The day I turned 45, I bought an expensive pair of sunglasses. The priciest shades I’d ever owned, they were branded with a ‘handmade’ stamp and had wooden frames. Almost every fur-clad señora in Madrid wore a similar pair, and for months I’d been gazing wistfully at them as they passed me on the street. Yet my guilt muscle would twitch even thinking about the price tag. The most I’d ever spent on a pair of sunglasses before was $20; paying several degrees more was unthinkable, excessive and, frankly, completely outrageous. How could I possibly justify the expense?

Then the morning of my birthday came. In giddy anticipation, I reached under the bed. Feeling around with my left hand, I came across an errant sock, a few dust bunnies, and our dog’s tennis ball. Excitement somewhat dampened, I swung down my head to look. A lonely gift bag sat just outside my reach. I slid it towards me and fished out a card. ‘Happy Birthday, Mommy!’ it read.

In our family, the tradition of leaving birthday gifts under the bed goes back to my childhood. Spent in Brezhnev’s Soviet Union, it was an era so bleak for consumer goods that parents had to invent ways to pimp up their kids’ presents. My mother chose the element of surprise. On the night before my birthday, after making sure I was asleep, she’d sneak into my bedroom and stack newspaper-clad packages under my bed. Wrapping paper didn’t exist in the USSR, so my new pencil-holders, bars of soap appropriately named Podarochnoe, or ‘gift-destined’, and a tome or two of Tolstoy always came swaddled in old issues of Pravda and Izvestia.

The ritual hooked me and, though my mother discontinued it when we left the USSR, I brought it back as soon as my daughter was born. Her gifts were infinitely better than anything I ever got, but I wanted her to experience the birthday surprise I loved as a child. The tradition became a hit, and soon my daughter was putting the cards she made for me under my bed too.

The small gift bag I fished out the morning I turned 45 was from her. Now a teenager, she recognised that cards alone weren’t sufficient. But her time was limited. She had homework to ignore and Instagram to maintain, so her go-to strategy for ensuring I had a gift was to make something at the last moment. The night before, she’d stayed up late to turn a glass I’d recently bought at Zara Home into a candleholder, à la Romero Britto. She then drew lots of hearts on a card fashioned out of A4 paper, stuck it and the gift into a bag, and left that under my bed.

I loved that candleholder and I loved that, at 14, my daughter was still keeping the under-the-bed tradition alive. What I didn’t love, however, was that there was nothing else under my bed. No other wrapped package, no card with a gift certificate, and not even a ‘your present is held up at customs’ note from my husband.

It wasn’t that he’d forgotten. Remembering dates was never his problem: he always called family members on their birthdays, sent timely gift certificates to his nieces and nephews, and purchased matzo for the house well in advance of Passover. The guy could plan if he wanted, but this ability didn’t extend to planning for my birthday. Almost two decades of marriage and an annual barrage of hints in the weeks and days leading up to my special day – and he still didn’t get the importance of being prepared for it.

Growing up in 1970s and ’80s Moscow, there were a few things of which I was certain. I knew that on 7 November, the anniversary of the Russian Revolution, instead of school lessons, we’d watch a direct transmission from the parade in Red Square. I knew that on 22 April, Lenin’s birthday, I’d don white tights, stick a large white bow in my hair, and put on a white apron over my brown dress to stand guard in front of his bust in sombre silence. And I had no doubt that on 25 April – my birthday – I’d be celebrated by family and friends with a grandiosity to rival both of the above.

The birthdays of my childhood required planning akin to the Communist Party’s five-year plans

In the Soviet Union, birthdays were sacred. Observed with a fervour that other countries reserved for Christmas, they involved everyone in your immediate circle, and made you feel so special a Tsar would be envious, had the Bolsheviks let him live. To give a gift, however small, was a must – you’d never wish someone ‘S dnem rozhdeniya!’ without a present to accompany that wish. After I landed in the US, it took me a few years to stop waiting for my new American friends to open their bags and produce a gift as they said ‘Happy Birthday!’ Why should I be grateful for those greetings, I thought with indignation. They require no thought or preparation whatsoever!

Preparation was key – it showed that people took the time and that they cared. To make my birthday special, my parents nurtured connections in warehouses that distributed clothing from East Germany. My grandfather saved rations of caviar from his veteran’s package to get me the very first Soviet-made tape recorder. My grandmother worked overtime seeing patients so that, whenever one travelled abroad, she could ask for a foreign deodorant, a bottle of perfume or a jar of body milk. The birthdays of my childhood required planning akin to the Communist Party’s five-year plans. For me, that planning meant love.

When my husband and I met – a week after I arrived in the US – I introduced him to the culture I’d left behind. I taught him some Russian, demonstrated how to chop vegetables for Olivier, the Russian potato salad, and initiated him into Soviet rock. Indoctrinating him with reverence towards birthdays took some effort, but once we started dating he caught up. There were flowers and fancy-for-students restaurant dinners at the beginning of our relationship; cute pyjamas and weekend trips after we got married; surprise parties and theatre tickets when our years together reached double digits. Then he started running out of ideas.

‘It’s too much pressure,’ he complained. ‘Valentine’s Day, your birthday, and our anniversary come in too quick a succession.’

‘Your birthday is a week before Valentine’s Day and you don’t see me complaining,’ I replied.

As the years went by, he complained of more and more pressure, and I dropped more and more hints. I left newspaper clips with concert announcements on the kitchen table, I pointed out jewellery I liked whenever we went shopping, and I complimented flower arrangements if we walked by a florist. Dropping hints was my way of ensuring he’d still plan and prepare. Because, if no one makes an effort on your behalf, does your birthday actually happen?

By the time my 45th birthday approached, I’d outdone myself. Because it was a kruglaya data, a milestone birthday, I dropped enough hints to rival the number of soldiers in one of the Red Square parades of my childhood. When no gift from my husband materialised under my bed, I felt devastated.

‘Why don’t you buy your own gift?’ my daughter asked me when she came back from school and saw me sulking on the sofa.

‘It’s my birthday,’ I said. ‘I want to feel special.’

‘Don’t wait for others to make you feel special,’ she said. Then she shrugged matter-of-factly. ‘Do it yourself.’

The belief that someone else held the key to my happiness wasn’t making me feel special

I looked at my daughter. Was her wisdom a testament to my stellar parenting, my not so parent-like tantrum, or both? And, more to the point, was she actually right? What was I doing holding my husband responsible for my birthday happiness? That was so 1970s Moscow.

I got off the couch, washed my face with cold water, and went for a walk to clear my head. Relying on my husband – or anyone else for that matter – for my birthday, I decided, had to stop. The waiting, the expectation, the belief that someone else held the key to my happiness wasn’t making me feel special. It was making me want to outlaw birthdays and gift-giving altogether.

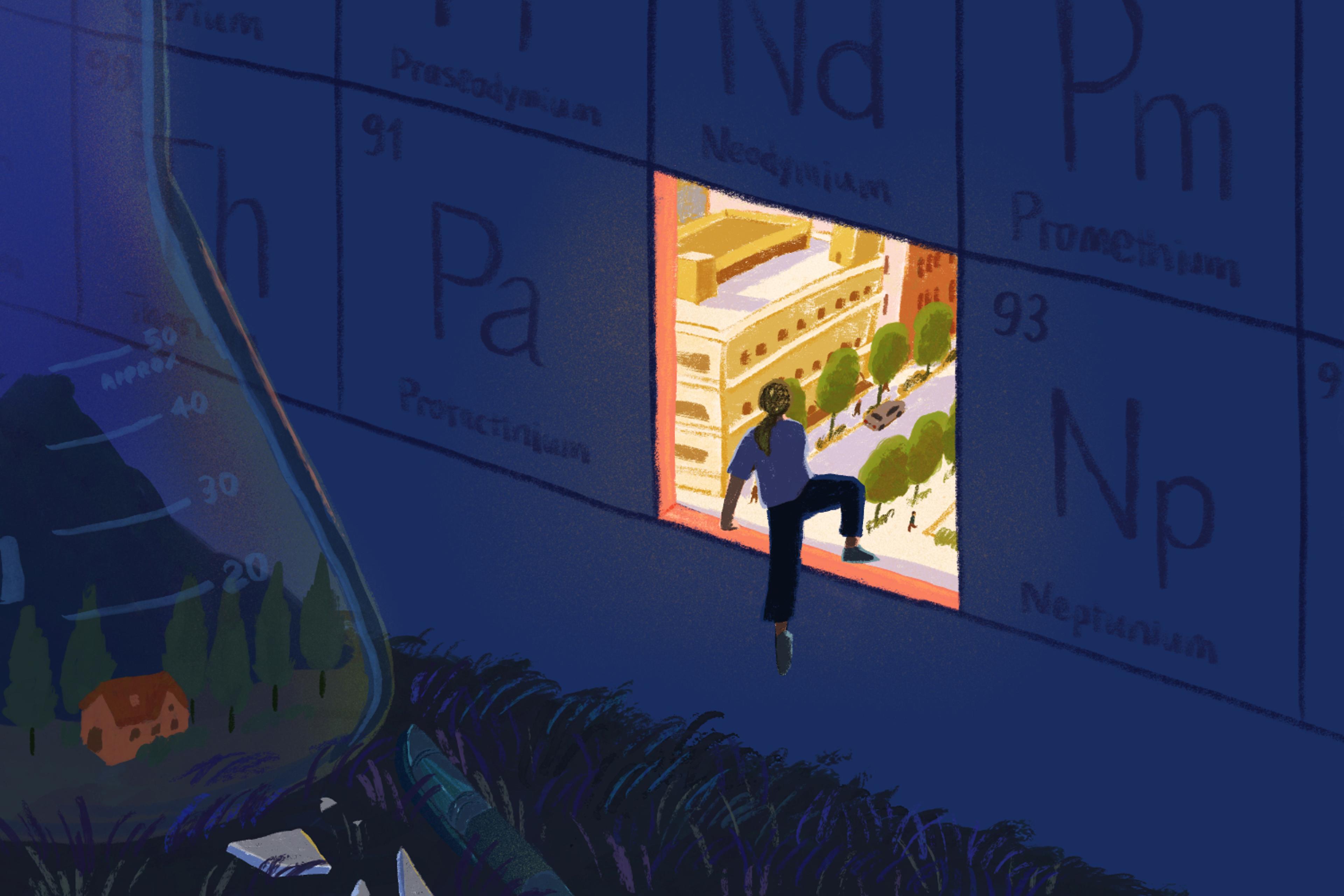

Turning the corner, I passed a store with a window display showcasing the sunglasses I’d lusted after for months. I slowed down. If outlawing birthdays wasn’t an option, should I consider a less severe alternative? Should I, gasp, buy my own gift?

I walked in.

In the Moscow of my childhood and adolescence, buying your own present meant no one cared about you enough to give you something. On the day I turned 45 and the moment I signed a credit card receipt with too many digits, I concluded that was foolish. For my birthday to happen, I didn’t need someone else to make an effort. If planning indeed meant love, I could very well do that planning myself – one special birthday at a time.