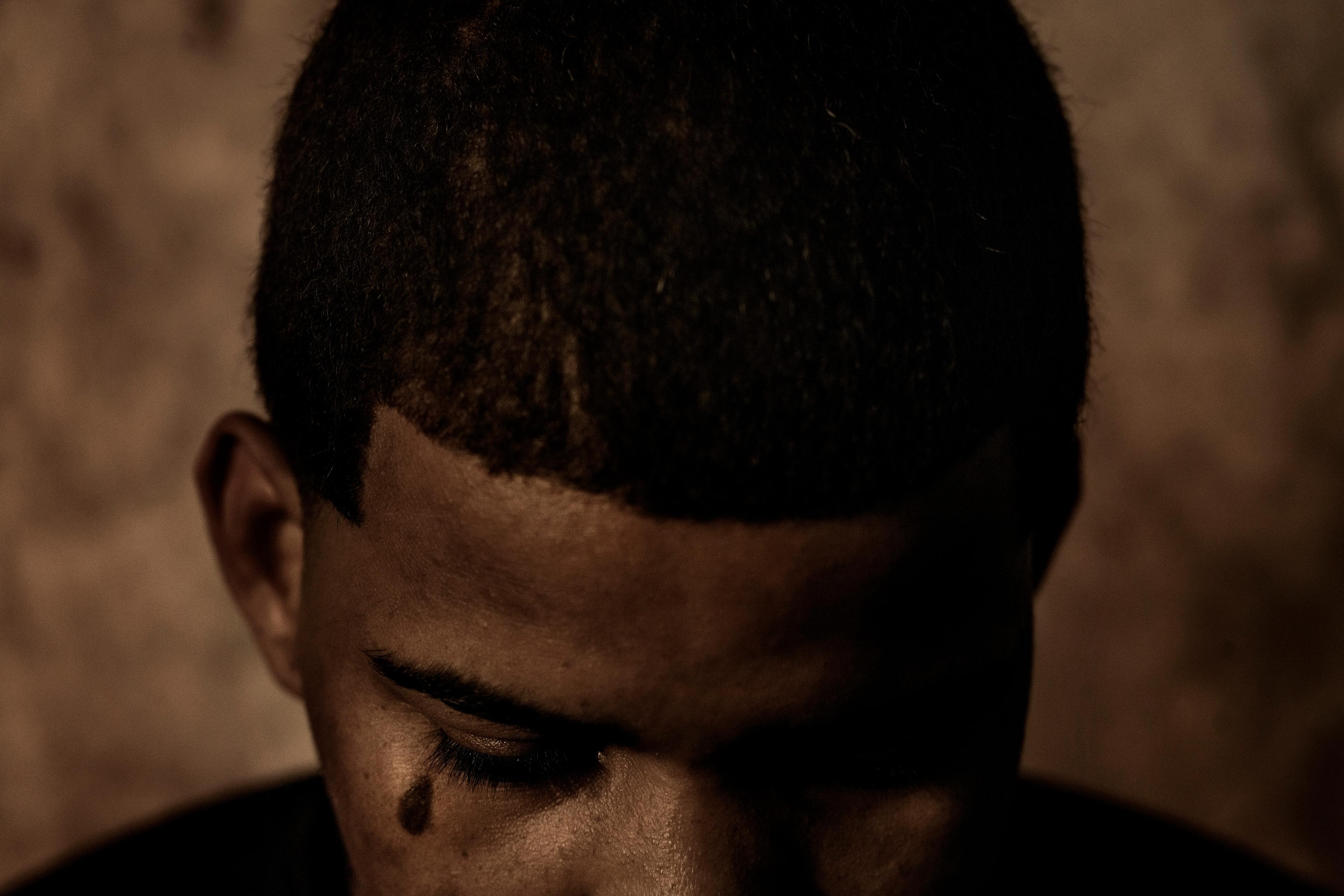

It’s the lost time I miss the most. Time I will never get back. It is the minutes I have spent in racist, dangerous, time-sensitive situations, desperately sifting through choices to find the one that will keep me safe and my dignity intact. It’s the hours I have spent thinking of experiences with racism – both mine and my ancestors’ – and trying to plan a future with fewer of these experiences. And, all the while, I know that I’m wasting my time because the game is rigged.

There are no right choices. I live my life as a Black American woman – a woman who is subject to time that fuses the past to the present, collapsing the future into an endless repetition of the past. This boundless, embodied time is a result of experiences with racism – a race-based time that observes no substantive boundary between past, present and future. We inherited it from our ancestors, live it in the present, and we pass it on to the next generation.

In response to this current moment, people who otherwise haven’t thought much about what it’s like to be Black in the United States are now educating themselves about the ways that racism affects Black life and the choices Black people are forced to make. There are countless reading lists, articles, blogs, etc aimed at making the invisible more visible. But there is more to Blacks’ experiences than the external ways that racism shapes our lives. It also poisons our internal sense of time and how we live out our lives in that time.

Like everyone else, Black people live under the confines of neutral, standard time. We’ve all experienced moments in our lives when time seems to speed up, slow down or stand still, but there’s no escaping the fact that a minute is 60 seconds; that there are 60 minutes in an hour. Time is indifferent to our experiences and concerns – it doesn’t care that we want more or less of it. It’s a cliché, but no less a sober fact of life, that time waits for no one.

For those of us who, as a people, carry our own present experiences with racism and our ancestors’ past experiences of racism in our bodies, the experience of living in time is warped. The lived, embodied reality leaves us subject to another kind of time altogether. Far from being neutral or indifferent, this kind of time mocks the neat boundaries we attempt to place on history, collapsing them into one another. ‘Black time’ is not only temporal. It is material. It lives in our hearts leading to increased risk of heart disease. It lives in our lungs increasing the risk of asthma. And it lives in Black women’s wombs increasing the chances of high-risk labour and underweight newborns. The past infuses the present and imprisons the future.

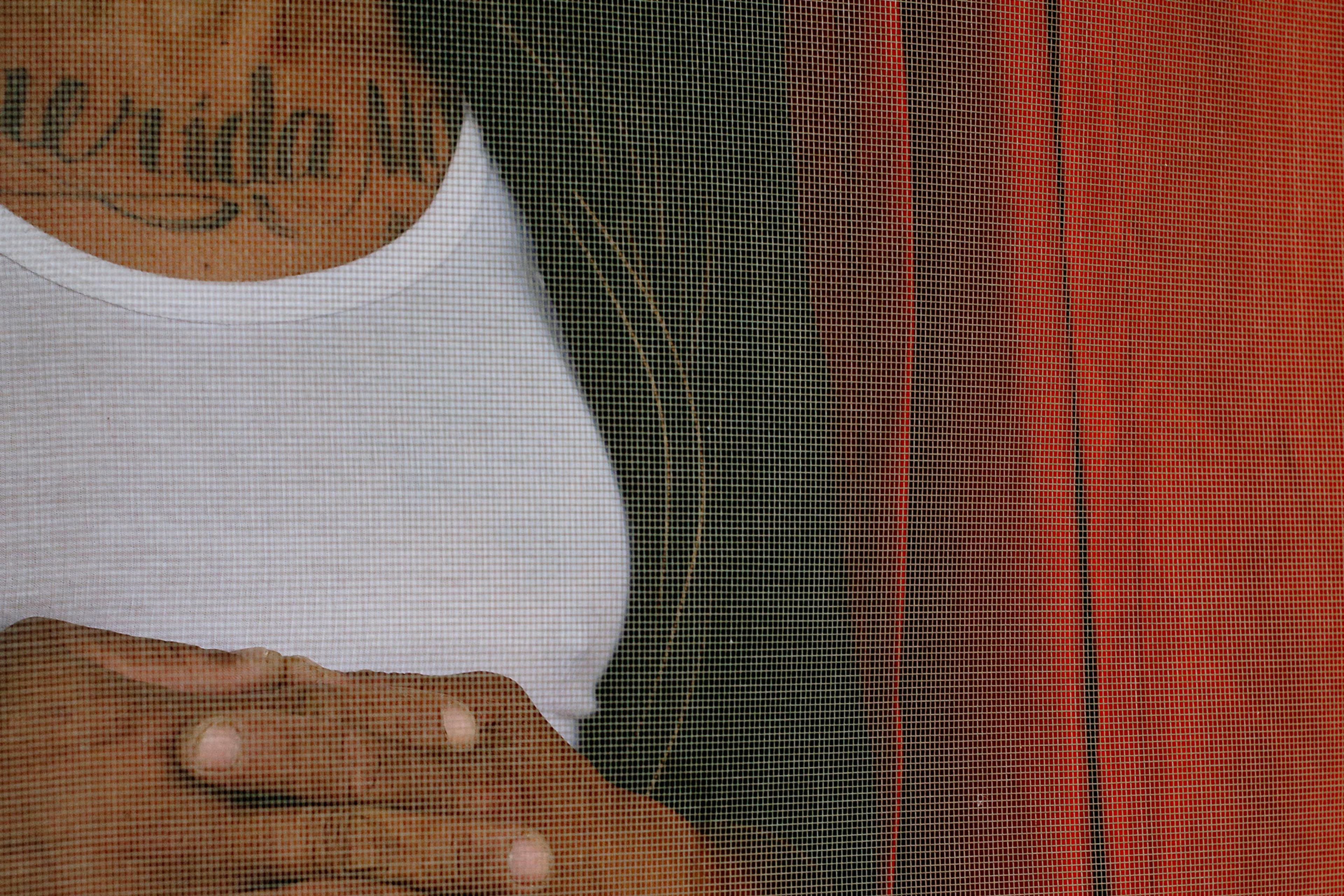

Scientists discovered years ago that experiencing racism affects the body at the cellular level. Arline Geronimus, professor of health behaviour and health education at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, made a connection between social disadvantage and the poor health outcomes she observed in Black girls and women, regardless of socioeconomic class or ‘healthy’ behaviours. The human body evolved to respond to perceived danger by stimulating a cortisol cascade. This ancient response taxes the body as it prepares us to fight or flee, but it’s supposed to be short-lived. If it’s chronically stimulated by happening too frequently or continuing for too long, it causes damage. Geronimus found that hardship and chronic threats – such as witnessing racialised police brutality, or struggling to make ends meet on a minimum-wage job – stimulates the fight-or-flight response. For those living under disadvantage, Geronimus notes, that fight-or-flight response might never abate: ‘It’s like facing tigers coming from several directions every day.’ The result of facing those tigers daily is that our health declines disproportionately with age, as the damage of repeated or sustained cortisol cascades is compounded over time.

Compounded over how much time? Centuries – beginning with the first ship of enslaved people brought to these shores in 1619. As long as racism shows no signs of abating – and it doesn’t – the rational mind anticipates the assault, and the body’s sympathetic nervous system plans for it by preparing us to fight or flee the terror we haven’t been able to escape for centuries. Four hundred years later, Black people continue to experience as well as anticipate daily assaults on their person and dignity. We have every reason to expect more in the future. And we do so in bodies that carry the cumulative trauma of a racist past.

Blacks and whites don’t, in general, share the same bodily, intimate relationship with time. I suspect this explains why whites often fail to appreciate the close proximity of slavery in our nation’s history. ‘Why are we still talking about it?’ they ask. It was abolished long ago (and, by the way, their families never owned slaves, there are poor whites, they worked hard for what they have, etc). We point to the continuing legacy of slavery. The Black/white wealth chasm, the mass incarceration of Black men, the Black women and girls kicked out of schools, and the invisibility of those Black women who have been felled by police officers’ guns. If they remain unconvinced of slavery’s enduring legacy and proximity, we can remind them of Cudjoe Lewis, one of the last enslaved people brought to the US. His life began in 1841 and ended in 1935. There are Americans living now who walked this Earth when he did.

White people have a chronologically simpler, less intimate relationship to the US’ slaveholding past. Chronologically simpler because the abolition of slavery, the end of Jim Crow, the passage of the Civil Rights Act, and the election of the first Black president appear to demonstrate the linear march of Black progress. Less intimate because past and present experiences of anti-Black racism are not in their very cell function, causing them chronic health problems that dramatically shorten life spans. For Black people, the present is infused with the horror of daily reminders, preparation for, and experiences of racist events from the distant and recent past repeated in the present.

Racism has broadened Black time to an amorphous always and everywhere.

What are the boundaries of ‘the past’ when pregnant Black women pass both their own and the inherited ancestral trauma of experiencing degradation, abuse and indifference to their unborn? What is the ‘back then’ when the cumulative effects of simply anticipating racism makes labour risky and increases the chance of an underweight newborn in the present? Racism and its enduring structures rob words such as ‘past’, ‘back then’ and ‘the future’ of any real meaning. If the spectre of racial violence is not present at the forefront of our minds, it’s lurking in the background and in our cells, hitching a ride to the next generation, holding us hostage in real time.

As a recent transplant to the Deep South from the Northeastern US, my only exposure to Black Southern life comes from books and those few family visits made when I was a child. To survive here, I have no choice but to spend time adjusting to this space, reflecting on the experiences of my ancestors as I carry them within my body. Most certainly, in time, I will sustain more trauma that will find its way into the cells of my body. I will spend so many minutes and hours wondering what past trauma my daughter has inherited from me that she now carries within her. This is how I will spend my time. And I will never get it back.