In January 1920, Upton Sinclair wrote to his longtime friend Walter Lippmann about a topic that deeply concerned them both. ‘I have been reading your articles in the “Atlantic”, and it seems that your mind is wrestling with the same problem as mine,’ Sinclair, the muckraking author of the novel The Jungle (1906), told Lippmann, the political philosopher and adviser to the Woodrow Wilson administration. ‘I am just publishing a book dealing with our Journalism, and I have ordered a copy sent to you.’

‘I shall look forward to receiving your book and I shall read it eagerly,’ replied Lippmann. ‘The problem of how to get an adequate press seems to me infinitely the most important problem in modern democracy.’

Lippmann never wrote back to Sinclair about his book, The Brass Check (1919). In fact, the two authors, once frequent correspondents, mostly fell out of touch for the next three decades. Lippmann’s own later book on journalism, Public Opinion (1922), would explicitly deride Sinclair’s argument that the media was beholden to corporate interests. Its publication set off a feud between the two authors that would play out publicly over the next decade. Lippmann prevailed in their debate. His book became a classic for generations of journalists and their critics. It helped push those who sought to reform the profession away from the problems that Sinclair identified – profit and power – to the one that Lippmann diagnosed: psychology.

Upton Sinclair (centre) outside the Standard Oil Building, having previously been arrested for protesting the conditions of Colorado mine workers, c1914. Photo courtesy the Library of Congress

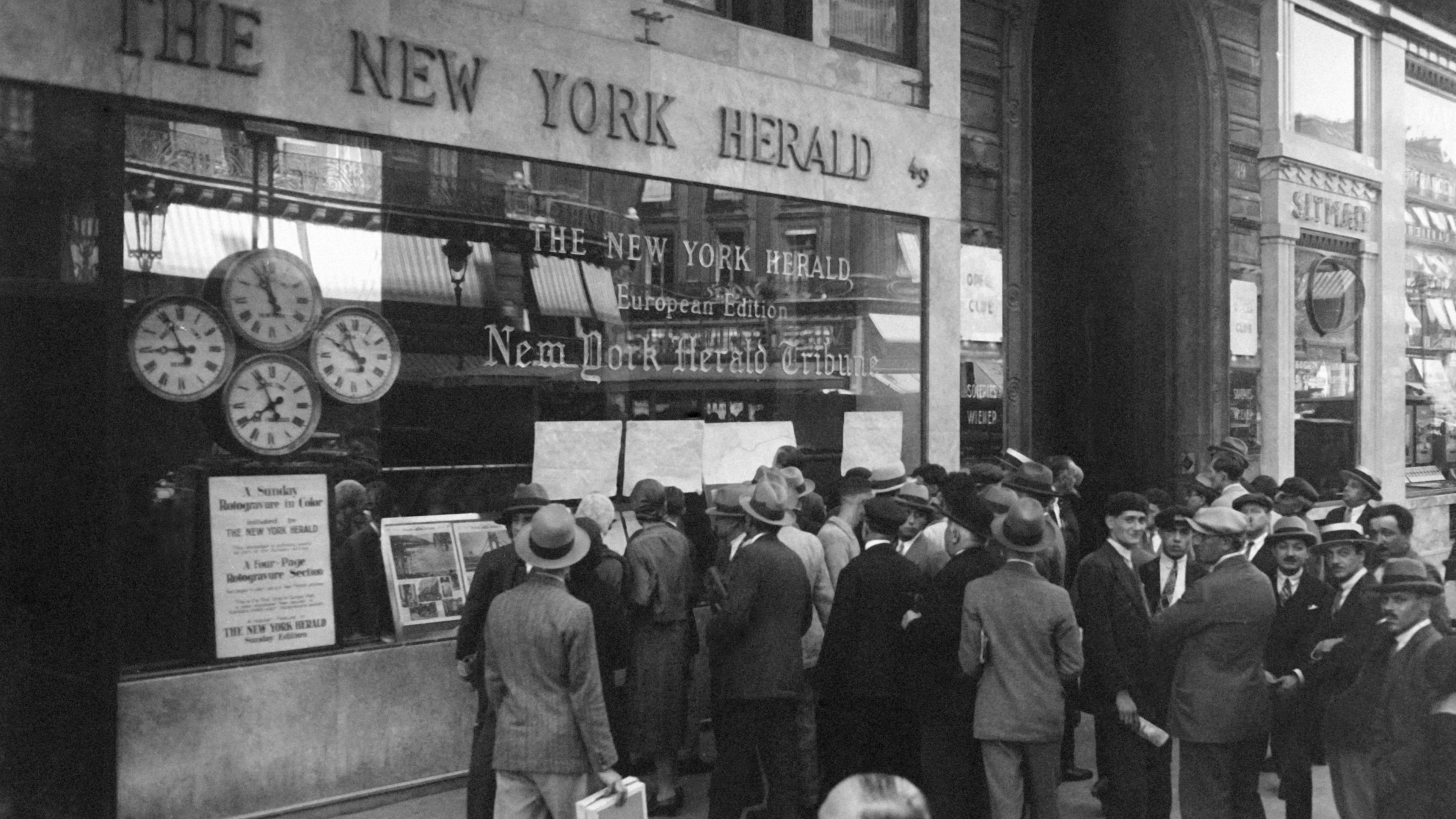

‘Mr Upton Sinclair speaks for a large body of opinion in America,’ Lippmann acknowledged in Public Opinion. Sinclair was far from the first or only critic who took his era’s media to task for what many perceived as its pro-business, anti-labour leanings. As the historian Sam Lebovic has argued, most early 20th-century commentators agreed that the major metropolitan newspapers served the interests of the elite.

But Sinclair’s The Brass Check went further, arguing that even liberal-leaning city papers systematically ignored or denigrated labour unrest and radical social movements. Sinclair believed that this was an inevitable result of the media industry’s financial structure. In the 19th century, most newspapers were party organs: funded by political machines and expected by owners and readers alike to adhere to their dogmas. By Sinclair’s time, though, a decline in partisanship and a rise in literacy rates had spurred the rise of a thriving commercial press. Increasingly consolidated under the ownership of a few very wealthy men, Sinclair believed this press was beholden to its owners’ class interests.

Newspapers’ claims of editorial autonomy defied what Sinclair saw as the power dynamics inherent to any industry. To start a successful newspaper, you must develop ‘a large and complex institution, fighting day and night for the attention of the public … [and] the pennies of the populace,’ the muckraker wrote in The Brass Check. ‘You have foremen and managers … precisely as if you were a steel-mill or a coal mine.’ Like steel or coal or meat, the news was a commodity, produced, like any other in a capitalist economy, by hierarchical organisations working on an imperative to maximise profit and squeeze labour. Only the most ruthless would survive. The Carnegies and Rockefellers of the media industry were the newspaper chain owners William Randolph Hearst, Edward Scripps, and the Chicago Tribune’s Robert McCormick.

Lippmann criticised what he saw as Sinclair’s reductive attribution of the media’s problems to ‘a more or less conscious conspiracy of the rich owners of newspapers’. Sinclair was, to be sure, unsubtle and somewhat conspiratorial, and it didn’t help his case that he devoted much of The Brass Check to hashing out personal grievances with editors. But Sinclair also got something that Lippmann didn’t want to admit: the agendas of a few men did shape the operations of complex organisations, if imperfectly, indirectly, and with inconsistent results. Newspaper owners, in Sinclair’s view, had no more or less power than any other bosses. They conveyed what and how their workers should produce by way of diffuse directives transmitted through layers of managerial hierarchy. The only source of their tyranny was what the 19th-century jurist Ferdinand Lassalle had called ‘the iron law of wages’.

.jpg?width=3840&quality=75&format=auto)

Walter Lippmann, c1930. Photo courtesy the Library of Congress

Lippmann thought that Sinclair’s attribution of media inaccuracy and bias to class interest was claptrap. He argued that Sinclair’s characterisation of journalism as prostitution – a ‘brass check’ was a token purchased by customers in a brothel – wrongly presumed that pure truth existed to be corrupted and sold. If it did, Lippmann argued, no one knew what it is. Lippmann’s experience in the First World War had taught him not only that organisations could consciously deploy information they knew to be false for the purposes of propaganda, but also that no individual possessed the totality of data necessary to understand fast-moving events in a complicated world.

It’s not that Lippmann denied that newspaper owners had class interests. He just didn’t think they were so different from anyone else. Steeped in the emerging literature of psychoanalysis, especially studies of mob mentality, Lippmann argued in Public Opinion that all individuals inhabited a ‘pseudo-environment’ shaped by their desires, fantasies and prejudices. If newspapers – commercial or otherwise – claimed to offer an account of the ‘facts’, they were offering only the facts that some compromised individual could see. Where Sinclair saw a power structure that gave a few wealthy men control over the production and dissemination of information, Lippmann saw a mass of confused, weak humans, none of whom could transcend the innate cognitive limitations of their species. Everyone’s view was incomplete.

Lippmann’s lynchpin argument against Sinclair went like this: if the problem with the press was capitalism, then wouldn’t the anti-capitalist press be free of fault? Lippmann pointed out that Sinclair devoted little attention in The Brass Check to socialist or radical newspapers. If he had, Lippmann reasoned, he would have been forced to admit that those publications contained their own set of biases, what Lippmann called ‘blind spots’. In fact, Sinclair didn’t ignore the socialist papers because he thought they were paragons of truth. He ignored them because he thought they had little impact compared with the commercial outlets that commanded much wider readerships. The socialist and radical press, whatever its blind spots, he might have responded, just didn’t have much influence.

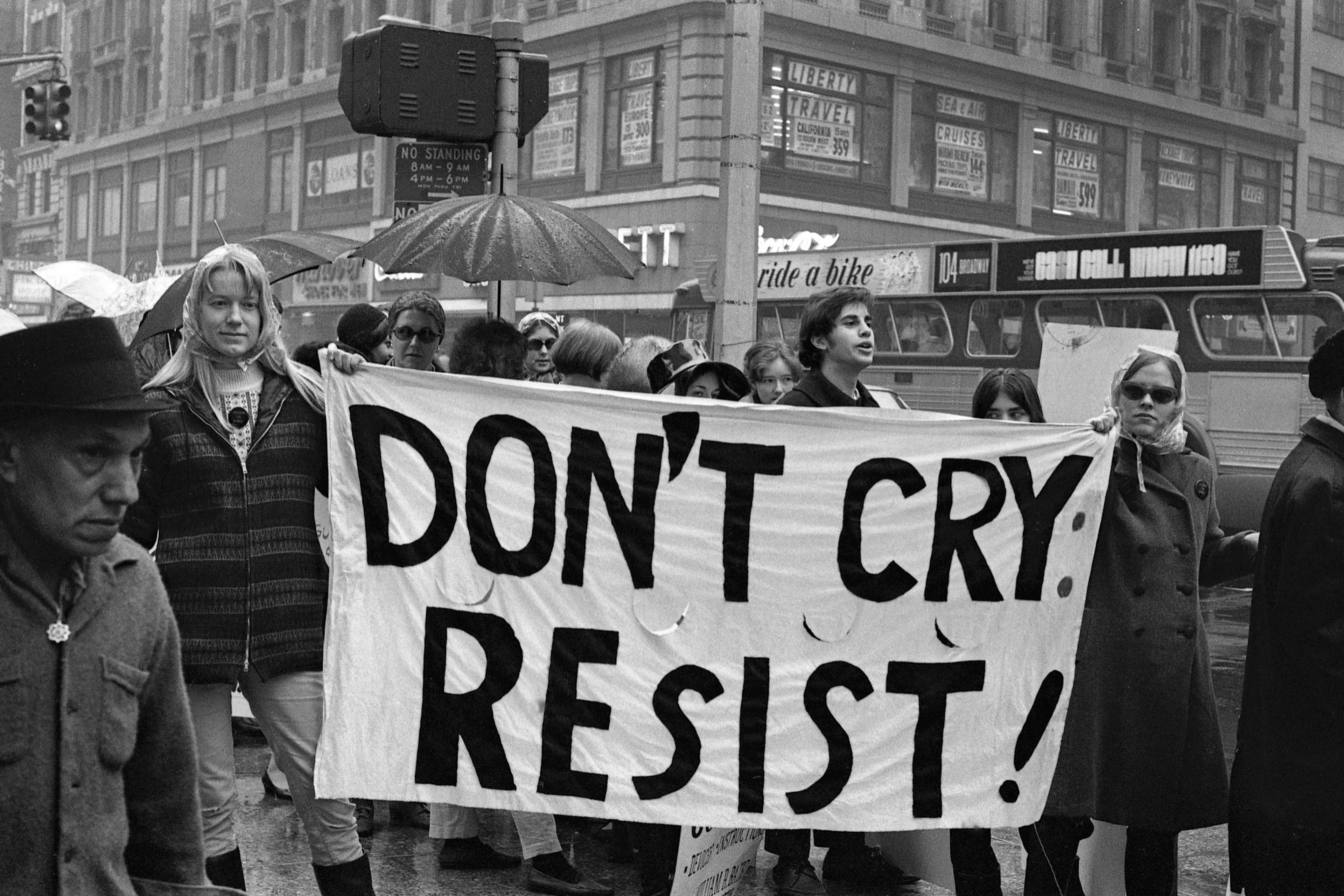

To address the outsized influence of newspaper owners, Sinclair had argued for shifting the balance of power within newsrooms. He encouraged journalists to form a reporters’ union to advocate for themselves as workers, with the goal of seizing editorial control. Lippmann, on the other hand, believed that the problems of journalism were the problems of human nature itself. He therefore maintained that hope lay not in political struggle within the press, but in the creation of new institutions that could transcend the press’s limitations through the cultivation of expertise.

In Public Opinion, Lippmann proposed replacing or at least supplementing the press with a network of intelligence agencies in government and industry, staffed by men trained in the new methods of data collection and analysis pioneered in the social sciences. When it came to the knowledge of experts, Lippmann’s cynicism about the limitations of individual subjectivity seemed to vanish.

For years after the publication of Public Opinion, Lippmann and Sinclair traded barbs in the press. Lippmann mocked Sinclair’s representation of himself as a ‘sublime and tormented hero’. Sinclair lamented that Lippmann had betrayed their once-shared socialism for the money and fame bestowed on him as a ‘clear-sighted spokesman of political and economic reaction’.

Initially, newspaper publishers and editors denounced both The Brass Check and The Public Opinion. Both books, after all, had attacked the very basis of journalism’s credibility. By the mid-20th century, though, many members of the media had embraced Lippmann’s critique and his agenda for reform. His Public Opinion became a staple in professional journalism schools that sought to create standards for a new, more expert and objective mode of reporting – a journalism more like a science. In those same schools, wrote graduate-cum-media-scholar Judson Grenier, those who read The Brass Check read it ‘rather surreptitiously’.

A better curriculum would teach the two books together. For all their differences, Lippmann and Sinclair both believed that it was not only possible but necessary to imagine a radically restructured press – one more beholden to the ideals of a democratic society than to the bottom line. Lippmann was right that Sinclair overestimated the extent to which bias and inaccuracy were the result of conscious intention. But Sinclair also saw something that Lippmann couldn’t, or wouldn’t: that psychology can’t explain whose biases get broadcast, whose ‘blind spots’ become the world’s.

Today, the media industry has consolidated under fewer owners than ever before; its labour conditions have grown dire. The undeniable expertise of many journalists isn’t enough to restore public credibility in the press. The political problem of the press will require a political, not merely a technical, fix.