The English suffragette Millicent Fawcett was bemused by ‘women who petitioned against women’. In her book Women’s Suffrage (1912), she bemoaned ‘the inherent absurdity of the whole position of anti-suffrage women’. How can anyone explicitly and consciously favour a patriarchal system that repeatedly and routinely harms them? As the US feminist Andrea Dworkin wondered more than 70 years later in Right-Wing Women (1983), how can women believe in the justice of a system ‘in the face of proved atrocities and the obvious intractability of the oppression’ that they suffer every day?

Fawcett and Dworkin were on to something: some of the most vocal resistance to votes for women in the early 20th century, against the expansion of women’s rights in later decades, and against the continued struggle to combat gender oppression today, comes from women. How can this be? Perhaps some white, middle-class women – the predominant demographic of the anti-suffrage campaign – are driven by self-interest, looking to preserve their life of relative privilege. For the conservative US activist Phyllis Schlafly, who in the 1970s successfully mobilised masses of women against the US Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), anti-feminist work might have been a way to gain political recognition. Alternatively, perhaps some women are alienated by feminists and their popular image. ‘Right-wing women fear lesbians,’ Dworkin wrote, of the hostility she encountered at the National Women’s Conference in Houston in 1977: ‘to them, the lesbian was inherently monstrous, experienced almost as a demonic sexual force hovering closer and closer.’ Or maybe some women have simply been fortunate or sheltered enough not to experience extreme gender oppression. Anti-suffragettes, Fawcett wrote, ‘“lived in a balloon”, unconscious of what was happening among the dim common populations living on the Earth.’

Yet even women who are privileged or protected will likely experience or witness oppression when they, their daughters and their female friends are sexualised, put down, talked over, violated, abused, ridiculed or simply ignored. Shouldn’t these experiences arm them with knowledge about oppression? Shouldn’t it make them feminists, rather than anti-feminists?

Unlike Fawcett, I don’t believe anti-feminist women are inherently absurd. They frequently don’t experience the oppression they do face as oppression, but perhaps as a compliment or oversight – and there’s a perfectly good explanation for that. It’s easy to fixate on the idea that, deep down, the oppressed must know that they’re oppressed, but they must have some sort of gut refusal to accept it, despite some tacit, unconscious knowledge, some scant, half-baked understanding. Somewhere within anti-feminist women there are ‘internal conflicts’, says Dworkin; paying attention to those conflicts will unearth the oppressive ‘realities of their own experiences’.

A detour into the world of art helps us see why this explanation is naive. Just like an artist can completely influence a spectator’s experience of a painting, so social contexts can determine experiences of oppression all the way down.

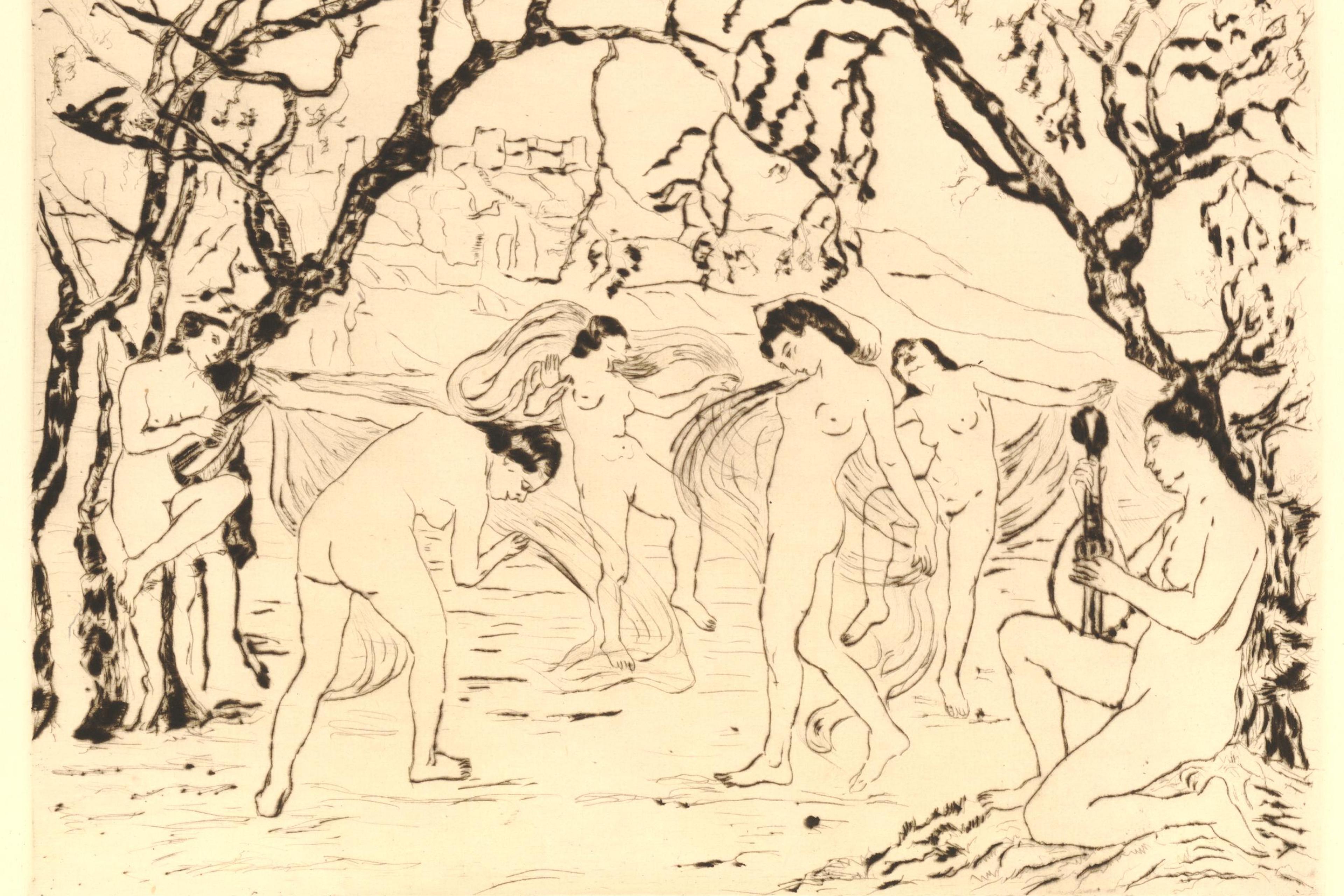

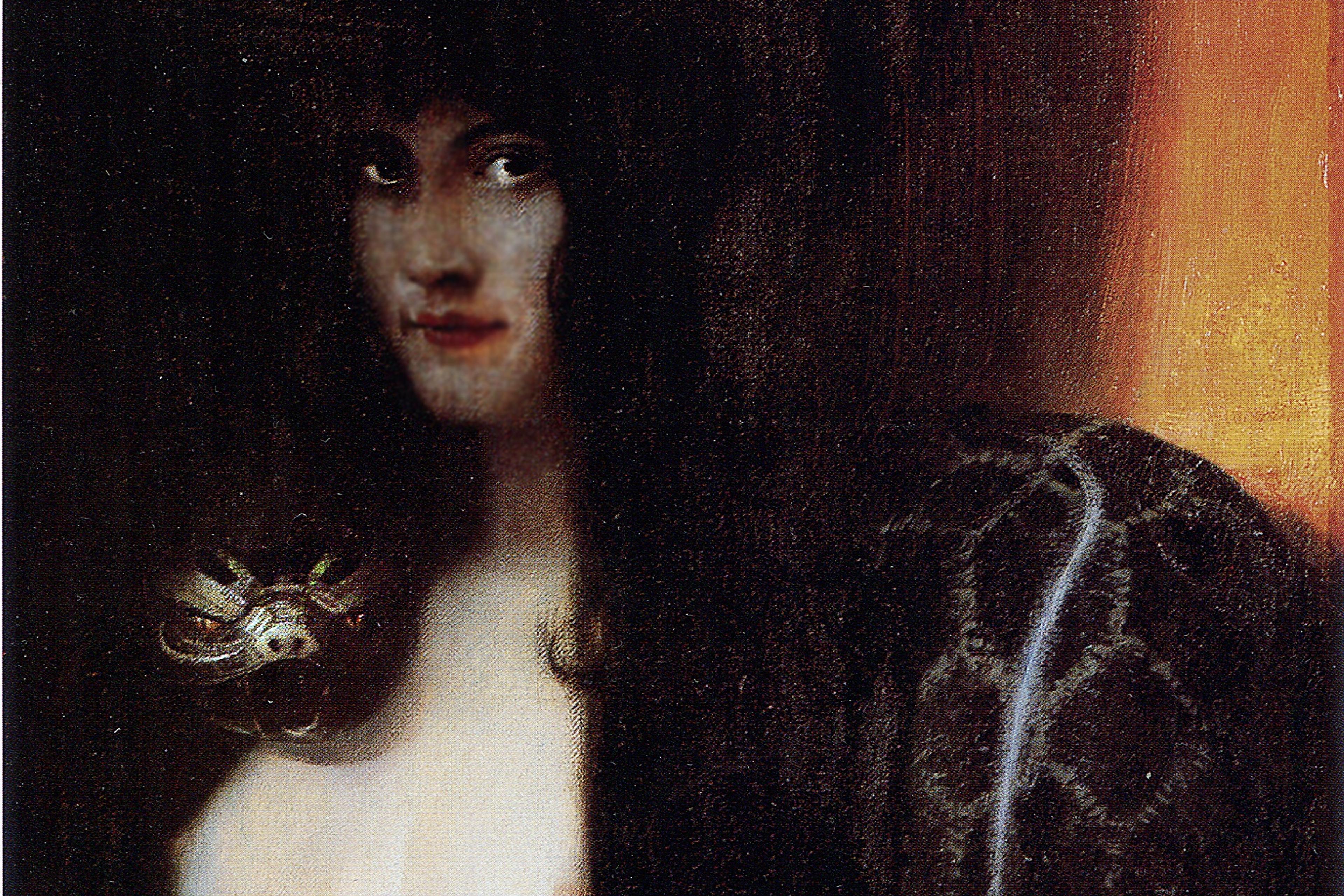

The biblical story of Susanna and the Elders is a popular motif of Renaissance paintings. Susanna, taking a quiet outdoor bath, is interrupted by two male onlookers, scheming to rape her. As Susanna cries out for help, the two men threaten to tell the authorities that she – not them – behaved inappropriately: a classic ‘he-said, she-said’ situation. Tintoretto’s rendition of this story shows Susanna undisturbed, gazing at her naked body in a mirror. Her bright skin against a darker background immediately attracts the spectator’s eye. He (as this semi-pornographic painting is clearly aimed at a male audience) will likely first overlook the two spying Elders. Tintoretto’s depiction invites the male gaze, secretly observing a beautiful woman. The viewer is complicit in the Elder’s crime – or is it really a crime?

Susanna and the Elders (1555-56) by Jacopo Robusti, called Tintoretto. Courtesy the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna/Wikipedia

Carracci shows the Elders as they start harassing Susanna. She displays some resistance, holding on to her robe as one Elder tries to pull it away from her. Yet, she looks at him from below, not shocked, but almost seductively. Perhaps this is the Renaissance version of ‘her no is really a yes’?

Susannah and the Elders (1616) by Ludovico Carracci. Courtesy the National Gallery, London

Artemisia Gentileschi depicts a naked Susanna in the foreground who has just noticed the observers behind her. The Elders are clearly visible. Susanna isn’t primarily beautiful; she’s vulnerable. Her head is turned away, unwilling to face the violence she knows will come. She lifts her arms in a gesture more of disgust and resignation than of defence.

These paintings depict the same story of Susanna and the Elders. Yet each invites its own interpretation of Susanna, who also seems to stand for women generally. First, she is a mere beautiful object; next, she can’t decide between resistance and seduction; last, she understands her powerlessness and expects violence. There’s no need for accuracy hidden in the pictures (especially not in Tintoretto’s and Carracci’s) about what really happened to Susanna, about how women actually are, or about the crime that rape truly is. A spectator’s interpretation of the story, guided by one of these pictures, need not contain any truth, no matter how half-baked, scant or unconscious.

Perhaps our encounters with oppressive real-world events can differ from one another just as much as these paintings. Just as artists invite different interpretations of women, so the real world invites different interpretations of real events.

Like Susanna, real women are characterised in divergent ways. A housewife is seen to enjoy the ‘special privileges’ of her role, as Schlafly writes in 1972. Or she is deemed to do the only work her ‘physical constitution’ equips her for, as one anti-suffrage pamphlet put it in 1889. Or she is understood as ‘being systematically exploited and abused’, both economically and sexually, as Dworkin believed. Abortion can be perceived to involve taking a life, or to be preserving existing (women’s) lives. These characterisations shape one’s experiences of being a home-maker, meeting a stay-at-home mother, or hearing about an abortion. Experiencing one’s homemaking life as a privilege need not involve any internal conflict based on the sense that homemaking is exploitative.

But why do some of us have distorted characterisations while others tend to employ more accurate ones for the same situations? I think that patriarchy works a bit like a good artwork: it invites us to have particular characterisations. What characterisation is cued depends on the social context.

An artist cues an interpretation using artistic devices such as light, composition or colour – we saw how Tintoretto, Carracci and Gentileschi do so above. In the real world, others tell us their interpretations of events, some interpretations become established as truisms in certain contexts, and so we are prompted to adopt them. Cuing can also be more subtle, more closely resembling the elegant, non-obvious cuing of artistic devices: using specific terms over others to describe parts of the world suffices to cue anti-feminist interpretations. Pregnancy might be described as involving ‘unborn children’, or ‘infants’. These terms license inferences, a point I borrow from the US philosopher Lynne Tirrell: unborn children are children; children and infants are clearly human beings; killing human beings in clearly wrong; so abortion is clearly wrong. Referring to the family home as a ‘nest’ (as Schlafly did in her Stop-ERA newsletter) licenses the inference that the home is cozy, safe, nurturing and comfortable – that it needs protection and preservation. Describing some women’s lifestyle as ‘homemaking’ licenses the inference that it is a valued, active task with autonomy and responsibility.

Such inferences don’t need to be conscious, and cuing can bypass explicit opinions or beliefs, directly influencing one’s intuitive experiences of the world. Terms such as ‘nest’ can imprint a perception of homes as cozy and protective. These terms can shape behaviour around one’s home, one’s emotional relation to one’s home, one’s assessment of other homes and, importantly, one’s interpretation of oppressive events in the home, such as the gendered division of labour or experiences of sexual abuse. The message is that sexual abuse that takes place in a safe, nurturing environment cannot be abuse. It must be an accident, a misunderstanding, or some other innocent thing. In this way, oppression is experienced as something else entirely, and so anti-feminist beliefs about the non-existence of oppression arise.

My hunch is that many anti-feminist women live in environments where characterisations about the safety and privilege of the home, the virtues of motherhood, or the status of unborn children are frequently socially cued. Women in these situations are therefore likely to adopt these characterisations, which in turn enable them to encounter oppression without seeing it as such.

They’re also likely to make these distorted experiences a fundamental part of their identity. Anti-feminist mothers might define themselves over their close relation to their (unborn) children; housewives might see protecting the nest as the job that gives their life meaning. Dworkin gives a similar example for abortion: ‘Forcing women to bear unwanted babies is crucial to the social programme of [anti-feminist] women who have been forced to bear unwanted babies and who cannot bear the grief and bitterness of such a recognition.’ A woman’s self-worth, springing from her role as a mother, would be destroyed if she admitted to herself that she was forced into that role. In this way, anti-feminist worldviews become entrenched.

In the paintings of Susanna and the Elders, characterisations were merely cued – but in real life they’re also enforced. Women who experience the world differently, who dare to voice their diverging views, are deemed insane; they’re hated or despised, or simply ignored and disbelieved. No wonder, then, that some women are sticking to anti-feminist characterisations of the world. Enforcement is not only negative – it can also take the form of reward and praise. Such appreciation fuels anti-feminist perceptions of society, from which convictions and political activism arise. Anti-feminist women are the product of a powerful patriarchal world, shaping and enforcing their very experiences of it. They are not simply stubborn, self-interested, privileged, or merely in possession of different opinions. To get anti-feminists to reconsider their political stance, they need to first have different intuitive experiences – perhaps even a fundamental alteration of one’s identity.