For the ‘quantified self’ movement, the dream is better living through data analysis. You know the quantified self disciples: they’re the people dutifully recording their steps, sleep, sex, anything that can be turned into a number, and then gathered and probed using technology to reveal the secrets of health and happiness.

A major hurdle for anyone following this path is that the mind does not give up its secrets as readily as the body. It exists beyond the reach of Fitbit and Garmin and Whoop. But, today, perhaps, it is within the range of a suite of emerging apps that are based on artificial intelligence (AI) and large language models (LLMs).

These technologies promise to glean insights not just from heart rates and calories burned, but from our hopes and dreams. They are tools that claim to show what you might have missed about your life and how to make it all make sense. A way to be seen and known, by something trained on vast amounts of data, something possibly smarter than you. For this to work, the AI requires access to the place where the emotional self is recorded. It needs to read your journal.

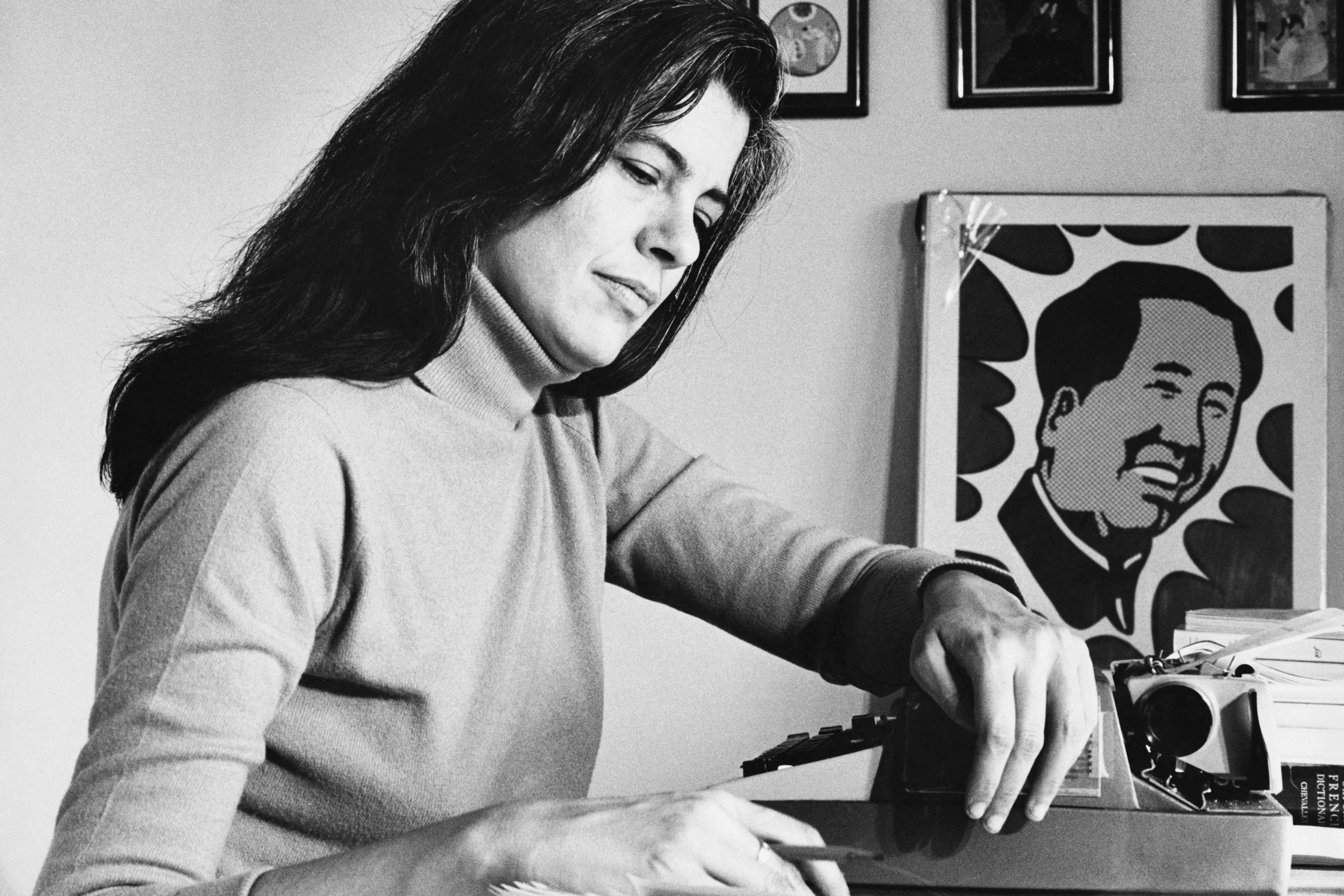

The journal, even back when it was a sheaf of paper covered in ink, was a precursor to the quantified self movement, according to Kylie Cardell, a researcher in autobiographical studies at Flinders University in Australia. She points to Benjamin Franklin, that lightning-defying Founding Father, who used a journal to keep track of his moods and failings, kept a list of goals, and then interpreted journal entries as data on whether he achieved them. Three centuries later, journaling has become a widely lauded self-help tool, supposedly capable of helping people achieve goals, unlock relationship problems, heal trauma, think better, and improve almost everything.

It’s now widely believed that ‘translating experiences into words helps us to understand the events better, and in so doing, it brings about a whole cascade of processes and changes,’ says James W Pennebaker, a psychologist at the University of Texas at Austin in the US. Thirty years ago, Pennebaker launched the growing body of research on the psychological benefits of ‘expressive writing’ that many of today’s diarising proselytisers take to heart (and mind, and habit). He believes that journaling is useful not only because of the act of translating, framing and discussing an experience, but because journals don’t invite judgment. ‘There’s a social cost in talking about deeply personal experiences,’ Pennebaker says.

The privacy of writing removes these costs, but it can be lonely to talk to yourself, never able to escape your own perspective. Therein lies the appeal of new AI-powered journals that promise to combine the candour of personal writing with the ability of machines to analyse text, all in the service of supercharging self-understanding and self-improvement. It’s better living through data analysis, using a new form of data this time around: the squishy subjectivity of inner experience. It’s quantified self for the soul.

Forgive me for calling the quantified self people ‘them’ when I could reasonably claim membership. I’ve long worn a Fitbit. I know what I’ve weighed every day since 17 May 2017. I maintain a colour-coded spreadsheet documenting the events of each day; last year, I used it as a weaving pattern and turned it into a data visualisation made of cloth. On the journaling side, I’m there, too: documenting my thoughts and feelings since 2004.

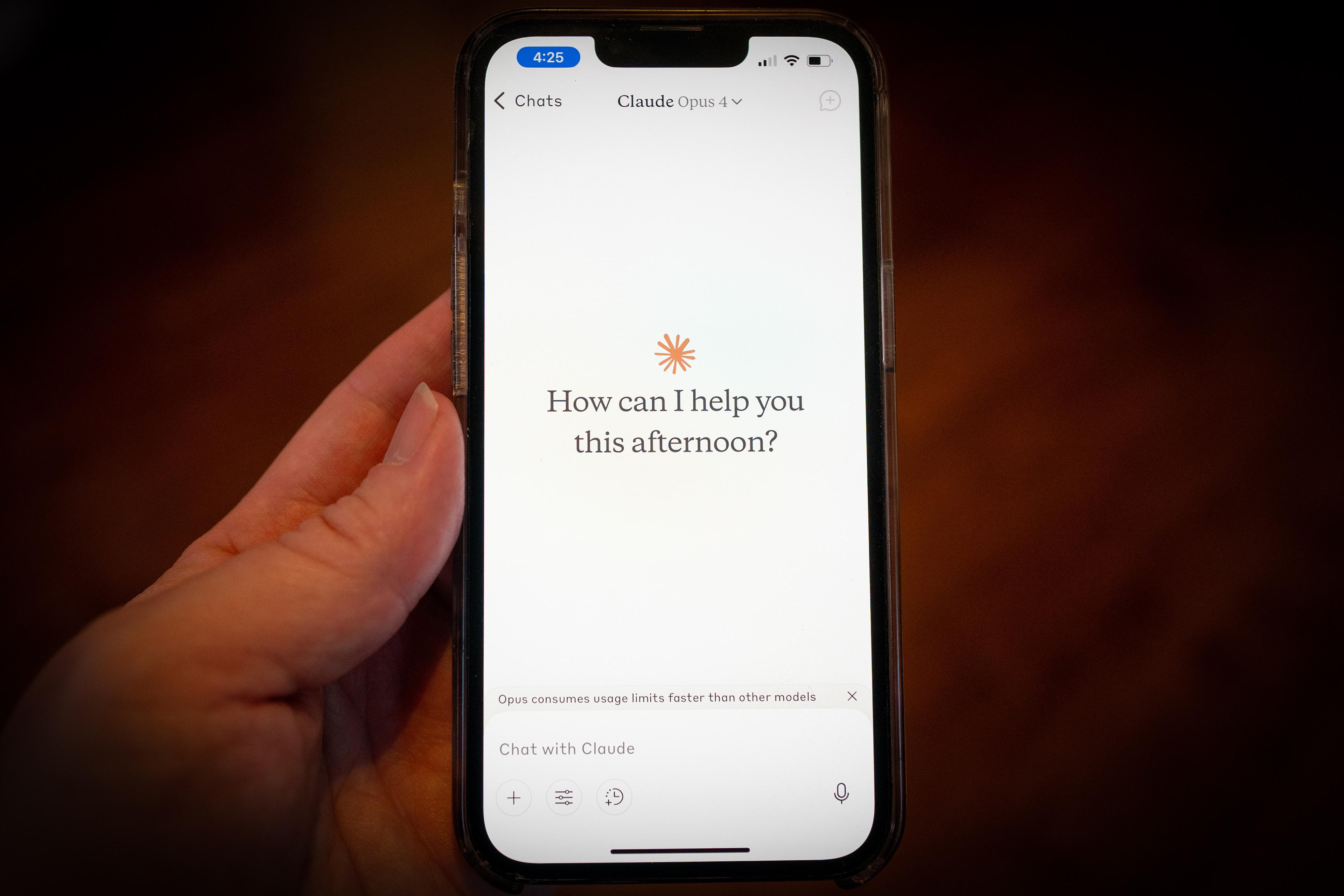

From this enormous corpus, I recently pulled an old entry in which I’d reflected on 10 years since I first moved to New York City. I pasted it into three AI-powered journaling apps – Rosebud, Insight Journal, and Mindsera – that offer a smorgasbord of tools, from AI chatbot mentors to personalised prompts and analyses of full entries.

Rosebud and Insight Journal sought to, in the parlance of therapy-speak, validate my experience. They congratulated me on my ‘intense’ and ‘incredible’ trajectory, and encouraged me to reflect on how I’ve changed and to ‘embrace’ my ‘journey of self-discovery and growth’. By prompting me to reflect more, these turned the isolated act of journaling into a social experience like a session of therapy with a checked-out chatbot.

Despite the supposed potential of advanced intelligence, the responses were canned

By far the most sophisticated responses came from Mindsera, though it left something to be desired. It claimed my writing contained 50 per cent anxiety, 30 per cent fear, and 20 per cent love – based on this, it offered what seemed like a generative-AI horoscope, including lines about how I am ‘capable of feeling intense love, but also fear and anxiety’.

Other things I apparently am: resilient, capable of making difficult decisions, possessed of the courage to take risks and make changes in my life. ‘You are also capable of being vulnerable and open to new experiences,’ Mindsera informed me. ‘You are thoughtful and reflective, and have a strong sense of self-awareness.’

These blandishments seemed like the Barnum effect in action, technically responding to my words yet hardly more sophisticated than the cold reading of a psychic. Despite the supposed potential of advanced intelligence, the responses were canned, unintelligent.

Perhaps I was being unfair. It’s a tall order to expect incisive analysis from a few posts.

The true value-add comes in crunching thousands of entries and teasing out connections from a more holistic portrait, and LLMs become more accurate when they have more to learn from. The writer Dan Shipper did this by building his own journal bot, uploading 10 years of entries and asking questions. Though some responses were repetitive and unhelpful, asking why his relationship ended ‘produced incredible results – but isn’t something I want to put on the internet.’

Shipper’s understandable reluctance to publicise that response is the same reason I was hesitant to share too much with commercial technology I don’t control. Despite also having thousands of entries on hand, privacy worries held me back – ironic, given that privacy is one of the benefits of journaling. The possibility of data breaches and policy changes made me worried about analysing either a large volume of entries or anything truly sensitive.

I was impressed by the app’s willingness to point out the less appealing parts of my nature

In the end, I decided to upload all entries from a single, highly significant month: June 2013, the same month I moved to New York, and the month that I started living with my then-boyfriend. I wrote nearly every day then, meandering, anxiety-soaked ruminations, aware of my catastrophic insecurity, fixating and unable to stop.

This time, Mindsera took off the kid gloves. Nearly every analysis praised my self-awareness, but it also noted that (11 years ago) I had ‘a difficult time accepting that others have a past and may have loved before you’. I ‘crave reassurance and validation from [my] partner, which can sometimes lead to feelings of disappointment or insecurity when they don’t meet your expectations’. I was told I am ‘constantly anxious and worried about the possibility of his feelings fading or changing … You have a hard time accepting that these intense emotions cannot last forever and struggle with the idea of them dulling out.’ Though some of the insights are not as perceptive as they might seem here – at several points, I had written a similar analysis in the journal entry itself – I was impressed by the app’s willingness to point out the less appealing parts of my nature.

Inspired by Shipper, I then used a Mindsera tool that let me ask why, based on its overall analysis of my journal entries, this relationship had ended. The answer wasn’t incredible, but it wasn’t mindlessly puffing me up either, and some of what it said struck a chord. Among the phrases it used were ‘feelings of hurt and inadequacy’; ‘struggle to reconcile personal flaws with external perceptions’; and ‘profound internal conflict’.

Reading this second batch of answers did provoke an ‘aha’ moment of familiarity. But I might have been experiencing what Jill Walker Rettberg, professor of digital culture at the University of Bergen in Norway, calls ‘dataism’. She points to a study of people in Finland who were tracked to create ‘data doubles’, or versions of themselves assembled from detailed measurements. In these cases, when shown the data, people might ‘edit their experiences and negotiate with the data’ she says. Yes, they might say: I remember now, I was feeling stressed out that day I had the higher heart rate. They are persuaded to ‘retell the narratives of their life to fit the data’, instead of trusting themselves. I might have been falling into a similar trap.

Seeking outside authority is as old as Delphi; believing that what others tell us about ourselves is true is a constant temptation. But a modern, specific danger is imbuing such judgments with extra authority because they come from data and algorithms.

Retelling narratives to fit the data, or letting the machine drive the narrative entirely, could shape reality in potentially harmful ways, especially if the analysis is specious. Mindsera told me that my original post about New York City contained 50 per cent anxiety and 30 per cent fear. Months later, I re-analysed the same post several times, and this time it came up with ratings such as 40 per cent nostalgic or 40 per cent overwhelmed, revealing the false precision of such numbers. In its analysis of the relationship entries, Mindsera suggested that I shouldn’t give up trying to make things work; 11 years later, I can assure you that this relationship was not worth saving.

Despite these shortcomings, I still find myself drawn to the AI mirror and to discovering how a machine will interpret my inner self. Although Pennebaker has concerns that these tools don’t provide enough information about the founders and their backgrounds, he too thinks AI developments in this area can be ‘fascinating, and wonderfully exciting’ – he can see them especially helping those who are socially isolated.

We should also be realistic about the difference that journaling, on its own, can make

The key is to remember that the self is wild and messy, and we should avoid outsourcing all interpretation and mistaking statistical analysis for divine revelation. This holds even as the technology improves and we are increasingly tempted to appeal to the numbers and ‘superior’ intelligence. It would be dangerous to erase ourselves – that is, give away our own privilege of interpretation – in the quest for self-improvement.

We should also be realistic about the difference that journaling, on its own, can make. The most disappointing part of these tools was that, even when the analysis seemed accurate, the actionable suggestions consisted of obvious advice that applied to nearly any situation. Reflect. Remember your values. Set boundaries. Calm down. Communicate openly. Have realistic expectations. Talk to a friend. Seek professional help.

But I’ve since realised that, even if I had gone to a professional therapist, their suggestions likely would also have involved reflecting, remembering my values, setting boundaries, and so on. In many situations, there’s little else that anyone, friend or parent or professional, can advise rather than the obvious, and to ask for more from AI at this stage seems unfair. Even for Pennebaker, who knows as much about the benefits of expressive writing as anyone, the idea is to write occasionally when you need it, not necessarily journaling or turning inward as a habit. ‘I do think too much introspection is probably not that healthy,’ he says, because it can turn into rumination.

That’s the most important lesson from my time experimenting with AI journals. AI-powered or not, introspection can take us only so far. What I needed to change my life was not more analytical firepower, but the maturity and strength that comes from age, friends, better relationships and bravery – all experiences in the world outside my head.