About 5,000 years ago in ancient Mesopotamia (roughly corresponding to modern Iraq, Syria and southeastern Turkey), deceased ancestors were buried under the floors of residential houses. These family funerary crypts were usually planned before the construction of houses because the ancestors represented the spiritual foundation of the house. The crypt was visible on the floor by a tombstone that would have been reopened whenever necessary to bury the remains of the newly deceased who, upon death, had transitioned into the realm of the ancestors. The reopening of the tombs in the home must have released a strong odour that reinforced the fear of and attachment to the spirit of the ancestors.

Even if the idea of burying ancestors underneath your house can appear peculiar, the sensorial attachment to ancestors that marked ancient Mesopotamian societies is not that different from our modern relationship with the deceased. In fact, when we think about our beloveds that have departed, it is the smell of their homes, the visual record of their presence in photographs, the sound of their recorded voices or the taste of their favourite foods that allow us to revive and keep alive their memory so that they remain present in our lives. It is through sensory experiences that the memory of dead ancestors enables communities of the living to overcome the sorrow created by such loss. These sensorial memories make the experience of grief bearable for the individual. The psychological disarray created by the physical absence of beloveds can be experienced through the creation of loci memoriae (memory places) within the house which, in certain cases, resemble altars. These altars can be used as locales for reviving memories through the enactment of rituals based on a sensorial remembrance of the ancestors (eg, lighting a candle, singing a song, burning incense, displaying pictures, sharing food or beverages, etc).

Such a sensorial and material vision of how the community of the living relates to dead ancestors was even stronger in ancient times. Before modern devices allowed memorialisation through the use of photographs or videos, the physical presence of their bodily remains was the only proxy for practising rituals of remembrance. In particular, the history of the ancient communities that inhabited the Middle East from prehistoric times until the arrival of Alexander the Great gives us a clear view of the techniques that were used by the living to stimulate a sensorial memory of the departed ancestors. This perspective is mostly based on the archaeological relics of these rituals, but – starting from the first forms of writing about 5,500 years ago – also on cuneiform written sources that describe such practices.

In addition, when – about 12,000 years ago – the first communities of farmers initiated a revolutionary process that led people to settle down in the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East, this change brought the formation of the first villages with a shift from a hunter-gatherer to an agropastoral form of economic subsistence. The spiritual presence of the ancestors became essential for developing what the archaeologist Vere Gordon Childe named the ‘Neolithic Revolution’. Such a transformation in the social and economic organisation of these communities created the need to solidify social ties, and thus selected individuals (ie, probably spiritual leaders) became ideological references who, when deceased, were materially transformed into a physical presence of ancestral power in the earthly world.

In this process, the skulls of these individuals were displaced from their bodies, followed by the decoration of the skull’s surface with plaster and pigments, while shells were inlaid into the eye sockets. These reconstructed heads – the material embodiment of the spiritual essence of the deceased’s soul – were placed within ritual houses in order to be visible to members of the community seeking to connect with the spiritual power of their ancestors in a form of animistic religiosity. These skulls were also probably physically and ceremonially handled, similar to later Neolithic examples found in the dwellings of Çatalhöyük in central Anatolia. At the end of their period of use, these primeval tridimensional icons of spiritual forces lost their function and were buried together in pits as a sign of respect for their inherent power, only to be recovered by archaeologists millennia later, who then transform these objects of primordial religions into museum objects.

The incredible power of the relics of human beings to stimulate a sense of belonging in the members of a given family or community continued to be strongly present in the tradition of ancient Near Eastern societies. This devotion toward dead ancestors carried on even when polytheism arose in correspondence with the emergence of the first cities of the world.

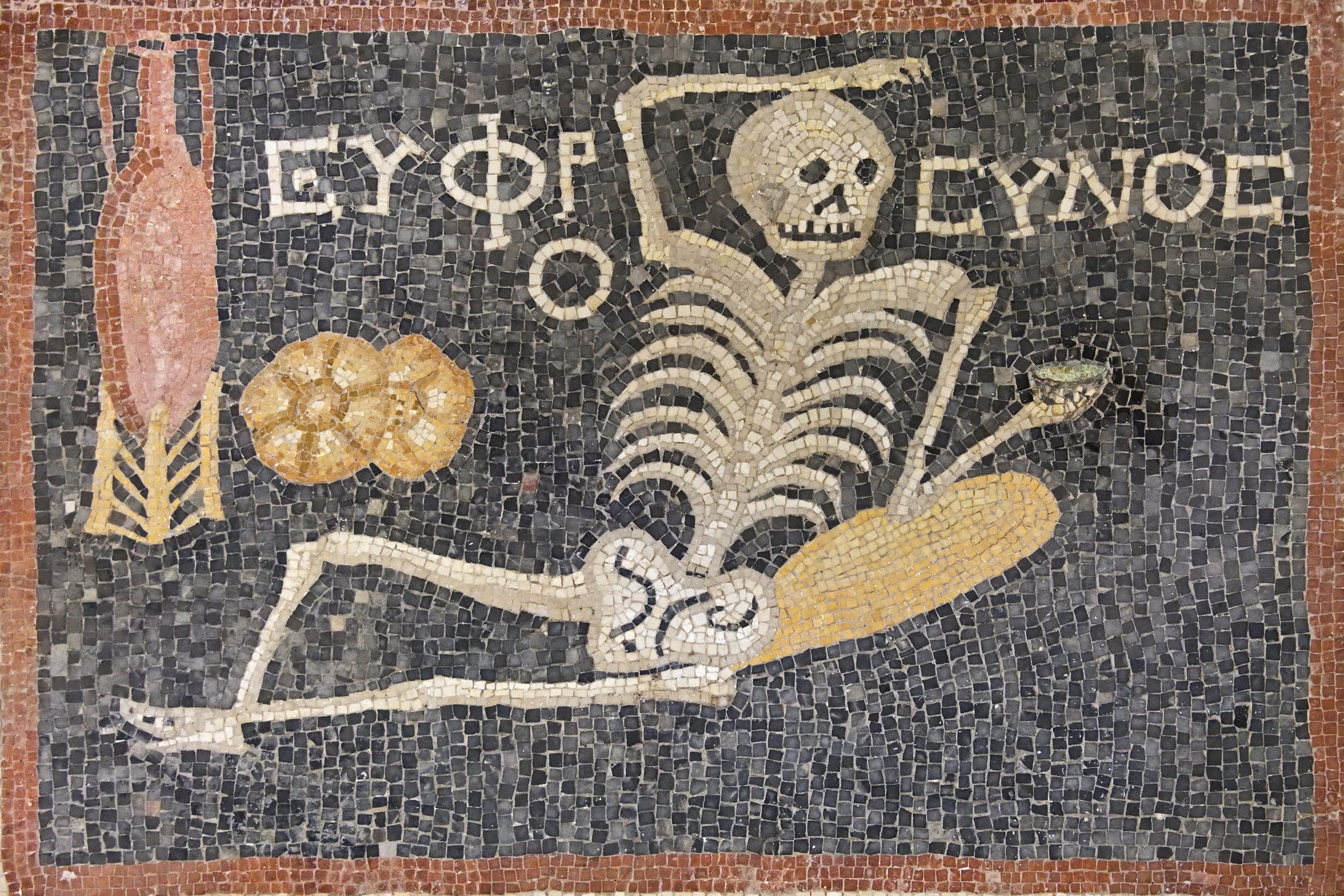

This sensorial aspect associated with tombs built inside buildings is even more evident in the extraordinary royal hypogeum, a subterranean chamber that was located underneath the 2nd millennium BCE palace of Qatna, western Syria, which was excavated by a Syrian-German expedition in the 2000s. Here, the archaeologists were able to reconstruct all phases associated with the treatment of the selected corpses, as well as with the celebration of feasts associated with a possible cult of the dead ancestors. Such a ceremonial process, called kispu, was also described in texts written in the cuneiform script of the ancient Semitic Akkadian language. The kispu ceremony aimed at reviving the memory of dead ancestors through the recitation of their names and the sharing of food and beverages with them.

At the royal hypogeum of Qatna, the ceremonies must have involved all of the senses, and the people who gathered during these ceremonies must have been intoxicated through the use of opiates, as highlighted by the presence of carbonised remains of these plants inside the impressive crypt excavated in the natural bedrock. However, it was the incredibly rich goods found inside the chambers that emphasise the important role played by the ancestors in creating a mnemonic reference to the world of the dead by the community of the living. In particular, the two basalt seated statues at the entrance, each holding a cup in one hand, both reinforce the commemorative role played by this locale and serve as a reference to the ceremonies enacted in it, which invoked the memory of these individuals.

The tradition of burying certain ancestors within houses, and especially underneath palaces, continued throughout the 2nd and 1st millennia BCE, as testified by the discovery of monumental hypogea in the royal palaces of the Assyrian kings. More specifically, the kings were buried in the Old Palace of the first capital, Assur (northern Iraq). However, the queens were buried, together with rich objects such as gold jewellery, under the floors of the residential sectors of the palace built in the 9th century BCE by king Ashurnasirpal II in the newly founded capital Nimrud (or Kalkhu), located about 30 km south of the modern city of Mosul in Iraq.

Even though the idea of inhabiting a place containing the remains of dead beloveds, or a home with a grave dug into the floor, which was periodically reopened to bury newly deceased individuals, and which must have contained decomposing corpses, appears strange and difficult to imagine in today’s world, it is helpful to envision the needs of a society that lacked the support of photographic or other visual means for remembering dead ancestors. With this in mind, the physical presence of their remains within the house represents a continuous connection that served the purpose of strengthening familial ties, especially in moments of socioeconomic transformation during which the memory of the ancestors represented a source of guidance to support the household. Thus, this presence was strongly validated by the sensory experiences of the living which – through the sight of the tombstone, the smell of the decomposing corpses, the taste of the foodstuff and drinks used to commemorate them, as well as the sound of their names in recitation – would have provided a continual reference to the ancestors’ idealised presence within the world of the living, making them still a vital part of the community.

Obviously, it is a difficult task for curators to reproduce such a sensorial environment in museums or archaeological parks in order to make the general public part of an immersive experience that may revive the experience of ancient people. But innovative technologies (for example the use of the Metaverse or machine olfaction) can support a future for a sensorial experience that will help bring to life the memory of ancient ancestors.