‘AITAH for not giving my step-sister my half of her mother’s life insurance,’ reads the headline on a post in the ‘Am I the Asshole’ subreddit – an online community where individuals bring their personal conflicts and problems and ask for judgment. Reddit’s users, largely American males aged 18 to 30, were asked to arbitrate a family conflict. Thirty years earlier, the poster’s father had died and left him the family home in his will, on the condition that his stepmother could remain in it for her lifetime. After his father’s death, the stepmother had thrown out the poster; he wasn’t yet 18. Subsequently they had little contact. When the stepmother died, the poster had finally gained access to his house. Unexpectedly, he also inherited from his stepmother. She had a significant life insurance, which was to be split between him and his stepsister, her daughter. The stepsister thought the situation unfair. She believed she should receive half the house, or failing that, the poster should give her his share of the insurance.

The law was clear. The poster was entitled to both the house and his half of the insurance. But was he morally correct, he asked Reddit? Factors to consider when making this judgment were the lack of emotional relationship between the stepmother and the son – was he entitled to this money? There was her bad behaviour when he was a teenager – maybe the inheritance compensated for this wrong? The length of time his stepmother had lived in the house might also matter – 30 years was a long time and her disinheritance by her husband might have been unfair? Another child who was raised in the house and lived there recently – his stepsister – might also have attachments to the property that should be acknowledged in some way. The poster’s father and stepmother had made decisions about their property, but Reddit was left to consider whether these decisions were correct and what mattered when distributing property within the family.

Reddit’s users uniformly agreed that the poster was ‘Not the Asshole’, but their logic varied. Some thought it was compensation for a wrong; others thought the wrong reduced his entitlement to the cash. Many recommended that he get the property assessed and use the money for any repairs, before returning the balance. Others thought he could donate the money to charity. Reddit’s commentariat then were sympathetic to the dilemma posed, but how they interpreted the flow of inheritance and what should inform its direction was far from uniform.

Why did Reddit’s audience come to such different decisions? Indeed, how do we decide what a fair inheritance might look like, or what feelings might motivate it? Very often, we turn to our own family histories. What was normal for us should be normal for everyone, right? As we age and become more worldly, perhaps as we date and come to know other families, we learn that families do things differently from each other. That this is the case is often a significant area of conflict within marriage.

European families of the 17th and 18th centuries were sensitive to the challenge of different family cultures. Around the age of 12 to 14, children were placed in the households of other families. Working-class children generally were put to work, often in domestic service or as an apprentice. Upper-class children went for extended stays with relatives or family friends. As well as learning a skill or accessing a new circle of acquaintances, learning about other family cultures was viewed as an important part of a youth’s education. For girls especially, the expectation that they would subordinate themselves to a husband in marriage meant it was crucial to learn some flexibility. But even for men, there was value in knowing about different ways of living and managing a household. Neither this education, nor patriarchal norms for married life, entirely resolved marital conflicts about how things should be done, however.

The families we live with, are raised by, play a critical role in shaping our imagination and what we think is possible for ourselves and for our children. When we plan for our futures – the age we desire to marry, the number of children we want, whether a mother will work or stay at home, who we shall let kiss our baby – the experience of our own families guides our expectations. While we might critically engage with that experience, wishing to do things differently, nonetheless our families provide an important norm that guides our action. Indeed, as much of what we do within the family feels natural to us, we don’t always recognise the possibilities for change. Learning about how other families have done things can provide important perspective.

Feminist scholars asked how resources were shared across men, women and children

The History of the Family is a large field of scholarship that explores how other families have done things in different times and places. Early interest in the family came from demographers, who wished to understand why the European population boomed in the second half of the 18th century. The structures of a household, who lived with whom and for how long, were viewed as important to explaining when people married and how many children they could have. Freedom from parental oversight, it was suggested, might provide more opportunities for sex.

Later historians became interested in the dynamics of family life. They asked how strict hierarchies of power within families competed with affection between its members. They wondered how people felt about their children, especially when about half of them would make it out of infancy. Feminist scholars interrogated the competing interests that existed within families, asking how resources were shared across men, women and children, and how conflict was mediated or managed within the household.

As a body of work developed, historians were able to make comparisons across time and place and to chart historical change and continuity. While the historic family had been believed to be large and complex, with many generations sharing a home, demographers learned this was not always true. In Western Europe, the nuclear family – mum, dad and children – had been the norm from the medieval period onwards. Indeed, multigenerational households became more common after industrialisation and as families moved into cities in the 19th century. This was quite different from many other parts of the world, where the multigenerational household was widespread.

Historians also learned that the age of marriage was relatively late for Europeans – in their mid-20s – and that large numbers of people, up to a third, never married. The age of marriage fell dramatically in Europe and the Anglophone world, and the numbers of people marrying reached an all-time high, only after the Second World War. The marriages of our grandparents and great-grandparents were a historical anomaly.

That not everyone lived in a nuclear family raised questions as to the multiple family forms available in past societies. Bachelor and spinster households, where people lived with others of the same sex, were common in many European societies. Some of these families may have been romantic couples, but even where their relationship was not sexual, these households provided examples of alternative forms of family and intimacy to the nuclear norm. An interest in sexuality in the past has flourished and drawn attention to the many ways that people have lived together, formed households and expressed affection.

Histories of family emotion have also been important. The rise of the scientific discipline of psychology in the later 19th century brought with it new ideas about the emotional drivers of family life and how healthy adults and children should express themselves. Early histories of the family sometimes attempted to apply these ideas backwards on past societies. They sought to explain the behaviours of historic people using psychological rules. This rarely went well. Historic people did not behave as psychology thought they should. Historians of emotion were interested in why this was the case. Their research suggests that our emotional lives are not just a response to biological drivers, but shaped by social and cultural norms. What we feel and how we respond to a situation are learned behaviours, and so vary across cultures. Whether we view emotion and its related behaviours as moral or sinful, good or bad, also varies across time.

Using these insights, historians of emotion have explored the many different ways that people expressed emotions within their families and how these have evolved. Fashions in emotional life became visible. For example, 18th-century parents were expected to be caring and affectionate, withholding violence and even corporal punishment. Advice books encouraged them to allow children to experience natural consequences for their behaviour and thus learn through doing. In the late 19th century, Sigmund Freud thought that too much affection could spoil a child, and encouraged parents to withhold their affections. Some controversial parental advice books of the period even advocated a stop to kissing children, suggesting that parents should, at most, kiss their child on the forehead before bed. By the 1940s, psychologists were promoting ‘attachment theory’ where children should once more experience abundant love – you couldn’t ‘spoil’ a child with affection, they argued.

Paying attention to the family helps explain a broad range of other historical problems

Trends in emotional life are shaped by wider cultural ideas, variously drawn from religion, from advice writers, from psychology, from popular culture and, of course, from social practice. Some family behaviours have amazing longevity because they are valued and transmitted over generations. The History of the Family charts these evolutions, looking both at the ‘ideals’ found in books or on television, and at how families translated these in practice. Here there can be significant variation even within a particular society. Class background, ethnic heritage, education and many other dimensions influence how families behave.

The History of the Family provides important insight into why past people behaved as they did – and so into the course of history itself. The family has been the central unit of society for most of history. It is here in the ‘nursery of the nation’ that citizens are made, and it is our commitments to its members that have directed many human activities. Decisions to start a ‘family business’, to disperse an inheritance to children, to migrate, have been shaped by a desire to support or improve our families. Paying attention to the family and our affections helps explain a broad range of other historical problems and so requires integration into any model of historical change.

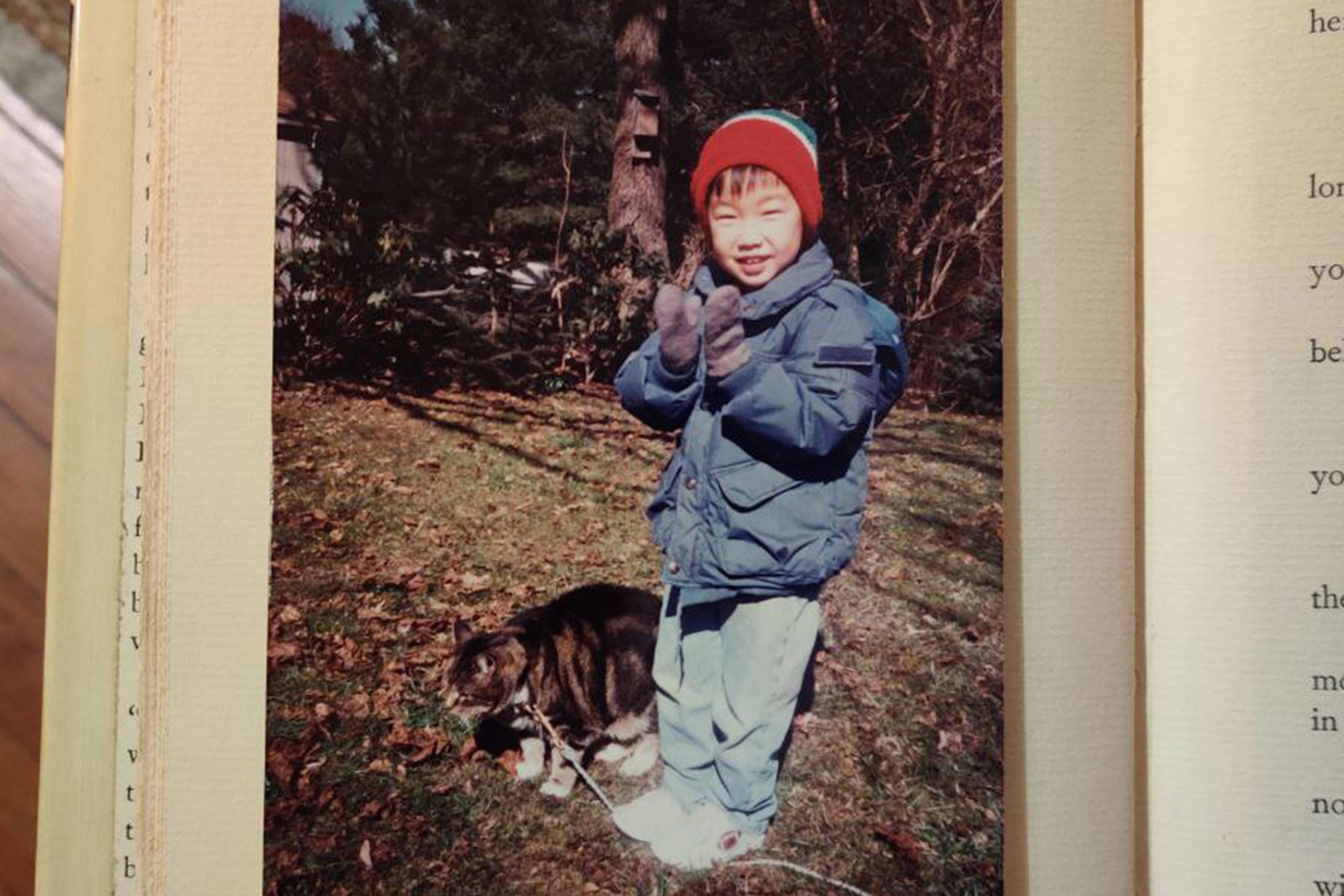

As well as helping us better understand the past, a key value of the History of the Family is opening up the complexity of our ancestors’ affections for today’s families. Leaving a ‘life interest’ in your house to your wife, but willing the final property to a son, was a fairly standard inheritance practice for early modern Britons. Similarly, providing cash for a daughter, but refusing her rights in land, was routine. Such decisions reflected that land was expensive, scarce and associated with the creation of lineage – letting property descend through a named heir allowed the family to continue. Other children – the ‘spares’ – were compensated but not in the same way. Emotion could matter here. A strange decision in a will might be justified by the affection that the deceased had for the beneficiary. But that an absence of love might create a moral obligation to walk away from an inheritance would have been a strange claim. The Reddit poster’s dilemma was one from another age. Except that in another age, few would have thought that a woman had an equal right to a house as her brother. And the value that families placed on affection in inheritance processes would have led to different conclusions.

Past families made different decisions, because what they valued, how they felt about each other, and what they thought was ethical varied from the present. Far from a universal institution, the family and its feelings are historically contingent and changing. This is a liberating idea. Knowing that your family practices are not set in stone, but capable of transformation, provides new opportunities and possibilities. Individuals whose emotional lives or relationships go unrecognised by contemporary society are invigorated by having new (or rather old) models to emulate or explore. Learning about other people, their attachments and how they negotiated complex problems together also provides real insight into an unstable human nature. The historian of the family tasked with adjudicating a conflict on Reddit will bring a depth of wisdom, not just from today, but from across time and space.