One Friday this February, I took the Métro to the Tuileries Garden, then walked across the old Solférino bridge to the Musée d’Orsay. After scanning my vaccine health pass and joining the other masked visitors inside, I went for a third spin through a temporary exhibition of works from the collection of the painter Paul Signac. It was the show’s final weekend, and I wanted to get one last look at a small painting by Signac’s contemporary and fellow pointillist, Georges Seurat, an oil study of a model standing nude in an atmosphere of blue and lilac brush marks.

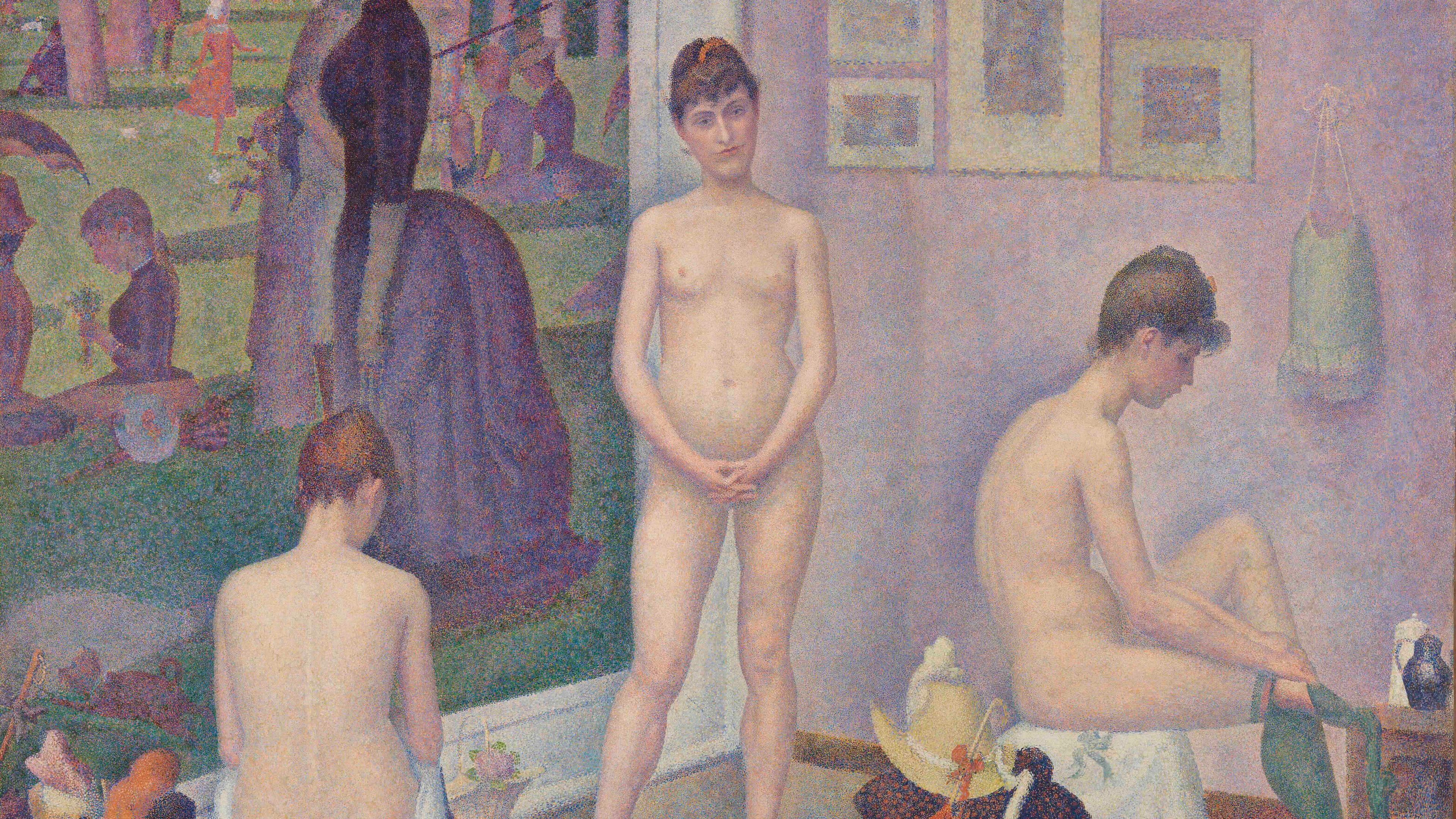

Poseuse debout, de face (1886) by Georges Seurat. Photo courtesy the author

I was immediately drawn to this study the first time I saw it, though it’s no bigger than a piece of writing paper, and was in danger of being eclipsed by the largest Seurat on display, an unfinished painting of an acrobat performing on horseback in the ring, called The Circus (1891). The study – Poseuse debout, de face (1886) – demanded my attention. The particulate blue light floats in front of the model’s body, colouring her skin, but also catching her up in a swirl of atmosphere, a little cyclone of vibrating beingness. Although the model stands in a studio, the colourful aura reminded me of the air on a beach at dusk, when you can almost see the negative ions shimmer, all forms revealed as a swarm of atoms, electric. The atmosphere advances to debunk the myth of material solidity. Signac acquired the study shortly before Seurat’s death, liking sketches as much as he did finished paintings, and noting in 1895: ‘What charm emanates from these smiles and thoughts of a painter.’

All painting is a form of optical illusion, but pointillism – the technique Seurat pioneered in the 1880s when he was in his 20s – aims to deconstruct the act of seeing itself. Trained at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Seurat studied classical art, but he was keenly interested in how the eye interprets colour, and drawn to the theories of the chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul. Chevreul explored the workings of colour after he became director of the historic Gobelins tapestry factory in 1824 – originally a manufacturer of medieval dyes. He observed that two colours, when placed near to one another, would look like a third colour when viewed from a distance, and called the effect ‘simultaneous contrast’.

Chevreul advised painters to incorporate such colour contrasts into their work, referring to its affect as ‘harmony’; Seurat, who copied out paragraphs from Chevreul’s works in his own notebook, was interested in the way it evoked emotion. This visual manifestation of emotion as Seurat experienced it, as a sense of blurred vibration, is part of what makes his works so captivating

With the advent of chemical photography in the mid-19th century, painting began to change. As David Hockney notes in Secret Knowledge (2001), for centuries painters preferred an ‘optical look’, mimicking the life-like projections of light and form made by reflecting devices such as mirrors and camera obscuras. But after photography went mainstream, painting was no longer needed as a documentation tool in quite the same way, and so pioneering painters began to occupy themselves with what black-and-white photography couldn’t yet capture, emulating the ephemeral and the fleeting. Impressionists such as Claude Monet turned their eye to mists, and dusk, and the dappled colours of light on water. Berthe Morisot studied the movement of air across a woman’s bare shoulders in the glow of a low-lit dressing room. If a photograph was a moment frozen in time, a painting still flowed, still breathed: it could defy the pinned stagnation of time. The impressionists liberated colour and form from their former margins, making them the very subjects of the works themselves. Seurat followed on, with further attempts to get at the truth (or the illusion) of what it really is to see.

I wasn’t the only person struck by the small Seurat study. In the museum’s gift shop, I discovered that it was one of the select images turned into a postcard. Simultaneously, I experienced the sensation of reassuring disappointment that my creative sensibilities were not unique, and the dubious pleasure of having my tastes confirmed. This loosely rendered nude, never intended for public exhibition, was speaking to people other than myself. Dispersed throughout the world as a collectible object, like the seeds of a dandelion set adrift, it was releasing spores.

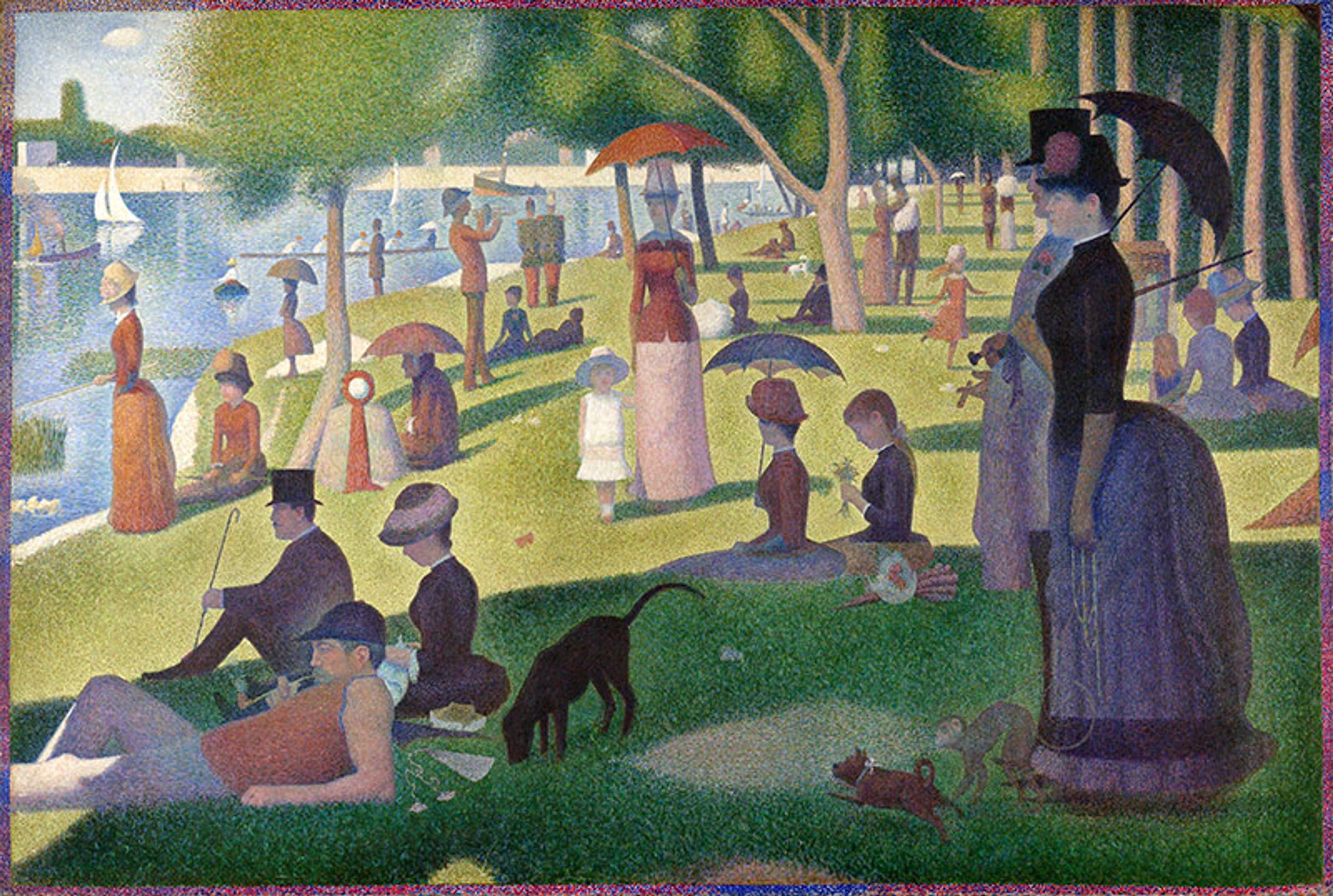

The work is a study for a larger painting called Models (1886-88), now at the Barnes Collection in Philadelphia, that shows three female nudes in a studio. One sits half-dressed on the edge of a settee, her back to the viewer. Another stands, ready to pose. A third, seen in profile, pulls on a pair of green knee-high stockings, beside a pile of clothes and shoes. In the background, on the studio wall, is a partial view of another Seurat painting, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-86), his most famous; three models in front of a painting within a painting. It is one of Seurat’s finest. What was rendered in brushy daubs in the study has been transformed in the final version into a whirring constellation of dots in complementary colours, indigo, peach and acid green.

A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884) by Georges Seurat. Courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago

If you look closely at this painting, the models reveal themselves not to be three models after all, but the same woman shown three times. This raises the question of whether Seurat intended Models as a meditation on the passage of time itself, with all moments happening simultaneously – time collapsing within the meditative space of the studio. On the left, the model arrives, sits on the red settee and disrobes. In the middle, she’s at work; on the right, she readies to depart. That her discarded outfit changes colours from left to right suggests that these moments have been captured on different days. In this way, the canvas invokes the banal reality of painting itself, dependent on practice and repetition, on work put in at the easel, day in and day out. It is a montage, a time-lapse portrait of creative endeavour, that dismantles past, present and future.

Something about Seurat’s work just pulls you in. It possesses a sense of vibrating electricity. The blur of coloured dots promises to reveal something, if only you’d move closer, but then the nearer you get to the canvas, the more the paintings atomise. Sitting on the bench near the Seurat study, I watched it grab people, watched them fall in to it, the way Alan Ruck’s character Cameron does when he encounters A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte in John Hughes’s tender coming-of-age movie Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986). Hughes later described this scene, filmed at the Art Institute of Chicago, as ‘self-indulgent’, since the museum had been a refuge for him when he himself was in high school, and where he came to know ‘all the paintings’.

Of the scene, in which Cameron stares and stares at the mother and child in Seurat’s painting, squinting to get better resolution, Hughes says (in a recorded commentary):

I always thought this painting was sort of like making a movie, you know, the pointillist style, which you’re very, very close to it; you don’t have any idea what you’ve made until you step back from it.

But Cameron does not step back. The closer he looks at the Seurat, the less he sees. He falls into it, experiencing a kind of personal dispersal. The abstracted field of colour composing the child’s face mirrors back to him his own facelessness and lack of belonging, his fear, as Hughes puts it, that ‘there isn’t anything there’.

Life slides away from us, meaning slides away, as does our idea of the concrete self. The mind wants patterns in the same way that the eye wants colours to merge. We are built to do this. We want definition and borders. But sometimes, no matter how hard we try to keep it together, we cannot.

In Elena Ferrante’s novel My Brilliant Friend (2011), Lila confesses the frightening episodes she refers to as ‘dissolving margins’:

[O]n those occasions the outlines of people and things suddenly dissolved, disappeared … It seemed to her that everyone was shouting too loudly and moving too quickly. This sensation was accompanied by nausea, and she had had the impression that something absolutely material, which had been present around her and around everyone and everything forever, but imperceptible, was breaking down the outlines of persons and things and revealing itself.

But the dissolution of our own margins does not have to be frightening. In Richard Linklater’s film Before Sunrise (1995), Julie Delpy’s Céline and Ethan Hawke’s Jesse come across a poster for a Seurat exhibition as they stroll through nighttime Vienna. ‘I love the way the people seem to be dissolving into the background,’ Céline says. ‘Look at this one. It’s like the environments, you know, are stronger than the people. His human figures are always so transitory.’

The couple’s meandering conversation returns again and again to the transitory nature of bodies and feelings in space and time. In the sequel Before Sunset (2004), set nine years later in Paris, an unhappily married Jesse says that if someone were to touch him, he fears he might ‘dissolve into molecules’. In the third film, Before Midnight (2013), they listen as a fellow dinner party guest talks about being able to see her late husband in the mornings:

He appears, and he disappears, like a sunrise or a sunset, or anything so ephemeral. Just like our life. We appear, and we disappear, and we are so important to some, but we are just passing through.

At the end of Before Sunrise, the camera takes us on a tour of all the places that the fleeting couple have themselves passed through: the bridge, the river, the park, the churchyard. As Céline observed, the environment is stronger than the people within it. They have already dissolved into the rest of their lives. But in Before Sunset, there is a similar montage of location shots, but this time it takes place at the beginning. We are shown the settings that await them. They hold the mysterious charge of things yet to come.

Humans are afterimage; we vibrate on the retina of the world after we are gone like the memory of a bright light making shapes against a closed eyelid. But we are also destiny, in landscapes that hold a prophecy of us.

Seurat’s life itself turned out to be fleeting too. He died at just 31, following an unknown illness, and with The Circus still in progress – the grid of blue lines used to arrange its figures still visible on the canvas. The painting had already been hung in its unfinished state at the Salon des Indépendants before Seurat fell ill. For a brief time afterwards, his mother hung it in the room where he’d died. But then Signac added the oil painting to his collection of Seurats, making 14 in total, where it joined the little study of the model swathed in blue.

To me, the Seurat study looks not so much like the model is dissolving into molecules, but that molecules are temporarily forming themselves as her, as though her body were a murmuration of matter rather than a fact. What are bodies, or the experience of them, except the precipitation of feelings in space and time? Maybe we are all like this, murmurations, a flight of starlings, momentarily caught in a form we call ‘self’.