The neurodiversity movement frames different ways of thinking and perceiving the world as part of the naturally occurring spectrum of human development that comprises neurotypical and atypical (neurodivergent) variations. While the term ‘neurodiversity’ is currently used in reference to a wide array of neurodevelopmental and mental health conditions, it was originally coined in the 1990s in the context of advocacy for individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

I am a woman in academia, an entomologist, and I was finally diagnosed with ASD at the age of 30. In true millennial fashion, it took a TV character, a TED Talk, and a handful of online quizzes to finally seek out a diagnosis and untangle what was going on inside my divergently wired head. The diagnostic road was costly and long, but I got there in the end. In this respect, my story is like that of many late-diagnosed autistic women. We collect all sorts of labels – introverted, anxious, depressed, geeky – as we fall through the cracks of a system primarily designed to evaluate little boys. But I was probably luckier than many, because even before I found recognition and identity within the ASD community, one of those labels provided me with a great sense of belonging: I was the Bug Girl.

In fact, I’ve spent my time watching insects and soaking up scientific jargon since kindergarten. As a kid, my idea of fun was poring over my mother’s medical textbooks or feeding the ants on my grandmother’s bathroom floor. My parents proudly called me an early reader, a gifted child, while grandma shook her head at my delight in attracting vermin. When the other kids were interacting in social ways I could not quite comprehend, the insects and their tiny movements made perfect sense to me.

Why was it ‘inappropriate’ for me to sit in the corner and draw while the other children played? Why was it ‘rude’ to speak up when the teacher falsely called a pony a ‘baby horse’? Sprawled out on the warm bathroom tiles, I witnessed the ants diligently scouting for crumbs and exchanging their flitting antennal greetings. Those were the things I could understand, that I could lose myself in, allowing me to ignore the confusing humans for a while. As alienated as I continued to feel from most of society, the entomological world was where I would eventually discover that fabled sense of community, where I would build my career and make my emotional home.

Today I am privileged to work at an academic institution where diversity is valued in all its human and natural variations. Therefore, when I was finally ready to cast off the exuvia of secrecy about my diagnosis, my disclosure did not lead to any of the awkward questions or disbelief I had been afraid of. Instead, someone said: ‘Most entomologists I know are a bit… weird.’ And I had to agree. I have no doubt that my autism spectrum condition is somehow related to this persistent interest in all that creeps and crawls. And judging by many conversations with both my neurodivergent peers and fellow entomologists, I am far from alone in having made this connection. Neurotypical insect aficionados certainly exist, as do autistic people who do not care for bugs at all, but the overlap between the neurodivergent and entomological communities seems too large to be rooted purely in chance.

Somewhat unsurprisingly, my search for formal studies on the topic yielded no results. It’s a deplorable fact that autism remains scientifically most interesting when it comes to ‘dealing with’ or ‘preventing’ it – us – somehow. Our daily lives, our intense passions, interests and talents, our own stories in our own words, are still so rarely the subjects of enquiry. In the hope of inspiring further academic research that centres on autistic professionals and hobbyists actively participating in entomology, I have attempted to highlight the main phenomena that might serve as points of connection linking neurodivergence and interest in insects:

1. Sensory stimulation

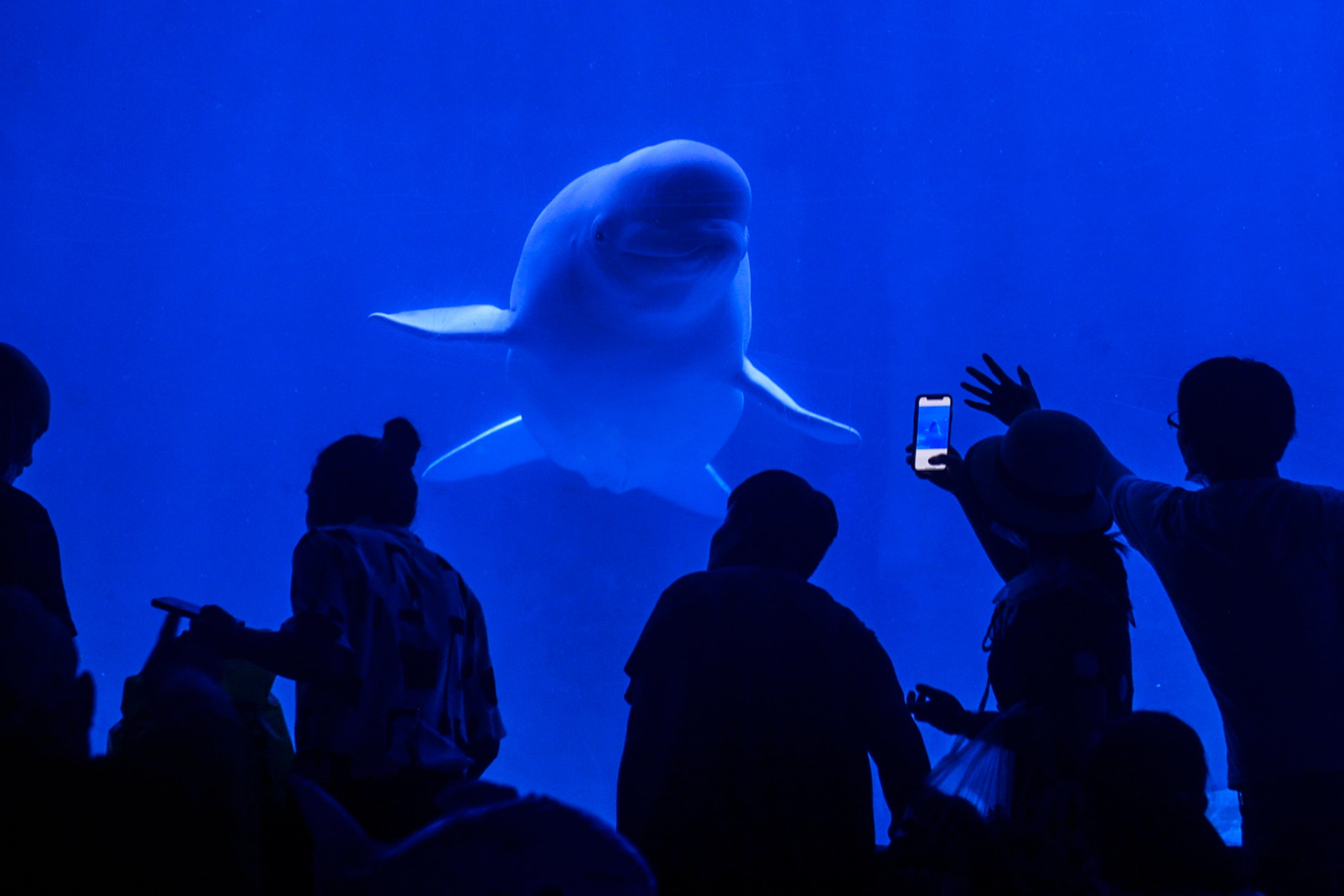

Autistic senses are special – often hypo- or hypersensitive in comparison with the average neurotypical person – and this influences whether we seek out or shy away from different components of our environment. Fittingly for an entomologist, I find joy in colours, shiny things, and noticing the small details missed by others. Sharp little tarsal claws, the glistening facets of a compound eye, segment borders with fine bristles, or the iridescent hue of an ant’s integument – they all appear like magic out of the blurry mess when the microscope finds its focus.

But insects are not only a feast for the eyes, they provide great tactile stimuli too – the surface of a water beetle’s elytra (forewing), impossibly smooth like plastic, or the fuzzy pelt of a bumblebee. We like to let kids touch them at science education events and watch how the pleasant textures spark joy in their eyes, instantly replacing the hesitation and fear of only a moment before. And if our senses are stimulated just right, the road to hyperfocus is paved: in that all-consuming blissful trance, the world becomes small and quiet at last. Hours spent measuring multijointed legs or putting tiny paper tabs on pins can whiz by as the rest of the world dissolves. Eventually, only the morphological structures permanently burned into our retinas and the calluses on our fingers serve as reminders that there can be too much of a good thing.

Far away from the wondrous world of shiny insects, the clinical literature on autism has ascribed this delight in detail to so-called ‘weak central coherence’. This refers to the supposed inability of autistic people to readily perceive the larger context of a structure or situation. However, studies have yielded inconclusive results as to whether this common affinity for the small and intricate is actually due to decreased perception of context or rather a heightened ability to discern details, when compared with the neurotypical population. As with so many other aspects of autism research, future studies that take into account our own lived experiences might help shed more light on the matter.

2. Classification celebration

The neurodivergent mind often has a special affinity for categories. It thrives on neat boxes, labels, and names to go with things. It helps us make sense of a world that so often appears confusing, overwhelming and chaotic. I like to imagine that my brain resembles the insect collection at the Natural History Museum, and therefore feels so very at home there. It’s a little old-fashioned, quite resistant to change, but – beneath a layer of clutter and dust – usually well-ordered and full of obscure Latin words. It has filed and compiled the labels of wonderful things, such as the parts of an insect leg: coxa, trochanter, femur, tibia, tarsus. In fact, the entire field of taxonomy is a treasure-trove of categories in itself: Animalia, Arthropoda, Insecta, Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Formicinae, Camponotini, Colobopsis, Colobopsis truncata – a little plug-headed ant. Its name is the smallest in a set of nesting dolls, one within the next, each with its own label. What could bring a lover of order more joy than that?

Unfortunately, conforming to these almost stereotypical characteristics of exhibiting a detail-oriented nature and talent for categorisation also comes with its own pitfalls. While many employers still consider individuals on the autism spectrum difficult to integrate into the workforce, leading to high rates of unemployment, we quickly become ‘assets’ or ‘valuable team mates’ as soon as our special interests or abilities are somehow economically convenient. But contrary to popular belief and media representation, we are not all equipped with superhuman, easily commodified computer-programming skills. We are not in fact magical savant robots perfect for repetitive assembly-line jobs considered too dull for neurotypical workers. We are just humans, some of whom happen to like repetition, mental or physical boxes, or small shiny animals.

3. Critter camaraderie

Below is the last stanza of a little poem about looking at ants under a microscope that I wrote during my PhD, and it ended up on the first page of my dissertation. ‘Dedication’, I called it:

To my companions on this path

Be they with six legs, four or two

It takes brave madness if you love

The small and strange – this is for you!

Let me point out the somewhat heavy-handed symbolism here. The small and strange – those are the ants, tiny, underfoot, easily ignored, always ready to ruin your picnic. But that is also me, 5 ft 2 in, bugs on my socks, fingers fidgeting, eyes darting. As the self-described neuroqueer author M R Yergeau put it so chillingly in Authoring Autism (2018), ‘autistics are [like] insects’ under the psychoanalytic gaze. At least, it feels like that sometimes.

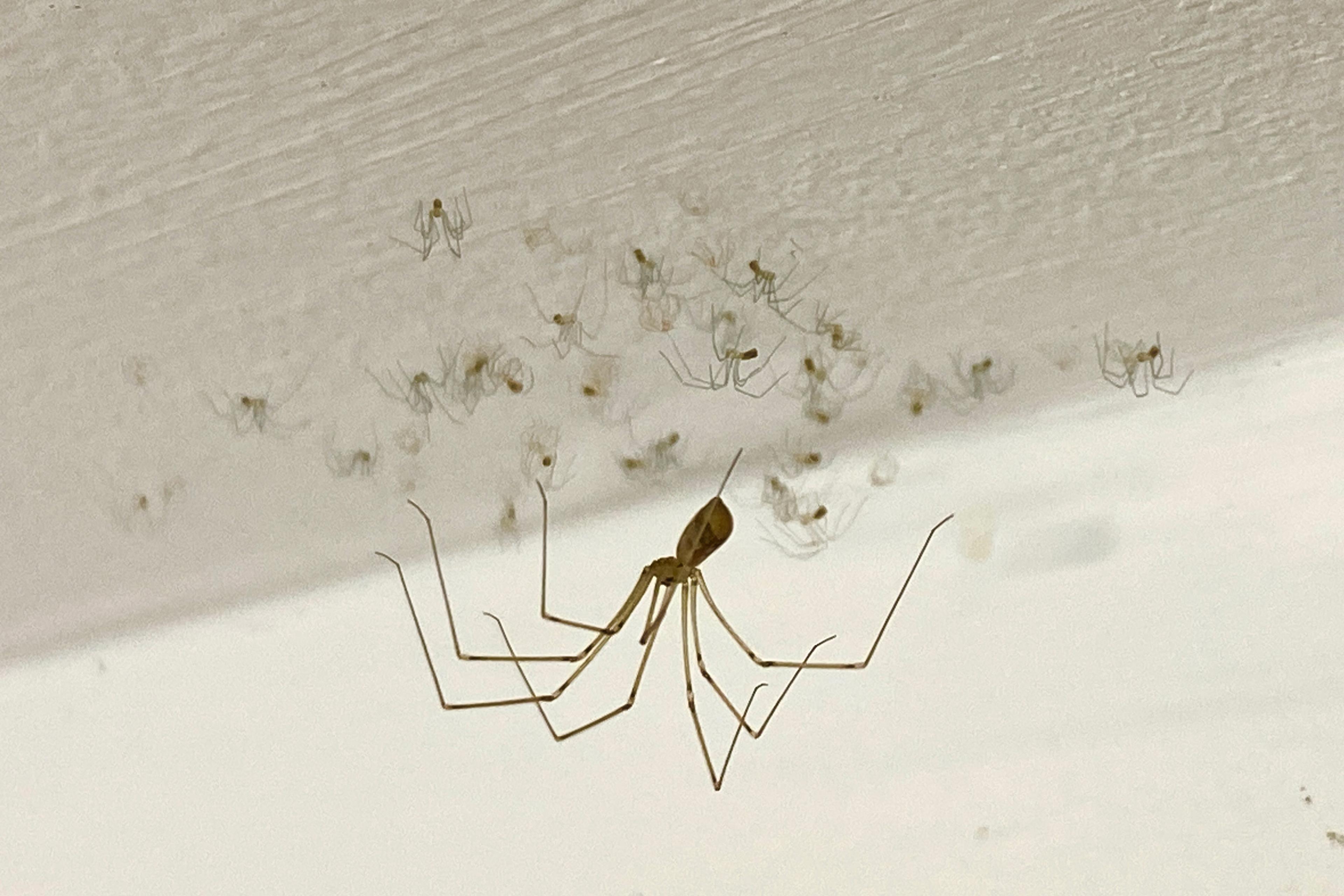

Does it really take brave madness to love us? With all our quirks and peculiarities, we can be challenging to live and work with, especially if we don’t even know the underlying cause and seemingly can do nothing to change, to make ourselves right. Yes, we have tried yoga and sunlight, going gluten-free and ‘just getting over it’, but it did not work, and it did not make us neurotypical. And for all that, we have probably felt less than lovable at some point. So it’s not surprising that many of us want to extend our own compassion toward those nonhuman creatures that society has labelled unwanted or disgusting somehow: spiders, reptiles, rats and also insects, of course. They are not wrong for being the way they are, you might just have to step out of your comfort zone and look a little closer to see their beauty. They all deserve protection, safety and a place to call home. So by opening our hearts to those who have too many legs or scales or fangs to be deemed acceptable, we symbolically care for those feral little animals within ourselves. With all our prickly, gooey, many-jointed parts, we are deserving of that very same acceptance. Like every critter on the planet, like every ant in a colony, we should be allowed to occupy and construct our own niche in the system.