I took a risk when I cast Danni – lithe, blithe, and in her mid-20s – to play Juliet in an expensive, modern-dress production. On opening night, the first of 30 performances, she expressed Juliet’s character with a stunning presentation that earned her a standing ovation. On the second night, her performance showed signs of deterioration. By the third night, she had lost Juliet: her performance had become a recitation of words, a common experience for untrained actors.

Danni (not her real name) knew this – actors always know. She called the next morning asking me if she could quit. I had woken early expecting her call because Danni is a professional, a literary scholar. She knows William Shakespeare’s plays and has had articles about his imagery published. She felt humiliated. I suggested we workshop the text later the same day. She agreed; we met in the afternoon, and I decided to introduce her to the ideas of Constantin Stanislavski (1863-1938) – but not his method, for which he is best-known.

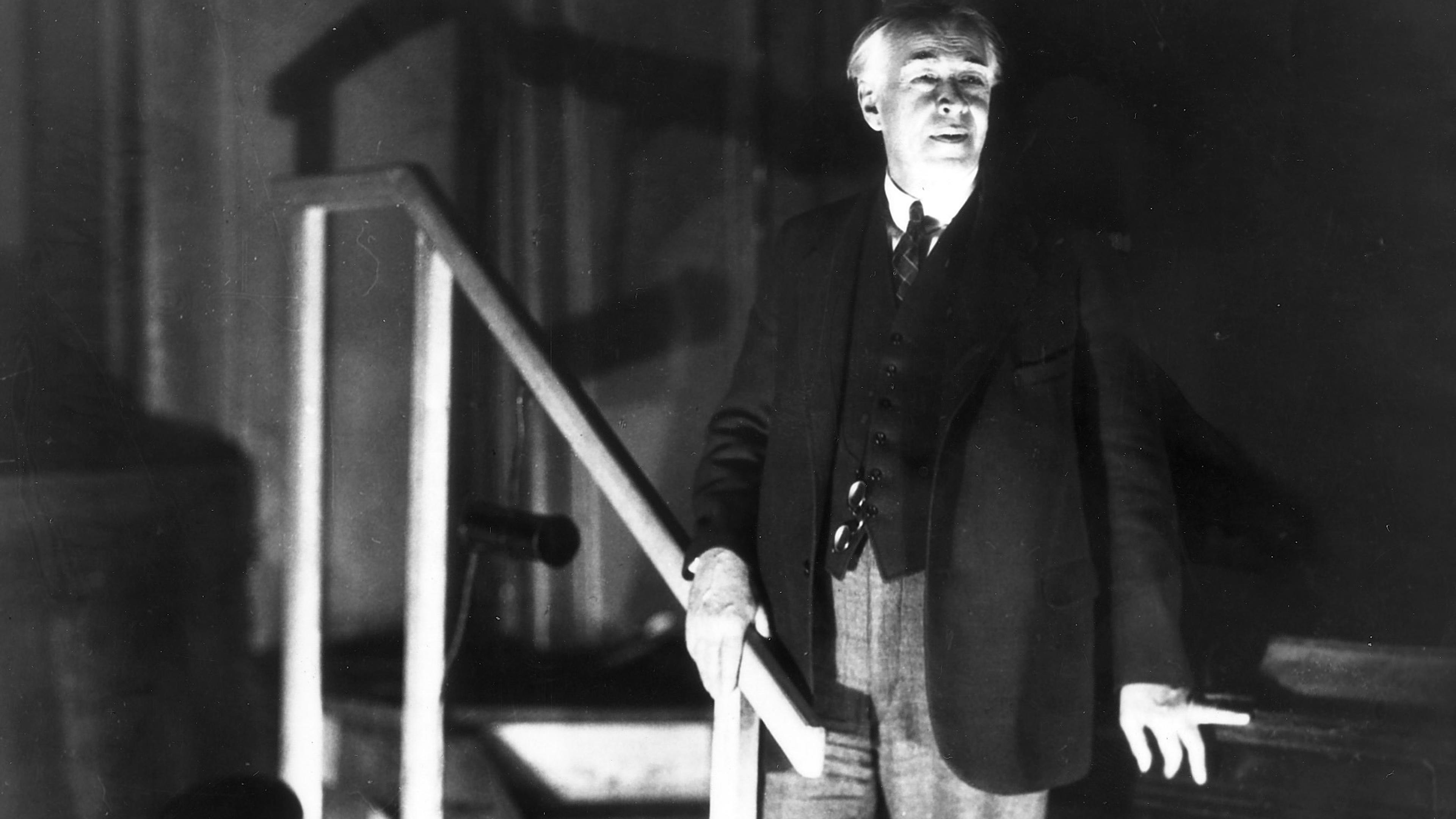

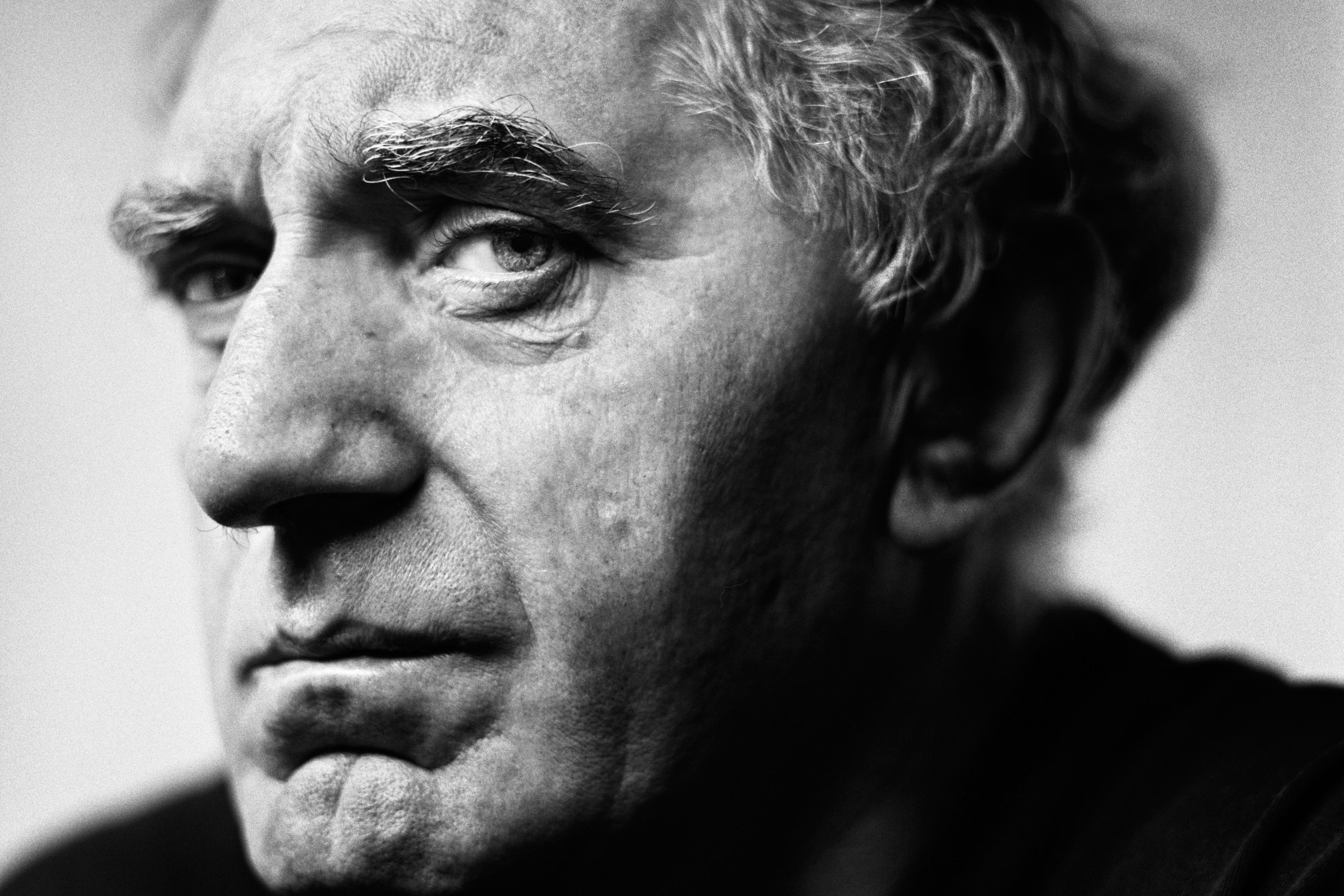

In three widely influential books, Stanislavski taught actors to search their lives for experience of feelings related to their characters, and then to use the material to help them perform with authenticity. They were to plumb past trauma, joy, grief, euphoria, and relive those feeling states each night on the stage. Later, Lee Strasberg (1901-82) formed the Actors Studio in New York, applying Stanislavski’s early system, to develop what we know as ‘the method’. He taught actors to immerse themselves in their ‘affective memories’ of past experiences to find emotional truth and bring their characters to life.

But by 1938, Stanislavski had turned away from this method to explore a new idea, which advised actors to study the text and articulate what their character struggles to achieve – the character’s ‘objective’ – throughout the whole play, in every scene, and then to simply note what the character should feel along the way. Thus, an angry Hamlet who struggles to avenge his father might produce a different performance from a cool, calm Hamlet who plots to win the crown. Instead of reawakening feelings from their past lives, Stanislavski’s actors struggled to achieve a character’s objectives and decide what the character should feel in each scene. Stanislavski’s new technique required a closer study of the text. That proved to be psychologically healthier for actors, and a more reliable way to behave with emotional authenticity from moment to moment on stage, which is the actor’s fundamental task.

Anatoli Romashin (1931-2000), the Russian actor, professor and former head of the acting programme at the Institute of Cinematography in Moscow, once told me how Stanislavski’s new technique challenged his actors to study the text more closely, to create performances that amazed audiences at the Moscow Art Theatre. The new approach delivered more consistent and authentic behaviour on stage than ever before. Stanislavski changed the art of acting, and then changed it again. His contribution is unprecedented in the history of performance.

Stanislavski’s new system freed Danni because she didn’t want to continually plumb her past life for memories of grief and hurt, and who could blame her? Actors don’t need to live through their actual grief and pain again and again. Instead, when they find, articulate and work with the motives driving their characters, they play with astonishing emotional truthfulness.

With that in mind, Danni and I began to workshop Juliet. We played with one line from the balcony scene: ‘Do not swear at all;/ Or, if thou wilt, swear by thy gracious self …’ Danni decided that Juliet felt affection for Romeo and struggled to persuade him to speak from his heart. Thus, Danni produced an authentic, useful reading. It worked, but I proposed that she play with contrary feelings and objectives, that she discover the text by playing with it. I suggested that Juliet felt awkward and wanted to get rid of Romeo. Danni protested, but tried, and found that she could give new meaning to the words with Stanislavski’s technique. Now they seemed to mean Don’t tell me anything, and if you do, it’ll be lies. Think of the words ‘I love you’ – what do they mean? It depends on what you want them to mean.

By playing with text, actors become players who play with plays. Danni, too, learned that she could give meaning to words by noting her character’s feelings and articulating what Juliet struggles for. We played with other lines, feeling states and actions. We workshopped during the run with different scenes. In the second week, Danni created an emotionally powerful, consistent and surprising Juliet because she used her moment-to-moment self to give life to the words on the page.

One day, Danni declared that finding the role of Juliet in herself was the same as developing her roles in real life. As an assistant professor of English, she had to articulate her objective (to challenge?) and feeling state (confidence?) before meeting a class. Like Juliet, her role as professor was one that she could play with her own resources. Danni saw through the idea that actors lose themselves to become a character as false. Actors create characters that don’t exist until created with the actor’s genuine personal resources.

Three insights emerged for Danni. First, she dropped the misconception that actors become another person on stage – an impossibility. Any attempt to become someone else leads to pretence. Instead, the best actors can play and create characters using their own resources.

Danni also realised the difference between a scholarly approach to text and the actor’s close study of internal actions driving external behaviour and feeling states. Actors deal in action. To create drama, they need to know what their characters struggle to do. What drives Hamlet? Revenge or getting the throne? Different intentions will play out in behaviours that create various performances using the same words. Stanislavski insisted that actors analyse sections (or beats) in every scene and every act until they have articulated a linked chain of actions from beginning to end.

Third and crucially, Danni began to see dramatic dialogue from the perspective of human life. When Jacques, in As You Like It, says: ‘All the world’s a stage,/ And all the men and women merely players;/ They have their exits and their entrances,’ it’s easy to see the line as a metaphor. But he states a fact. When we ask what Jacques is struggling to do, I’d say he wants to convince us that we are all players. We know that human beings – by imitating – learn to play roles in society and thus earn an identity. Evolution gifted us with a drive to shape our behaviour so that we and our group will succeed. We all become players who know our ‘exits and entrances’.

Of course, needing to play the same social role all the time can lead to problems, a twist not often taught by religious or national groups threatened by this kind of shift. Societies endure when members believe that their social roles endow them with identity, which explains why some consider gender transition a threat.

At one extreme, people might embrace racial or tribal roles that validate attacks on those not part of the group. When we believe, usually in our mid-20s, that we need our social role, and that it describes all that we are, we have fallen into an evolutionary trap. We’re more than that social identity. Actors drop their roles when the curtain falls. If they didn’t, once an actor took Hamlet home for dinner, we’d think him mad. Yet we tend to think our social roles define us at dinner and everywhere else.

As Stanislavski suggests, we are more than the social roles we play. Were I raised in the tribal areas of Pakistan, I could take my tribal identity to Los Angeles, learn to let go of it, and play an LA role. Neither would define me because I am more than the parts I play.

The arts of acting and living, as Stanislavski realised, require that we find the roles we play within ourselves, interpreting and articulating psychological needs as we go. In his late-life revision, Stanislavski overcame, for the first time in history, the notion that acting is entirely intuitive. The paradox is that the art of acting requires the mastery of technique to consistently create authentic performance. His insight about acting is rooted in the fact that our nature always requires human beings to pursue objectives in real life. The difference between acting and living is that artful actors let go of their character’s needs at the end of a performance.

Danni, by the way, went on to become a successful university scholar and teacher but never returned to the stage. She still plays a role or two every day at home, on the street, or in her department.