At 7am, I left my apartment and walked quickly towards the rising sun. Golden rays shone down at a distance on the land of forgotten warriors, the blue sky a roof of hope overhead. It was winter, and my breath steamed from the corners of my face mask as I walked, worn under my black hijab and scarf.

I turned a corner and the blinding sun ducked behind a building. The Taliban checkpoint was near the roundabout. It was just one of many that had sprung up all over Kabul, impossible to avoid when you walked through the city. Here, the men were displaying their weapons. Their uniforms were mismatched – one had an army jacket, another didn’t; one wore trousers while another was in traditional dress, with a shalwar kamees and turban. They all had long beards, oily hair and stern expressions.

I passed close by. The area was encircled by large cement barriers, leftovers from the previous government. Now the men used them as resting places for thermoses, teacups, wet clothes left to dry and floral blankets for sunbathing. I knew they disapproved of women like me – women who had jobs, ‘office’ women who were unfamiliar to them. But their leaders had instructed them not to speak to us. They had been promised that all women would soon stop working outside the home, under their interpretation of religious law. They watched me go past, and I wondered if they wished they could do away with me entirely.

I reached the shuttle bus that would take me to my office, where I worked as a scriptwriter on a radio drama produced by a local NGO. The storyline I was developing involved a young woman called Zahra. She had four children, and her husband was a traumatised war veteran who had lost part of his leg. Since he couldn’t work, Zahra had found a job as a nurse to support the family with help from a neighbour. Her eldest daughter, just 10 years old, took care of her younger siblings and her father while Zahra worked. Zahra was much happier since she started working, and her children could go to school now that she could afford supplies. But then the neighbours and relatives started gossiping about her and questioning her character. Soon the husband grew increasingly annoyed, rude and suspicious too. Zahra felt trapped: if she quit working, her family would be destitute, but if she continued, the sense of others’ judgment might overwhelm her.

Immersed in writing, my back grew tired from sitting at my desk. I raised my hands to stretch and put them on my head. My colleagues, three other women, were busy. When the Taliban came, our offices were segregated by gender. We’d previously been in an open-plan office, where men and women mixed freely and could share storylines and ideas. The ease of interaction made it easy to collaborate, and it was a friendly and respectful environment, with the intimacy of a family. What would the regime take away from us next?

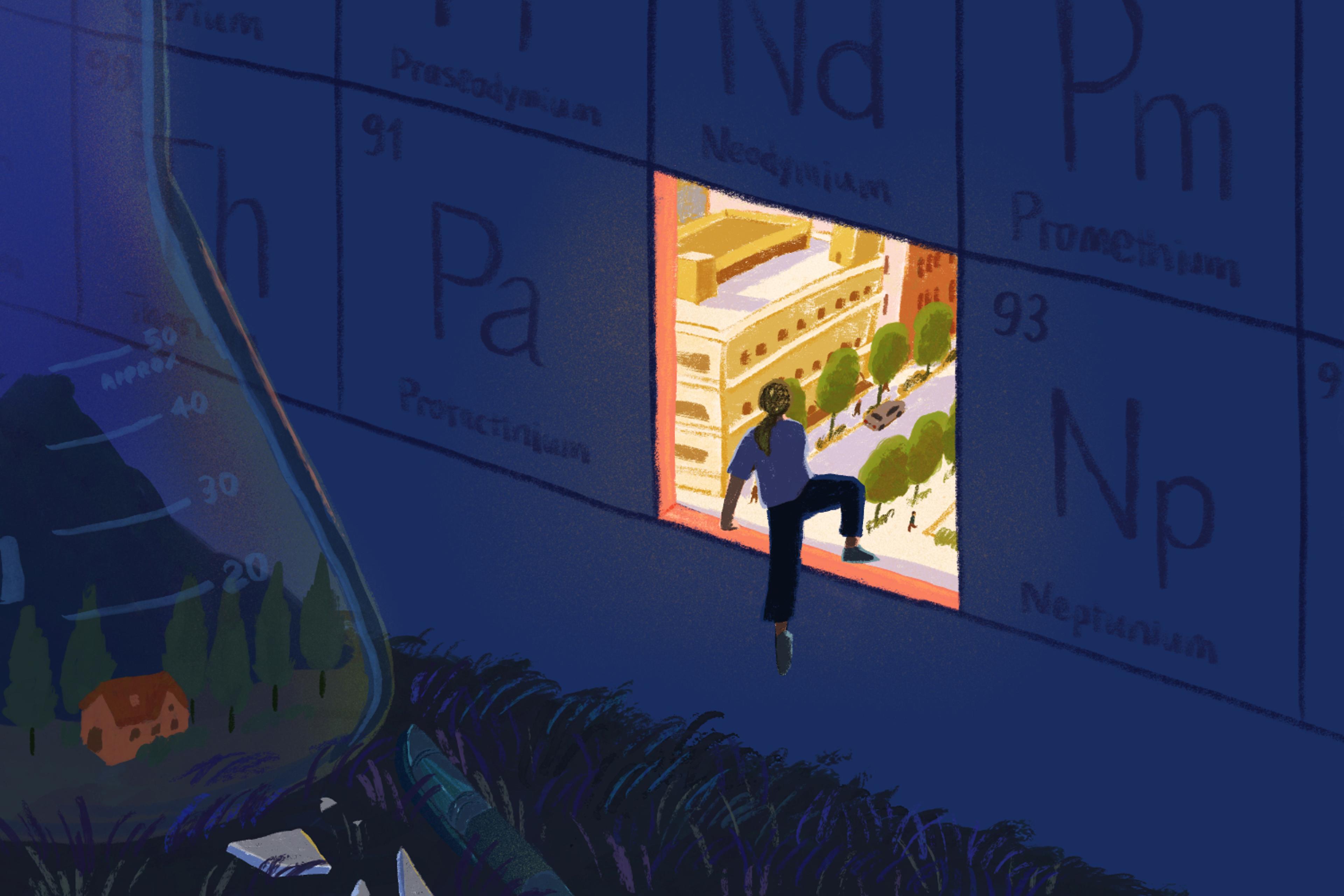

Two years ago, on 15 August 2021, the Taliban took over. It was the last day of high school for my daughters, Nooria and Madina, who were 18 and 16 at the time. Since then, they had been barred from further education, including taking the university entrance exams. The Taliban declared them graduates, yet denied them their certificates. They took away our fundamental freedoms – the right to work, to education, to dress and walk freely in public spaces, to travel overseas alone. They never gave anything back.

Nooria and Madina were now enrolled in a private school in Kabul to get their English language certificates, even if their high-school certificates were beyond reach. My husband and I had always emphasised education and encouraged them to study hard, and they had applied themselves diligently. We’d recently learned that they’d received scholarships to study at the American University of Afghanistan, which had relocated from Kabul to Qatar.

The online classes had started six weeks ago. But my daughters needed electronic devices, especially as they would be starting university soon. I’d been saving for more than two years to help meet the costs of their education. Nooria wanted a laptop, which cost more than $1,400 in Kabul. My younger daughter wanted the latest iPhone, around $1,850.

I counted the money, added my salary, and returned what I didn’t need to the secret spot

My phone pinged to notify me that my salary had been deposited. Payments were often delayed, so this came as a relief. It was why I’d kept my phone on today.

I turned it off along with my computer, and called the men’s office next door to tell my manager that I had a family commitment and needed to leave early. He agreed. I picked up my salary from the bank and called my daughters to get ready for a shopping trip to the Shahr-e-Naw district. I resisted telling them why, but sensed their excitement.

Nooria and Madina were ready and waiting in the corridor of our apartment, dressed in black hijabs. Both were laughing, looking at each other and at me in anticipation. First, though, I went to my room, locked the door and took out a set of pliers from the drawer in the bedside table. Then I opened my wardrobe and removed the neatly folded clothes from the bottom. I took the pliers and slowly pulled out the nails one by one from the base of the wardrobe, revealing my toiletry bag in the hidden gap below. Inside was a plastic bag, and inside that was another little green toiletry bag where I kept my savings. I counted the money, added my salary, and returned what I didn’t need to the secret spot, replacing the board and nails.

After the girls had arranged their headscarves, we hailed a taxi and got off at the Ansari roundabout. I noticed the excitement in Nooria’s and Madina’s eyes as we started walking towards the Khpalwak electronics shop.

‘Mum, are we going to Khpalwak?’ Nooria asked. I just smiled under my mask, and I knew Nooria could tell from the wrinkles around my eyes.

As soon as we arrived, someone opened the door and welcomed us. The shop was in one of the high rises on the main road. It was huge but pleasingly warm, with a welcoming sofa near the entrance, and sparkling vitrines containing mobiles, laptops, iPads, chargers and all sorts of other electronics.

Two smartly dressed assistants smiled at us from behind the counter. We were the only ones there. I’d been in the shop many times before, to look and ask about prices. But I had never bought anything. I’d always needed to save up more.

After some discussion, we ended up with an iPhone 14 and a MacBook. I could see both girls were very excited. They wanted to leave the shop as soon as possible so they could go home and activate the devices. Their delight thrilled me, and offset my own queasiness at spending such a massive amount of money – something I’d never done before. As we left the shop, I took the heavy bag from Nooria, scared we’d be robbed on the way home.

Seeing the girls’ sheer joy with their new gadgets was worth it

I had one more destination in mind, so we walked carefully by foot, through narrow roads lined with shops and stalls where cars couldn’t pass. Clothes, groceries, jewellery, antiques and appliances jostled for space alongside phone shops, banks and restaurants. The war had changed many things in Afghanistan, including this road. Once the area had been exclusively for wealthy people. Now it was crowded, filled with people besieged by worry and anxiety; many of them were poor, drug addicts or begging. The signs of war were also visible, with bullet holes in the walls and debris left over from suicide bomb attacks. The shops that had been in families for generations had been sold to warlords, who built the high rises that now obscured the sky.

It was already dark when we reached the bakery, where I planned to buy cakes and cookies for our afternoon tea and the week ahead. The bakery was very old, older than Afghanistan’s war, and known for being the best in Kabul. We entered and the sweet smell enveloped us. Nooria and Madina put on disposable gloves and filled cardboard boxes with their favourite sweets. Nooria smiled at me as she picked some pistachio and butter biscuits, and her favourite cookies made with cornflour. Madina got jam cookies and some savoury kulcha-e-shoor, a specialty in Afghanistan and usually served with qaimaq chai, or sweet Afghan tea. A couple of other customers browsed. The bakery still drew people, though business had declined with the rising cost of living and high unemployment. I paid for our selection, and we took a taxi home.

Nooria and Madina’s father opened the door to us. We were all smiles, though he said nothing until the girls revealed their purchases. Don’t ask the price, I said, trying to laugh. He let it go. I felt some anxiety about spending so much, with the constant worry about when the Taliban would ban women from working entirely. But seeing the girls’ sheer joy with their new gadgets was worth it.

My mind descended into chaos. There was a flood of messages from my colleagues

After our family tea, I remembered to switch on my phone. I saw a notification from my office WhatsApp group. My hands trembled as I read:

From tomorrow, all women working in national and international organisations must stay home until further notice.

My mind descended into chaos. There was a flood of other messages coming from my colleagues. They were upset too. No one knew what would happen now. The drama we were writing had plenty of female characters – how would it work with only male actors?

This is real, I told myself. This wasn’t a nightmare.

I called for Nooria. ‘Mother, what’s happened?’ she asked, worried by my expression. ‘Is everything OK?’

I asked her to read the messages to confirm it wasn’t a scam. She took the phone and her face fell. Then the phone beeped with another message. Nooria read out loud:

Until told otherwise, female employees must not come to work. Defying the Taliban could cost the office our licence to work, and jobs for the men too.

Nooria handed back the phone and looked into my eyes.

The next day, I left for work as usual, dressed in my hijab and face mask. I put my handbag on my shoulder, but saw no other women on the street. An ominous quiet filled the city, the sky clouding over. My heart felt as heavy as the gathering storm. I was the lone rebel against the regime denying my right to work, denying my duty as a mother and provider.

I reached the roundabout. There was no shuttle bus. The men eyed me, ready to challenge. I would not give them the chance. I turned away, and walked slowly, deliberately, in the direction of home.

This story has been translated from Pashto by Negeen Kargar, and was developed through the Paranda Network, a global initiative from Untold Narratives and KFW Stiftung to connect and amplify the voices of writers from Afghanistan and those in the diaspora.