Cantankerous, sexually perverse, too-smart-for-her-historical-situation, possibly corrupt: this is what I look for in a female narrator or protagonist. I’ve had enough of hope, and achievement, and of women being excellent. I’m tired of fixating on positives. More interesting to me are characters that reflect how dreadful, compromised and utterly burnt-out we are. According to the book-reading spreadsheet I maintain, so far I’m having a pretty good year for misanthropic lady novelists.

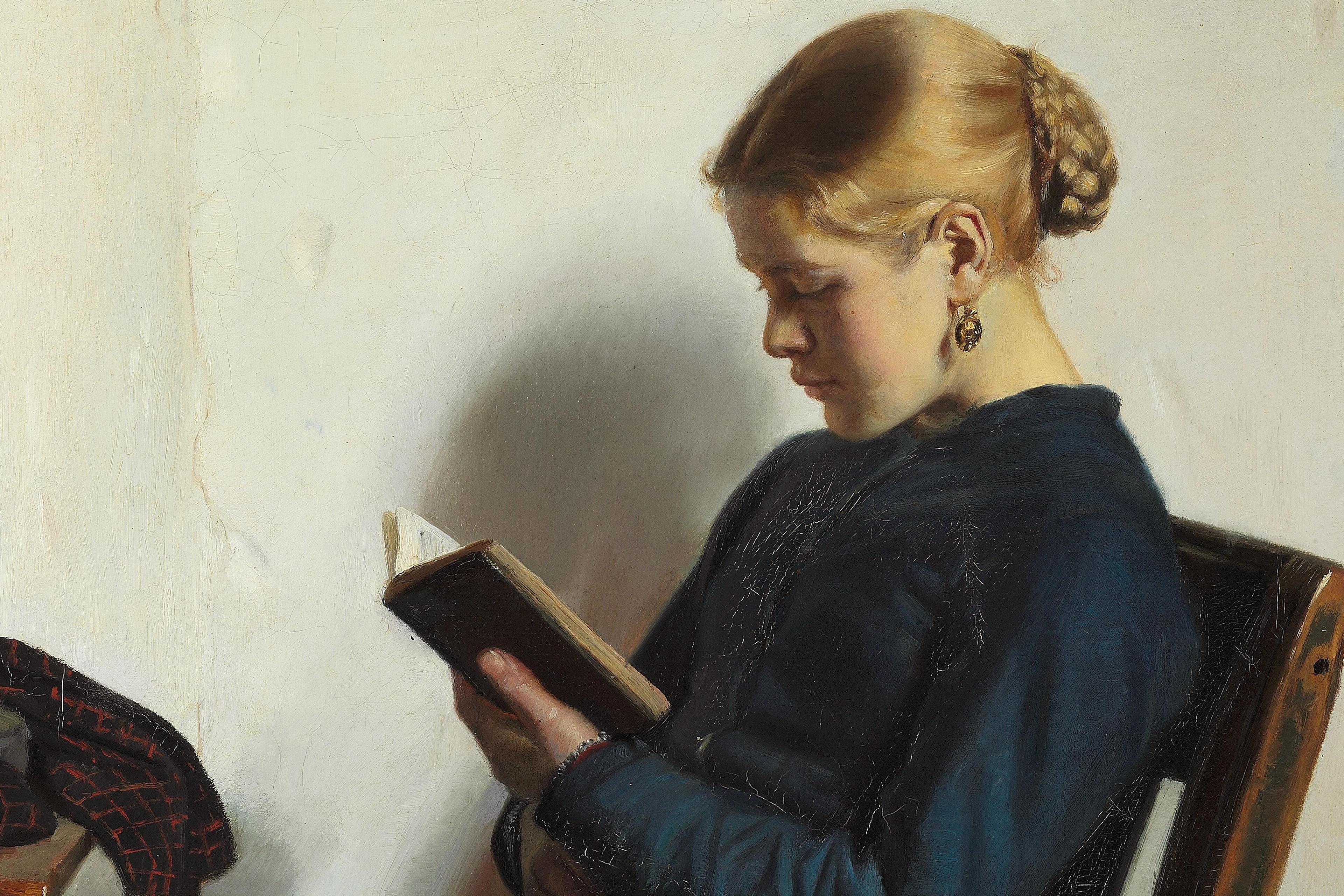

At the beginning of Vigdis Hjorth’s novel A House in Norway (2014), we meet Alma, a middle-aged tapestry artist who lives in a house she bought cheaply after an amicable divorce. Alma does up the granny flat and rents it out to transient people such as ‘The Pole’ (Alma can’t be bothered learning the woman’s first name – too Polish, too difficult), and the Pole’s young daughter. The rent provides a small line of income to supplement her irregular artist fees. ‘She didn’t want to have anything to do with her tenants,’ writes Hjorth, ‘she didn’t want to see them; she just wanted the money going into her bank account every month and then to forget that they were there.’

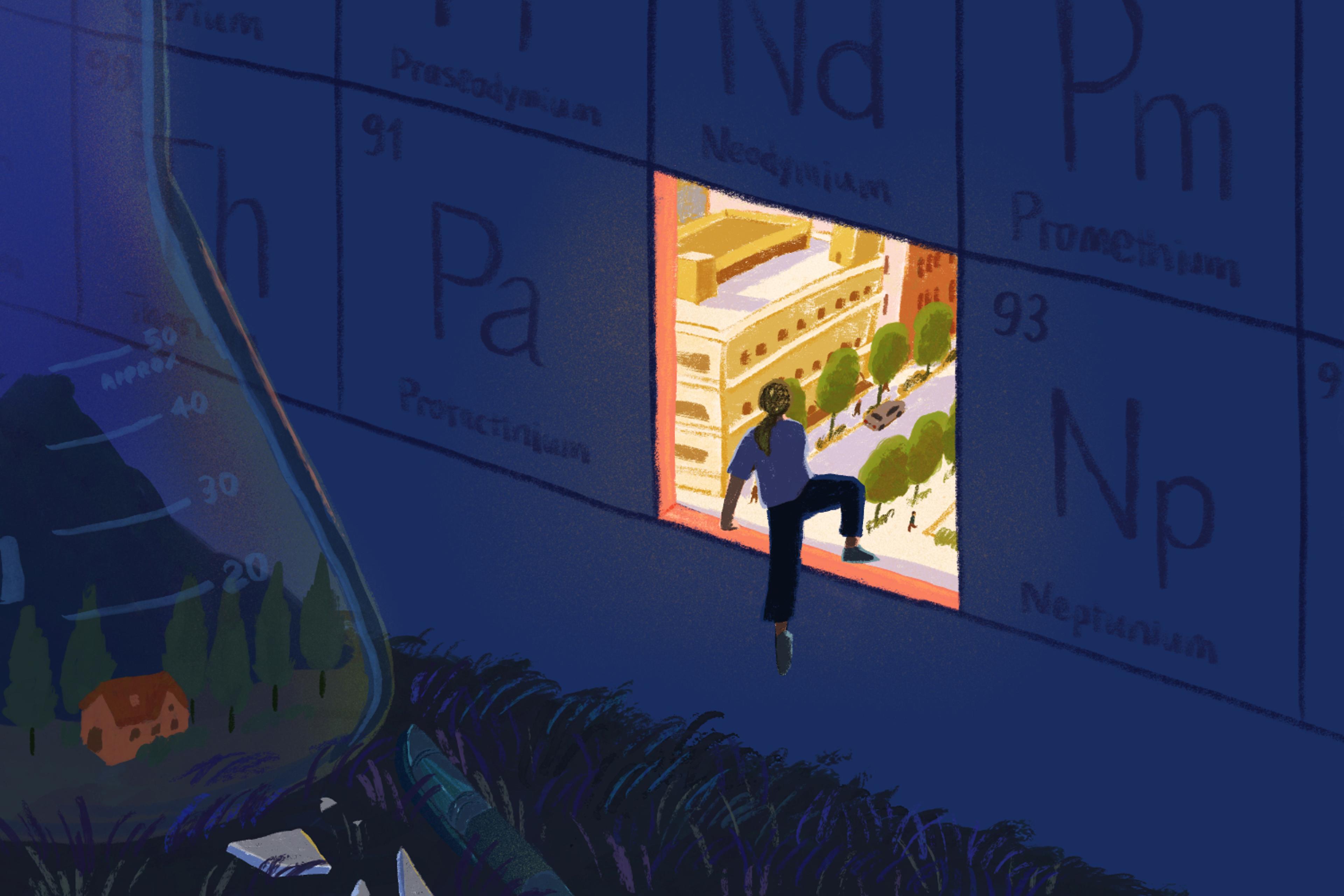

Alma’s enormous tapestries hang in public buildings, as monumental as they are invisible. One of them, she thinks, might be doing its magic unseen, the way architecture does its work: ‘the way our surroundings have been proved to affect us, though we’re unaware of them’.

The protagonist in Hjorth’s novel is a dysfunctional woman, but not tragic. She works all night on her tapestries, and necks bottles of wine in the early hours of the morning to get herself to sleep. When her adult children arrive for holidays with their kids, Alma understands what her duties towards them are, but she also understands, acutely, that she wants them gone.

Alma is a careless, selfish landlord, and a hypocrite. But A House in Norway is not a morality play. Yes, Alma struggles against the collective oppression of women; she thinks deeply, and structurally, about her society. But she also happens to be unwilling to apply her critical insights to herself.

For some reason, this is incredibly vitalising. Here is a woman whose deep flaws don’t result from trauma, or her mother, or her children; she is not reacting against poverty, male betrayal or erasure, or unfulfilled artistic potential. She is at once structured by, and an agent of, social violence. The pleasures of Alma’s maladaptations are not that she is heroic, or courageous, or even particularly rebellious. (Hjorth writes that ‘Alma had never, she realised that now … met any angry women, women who rebelled. Frustrated and mentally crippled yes, but not rebellious.’) The pleasures of this character boil down to the fact that her flaws are the ordinary derangements of many people who live in unjust, casually brutal societies.

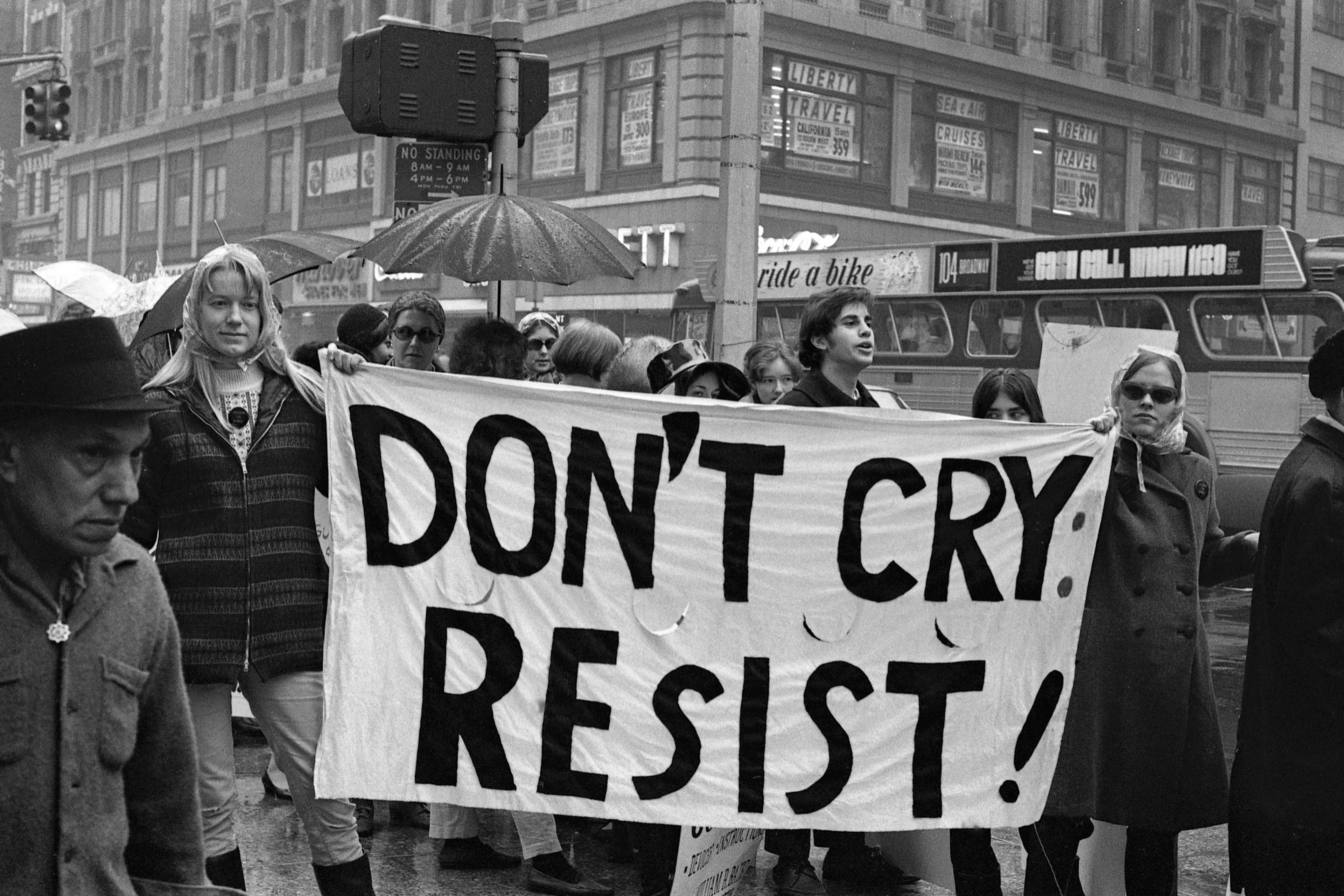

Characters such as Alma have populated my reading this year, spanning the works of Sigrid Nunez, Doris Lessing, Lynne Tillman, Danzy Senna and Jamaica Kincaid (of whom I’m now a completist). They strike me in some way as unlikely feminist woman characters: sometimes mildly sociopathic, or brazenly complicit, or resisting survivor narratives. Not role models. Not goody-two-shoes. Not ‘having it all’ (they kind of reject it all). But the characters are active. The women resemble both the hopes and the failures of previous generations’ political struggles, and they do so in ways that make me hopeful about the future, in which women might be untethered, finally, from the expectation of being perfect. Like Villanelle from the eponymous novel series and TV show Killing Eve (2018-); like Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag; like Ursula, self-appointed queen of the sea, from the Disney movie The Little Mermaid (1989).

Something I’ve been uncomfortable with for many years is how uncomfortable fourth-wave internet feminism makes me. Why should I feel this way? I, too, am angry about How Men Are and The Harm Men Cause a great deal of the time. Yet every time a novel comes out with the word ‘Girl’ or ‘Woman’ in its title; every time a new internet essay comes out declaring that women are this or that, that we have been trained to be small and polite, that our lives are centred around self-sacrifice, that we are wonderful rule-followers, to our detriment – something within me withers. I think, instead, of the women who don’t accept those ideas, who fester in their rage and disappointment, and who – inevitably – let it deform them.

Why should I object to women claiming feminism in order to free their minds and hearts? Why can’t I simply welcome the proliferation of women’s orgs and festivals and groups and magazines and parties?

It’s something to do, I think, with how the contemporary politics of identity flattens and homogenises – and encourages potentially dishonest, aggrandising, and exploitative self-representation. When women decide to join forces against male domination, we are encouraged to believe that our oppression marks us in predictable and repeatable ways. Say, because of certain historical social formations, women are more self-sacrificing than men. Or, we are destined to choose our families over our artwork, leading to the inevitable grief of unlived potential. Or, due to our historically imposed roles as domestic labourers maintaining collective social units, we are conditioned for intersubjective sociality, and are therefore better at sharing power and resources.

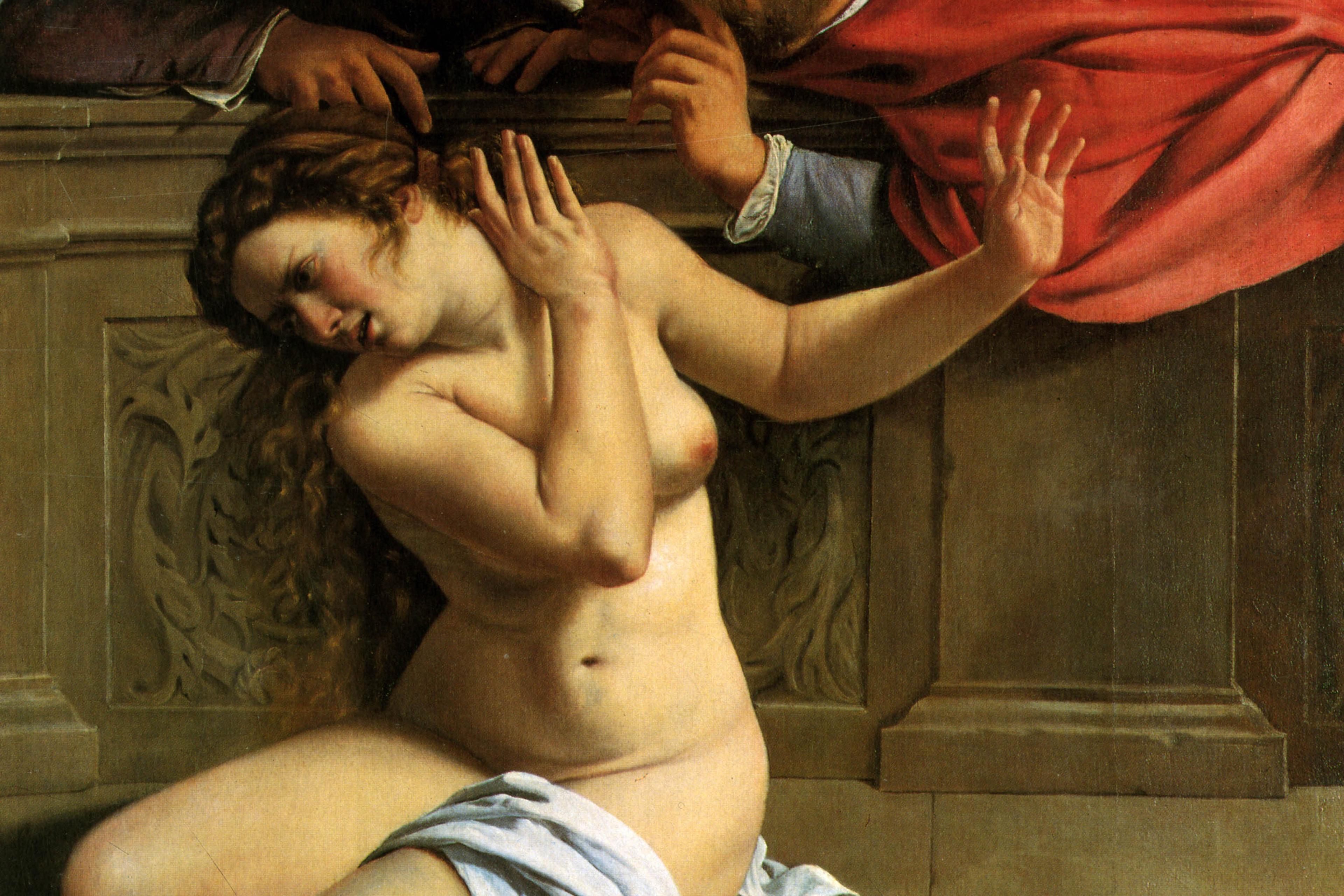

The problem is that, as a political framework, this narrative leaves out the reality of women’s capacity for violence, greed, self-delusion and irresponsibility. Women’s ability to be active agents in their own lives, even when their activities might be destructive. What happens when women are supposed to be civil, and a woman behaves uncivilly? How do we account for that?

These characters I find thrilling are women who are absolutely not socialised or charitable or good at doing anything much, other than drinking straight from the bottle and ruining other people’s lives (and their own). The argumentative, the hostile, the poor and pissed-off. Ambivalent daughters, ambivalent mothers, ambivalent communists, ambivalent apaths. Women who refuse to bury the hatchet or reject outright the fact of their oppression. Their oppression, in other words, doesn’t necessarily produce qualities of kindliness, resilience or extraordinary high achievement. It produces resentment, emotional dysfunction, ambivalence and the possibility of covert violence. Women are often disfigured – and not in charming ways – by what society has done to them, and they go on to be complicit in the disfigurement of others.

Take Anna Wulf from Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook (1962). Anna represents the narrative centre of that fragmenting and fragmented epic of a novel. She is an intellectual and an active, engaged, citizen. But being so mindful of her place in history and in politics, she unravels under the burden of her personhood. She is not only a communist, but a woman; not only an author, but a woman author; not only a lover, but a mother. She struggles against the compromises she must make as a woman who writes, and a woman who loves men and is also trying to raise one. Anna is an ambivalent radical-artist-mother-lover, a woman whose feelings have had no place in her political formation, and who charges towards her own burnout and disfigurement. She breaks with the Communist Party of Great Britain around the time of the Soviet Union’s 20th Congress of 1956:

Why can’t we say something like this – we are people, because of the accident of how we were situated in history, who were so powerfully part – but only in our imaginations, and that’s the point – with the great dream, that now we have to admit that the great dream has faded and the truth is something else – that we’ll never be any use.

I don’t want all the women in the world to be dysfunctional in the ways that Alma is dysfunctional, or as odd, or bad as her. I don’t want to burn out the way Anna does in her struggle against the weight of history. I just really like novels about these women, because they make me feel slightly better about being a grump and a pessimist. Women are women, not because they necessarily share any particular qualities, but because they share a collective history. These characters remind me that I don’t have to lose weight or model perfect progressive values or charm every waiter I meet in order to be a person actively engaged in the project of my life, or to be a person shaping herself and the world around her.