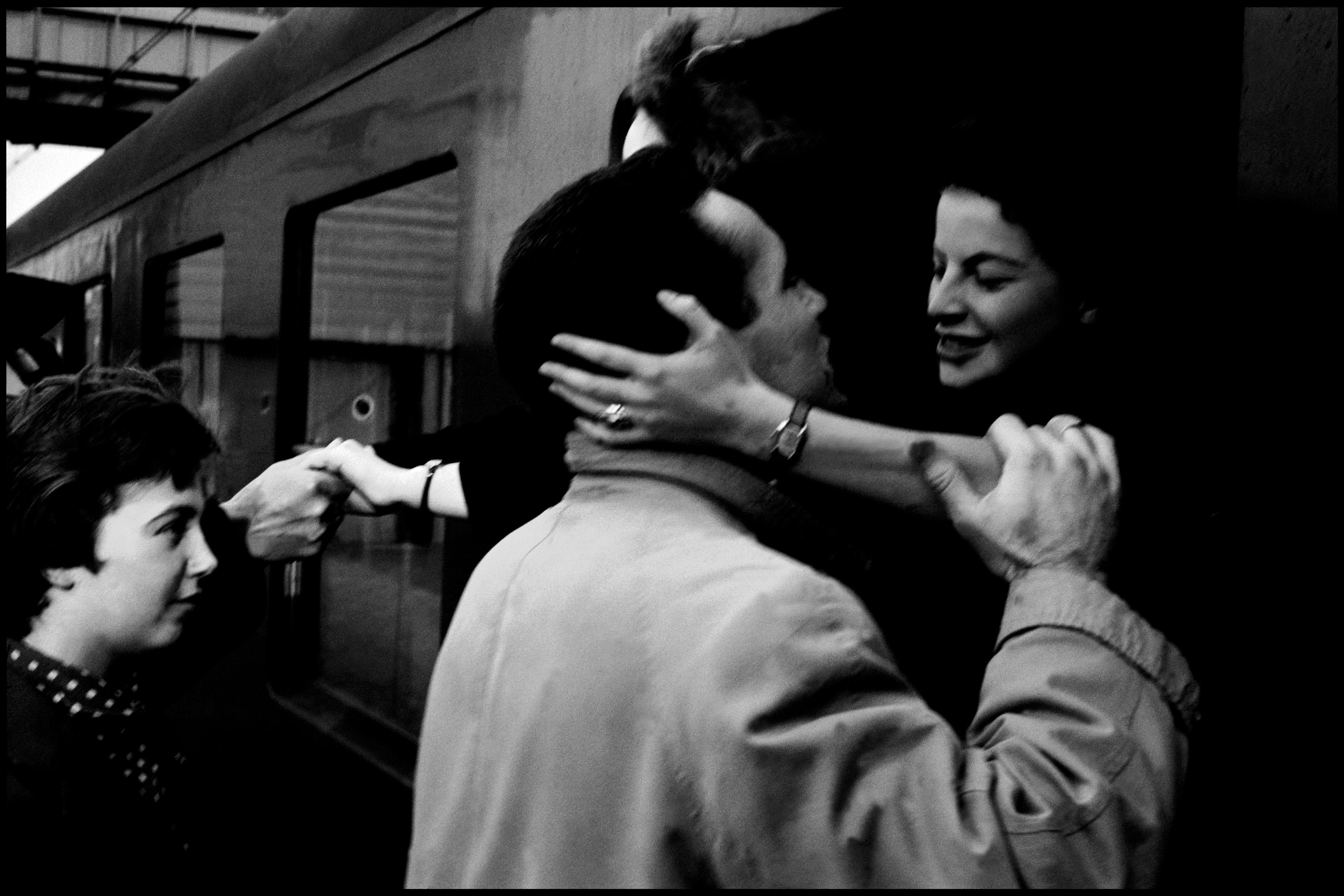

Ovid’s contemporary poets, such as Propertius, treat marriage as being largely in conflict with love, yet, for Ovid, consensual matrimony becomes a potent site of shared amor. In many ways, Ovid helps set the stage for the later ideal of marriage as the culmination of romantic love. My own favourite of Ovid’s married couples is Alcyone and Ceyx, queen and king of Trachis. Their love, too, is passionately mutual: ‘he burned / no less than she.’ When Ceyx must take a sea voyage, the two watch each other as his ship sails away:

Alcyone lifts up her sobbing eyes

and sees her husband standing on the stern

signalling with a wave. She signals back.

As land recedes and her eye cannot spot

his face, her vision trails his fleeing ship

as long as possible.

While apart, Alcyone continues to gaze at Ceyx in her mind’s eye, and he does likewise. Wrecked in a storm at sea, he directs his line of sight her way: ‘he’d like his final gaze to look toward home.’ Whereas the voyeuristic male gaze dominates its object, as in the tale of Apollo and Daphne, this double gaze between Alcyone and Ceyx communicates shared desire, offering a mirror reflection of the other’s love.

After Ceyx’s death, this gaze repeats itself as Alcyone watches his corpse wash ashore. Determined to die too, she leaps into the waves, becoming a halcyon. In the epic’s only example of a human successfully being brought back from death, Ceyx, too, transforms into a bird, a metamorphosis that makes their love eternal: ‘Then too their love remained, sustained / by their shared fate. The marriage of those birds / abides intact.’

Whereas Alcyone’s love can reanimate her lost husband, another Ovidian lover, Orpheus, fails to bring his beloved Eurydice back to life. After his new bride dies, the singer descends into the Underworld, determined to restore her. He initially succeeds, with Pluto and Persephone returning Eurydice under one condition: he cannot look back at her until both have re-emerged into the upper air. This is, in many ways, a test of what kind of lover Orpheus is. Can he, like Pyramus and Thisbe, love without looking? Can he, like Ceyx or Alcyone, gaze only in his mind’s eye? He famously cannot: ‘Intent / on seeing her, the lover turned his eyes.’ He loses Eurydice a second time, succumbing in his victory to a one-sided desire that cannot restore her.

It is not until his own death that he and Eurydice can be reunited:

They stroll, now side by side, now as he follows,

now as he leads. And Orpheus in safety

can turn and look at his Eurydice.

Both kinds of amor exist within this tale, and it is only when Orpheus and Eurydice love on equal terms, with neither determined to triumph over the other, that mutual amor can win out.

It is not entirely clear which type of love ultimately prevails in the Metamorphoses. The tale of Pomona and Vertumnus, Ovid’s final tale of passion (ultimus ardor), grants a victory, though a tentative one, to mutual amor. In this tale, the nymph Pomona is hostile to sexual love and locks herself away inside her garden walls. The young Vertumnus, a master of disguise, dons a number of costumes to get near her ‘so he can see her beauty and feel joy’.

Vertumnus’ amor seems destined to be unrequited and violent, like that of Apollo. He is indeed fully prepared to rape Pomona, until he appears to her undisguised, and his beauty becomes the object of her mutual gaze:

He readies force but needs no force – the nymph,

seized by the god’s good looks, felt equal wounds.

It is hard to know whether this is a story of rape or of mutual love – it is best read both as a rejection of violent amor and as a demonstration of its continuing threat. Perhaps the most disquieting aspect of Ovidian myth is that both types of love can exist within the same person.

As with much else, Ovid lets both sides of amor stand juxtaposed. Yet, the pronounced theme of mutual love undermines any attempt to cast Ovid as a simple poet of rape, who delights in recounting the trauma of victims. Ovid’s mutual lovers, despite the abusive violence of their world, are able to grasp what agency they can through love, raising a defiant fist toward anyone who would forcefully take what is best when given freely.