Most college professors have had to deal with plagiarised papers from their students, and my experience is no exception. The problem has long been widespread. In one anonymous survey of tens of thousands of college students in the United States and Canada, more than a third admitted to plagiarism in some form – and this was before they had access to a near-perfect method (in ChatGPT) for submitting work that is not their own.

I recently spent several years as a dean at my university, where I oversaw the response to violations of academic integrity across the arts and science disciplines. In almost all cases of plagiarism, students gave the same defence: I didn’t mean to. They insisted it was the result of a mistake, sloppy note-taking, or misunderstanding the rules.

The accusation of plagiarism can feel formidable. Denying intent allows one to try to sidestep the accusation. ‘Perhaps I’m guilty in some technical sense, but I’m not dishonest!’ But does a lack of intent matter? Is there really a complete lack of intent? And what does this tell us about a writer’s moral character?

Let’s start with whether a lack of intent matters. A professor of history at Princeton recently defended himself against accusations of significant and serial plagiarism by giving the same kind of defence that students give: I didn’t mean to. Perhaps because politics was involved (the scholar who made the allegations was on the opposite political side to the history professor), the academic community mostly looked the other way. The professor subsequently shared that he had been cleared of misconduct. When the president of Harvard, prior to her resignation, recently faced a similar situation involving allegations of plagiarism, the university suggested that she was guilty only of ‘inadequate citation’ and ‘duplicative language without appropriate attribution’ and said that no evidence of ‘intentional deception or recklessness’ had been found.

Unfortunately, cases such as these could have consequences that reverberate across academia. Anyone who believes they should be exonerated on charges of plagiarism because they had no ill intent can marshal the examples of Ivy League academics in their defence.

To plagiarise simply means to represent another’s words or ideas as one’s own. It does not require ill intent. Definitions of plagiarism, especially in the context of higher education, typically either say nothing about intent, or explicitly state that plagiarism can be unintentional. Plagiarism does not require ‘an attempt to conceal an intellectual debt’ as was suggested in the Princeton case. Careless cutting and pasting, honest omission of a citation, and lazy paraphrasing (sometimes called ‘patchwriting’) are all instances of plagiarism. Of course, to say that intent is irrelevant to whether an act counts as plagiarism is not to say that it’s irrelevant to how plagiarism should be dealt with. Buying a paper on the internet is different from careless cutting and pasting; the latter does not merit suspension or the end of one’s career. But it is still plagiarism.

There is a common view in contemporary moral philosophy that holds that intention is irrelevant to an act’s permissibility. For example, giving someone a meal that poisons them would be wrong, even if there was no intention to cause harm. If you accept this view, it’s easy to see why plagiarism that is unintentional is still wrong. However, even if you reject this as a general view, as I do, and you allow that intention might be a key ingredient that makes some acts wrong, that does not mean that intention is key for every act of wrongdoing.

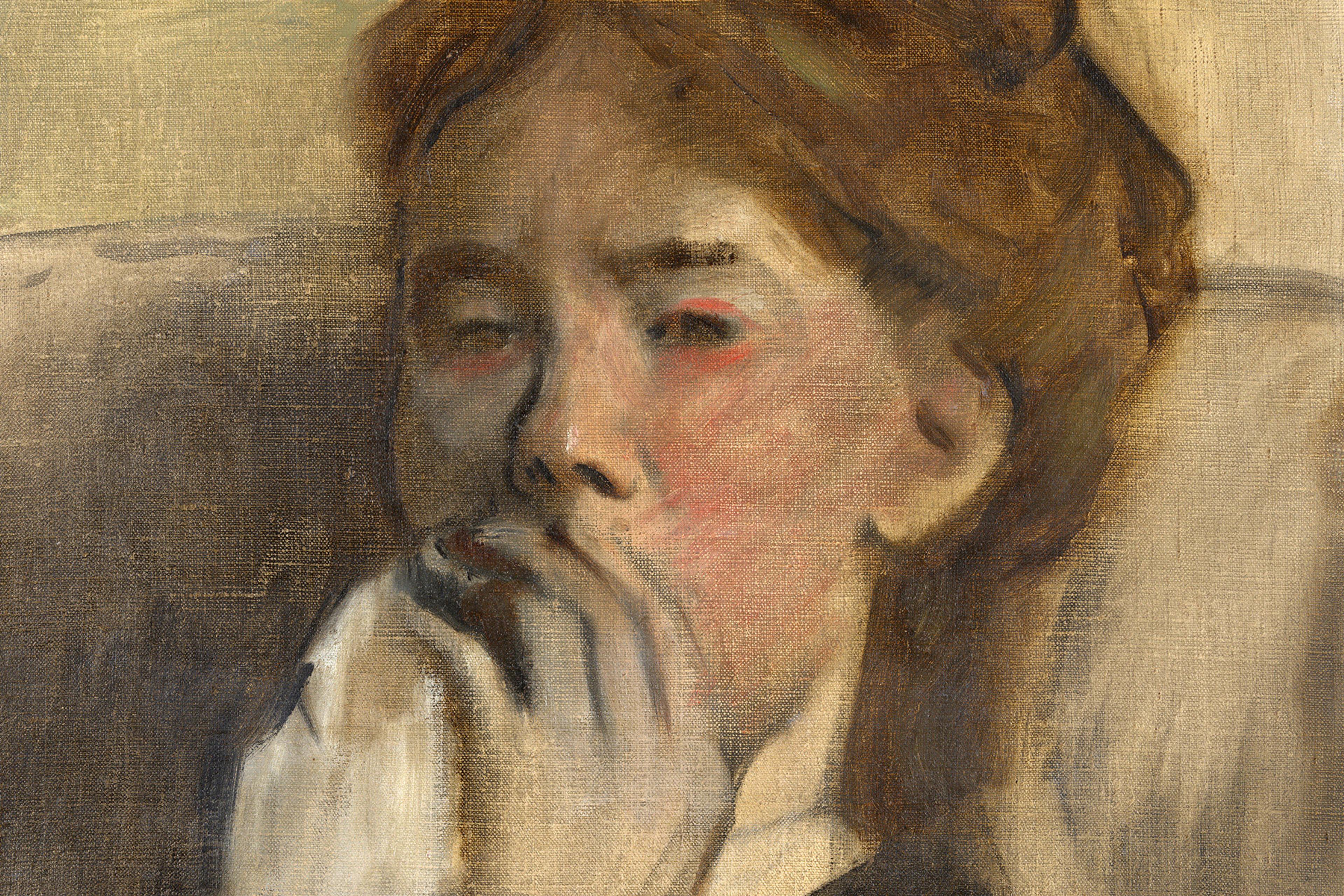

Speeding can have various costs even if it is unintentional and seems mundane

Most of us recognise the difference between actions where ill intent matters and where it does not. Being guilty of exceeding the speed limit has nothing to do with my intention. The law identifies such actions as ‘strict liability’ offences: speeding and selling alcohol to minors do not require any ill intent in order to be unlawful acts. These are distinguished legally from wrongdoing that requires ill intent (or mens rea). In order to commit theft, for example, one must intend to deprive someone of their property. Plagiarism is more like speeding than theft.

Just as speeding can have various costs even if it is unintentional and seems mundane, so too with plagiarism. The problem is not only that the person who was plagiarised did not receive credit. More importantly, the person who plagiarises likely fails to understand what it is that he is apparently trying to explain. This also creates problems for the reader’s understanding, and it violates the reader’s basic expectation that the author to whom information is attributed is the true source of that information.

Saying that plagiarism can be unintentional does not mean that all cases of plagiarism are perfectly clear cut. The line between good and bad paraphrasing, for example, is fuzzy, and citation practices across disciplines can be complicated and inconsistent. And there are other complexities. I have come to believe that when students tell me that they ‘didn’t mean to’ plagiarise, they are usually partly right and partly wrong. It might be best to think of their plagiarism as half-intentional.

Plagiarisers only rarely think to themselves: ‘Now I will represent someone else’s words or ideas as my own.’ They rarely think things like: ‘I hope I don’t get caught.’ This is the sense in which they’re right to say that they didn’t intend to plagiarise. However, at the same time, they do cut corners. They do a poor job of paraphrasing or they are sloppy with citations or quotation marks. These acts are intentional acts – the words on the page did not get there by accident. The whole series of decisions together constitute representing someone’s words or ideas as one’s own. This is the sense in which they are wrong to say they didn’t mean to plagiarise.

The speeding analogy is again instructive. When I break the speed limit, I rarely think of my actions in those terms, and I certainly don’t think: ‘Now I will break the law.’ For this reason, I might say to myself (or the police) that I didn’t mean to speed. Yet, it’s not as if I was unintentionally driving at the speed I was. I was not drugged, my car was not malfunctioning, and I was not trying to hit the brakes when my foot began to spasm. Instead, I took a series of intentional steps that amounted to speeding, even if this description at a more global level was the farthest thing from my mind.

Half-intentional plagiarism is probably the most common kind

Here is a common example of how plagiarism can occur in a half-intentional way. An individual copies a sentence from someone else into his notes without using quotation marks, telling himself (honestly) that he has no plans to use the sentence in his own essay. Some time later, he uses the sentence anyway, and perhaps he believes (honestly, but wrongly) that he had paraphrased the idea. There is no global intention to plagiarise, but it is also mistaken to call this plagiarism unintentional or accidental.

Plagiarism can, of course, be egregious, either by starting with a global intention to borrow work or ending up there over time. However, half-intentional plagiarism is probably the most common kind, including outside of educational contexts. In 2019, for example, the former New York Times editor Jill Abramson had a book published about truth in journalism and was accused of plagiarising several passages. She admitted to citation errors, but spun herself into circles in denying that it counted as plagiarism. ‘There was no purposeful attempt to not credit someone’s work,’ she insisted in an interview with CNN. Melania Trump, Neil Gorsuch, Joe Biden and, most recently, Rachel Reeves in the UK, for example, have all fallen prey to apparently half-intentional plagiarism. Unlike most cases in education, it is probably even less likely for famous people to commit fully intentional plagiarism given the public scrutiny they know they will face.

Being guilty or accused of plagiarism is a difficult thing to accept. It feels as if it’s a mark against one’s character. After all, plagiarism is usually treated as a matter of dishonesty or a failure of integrity. These character attributions do not fit well with our own conceptions of ourselves as good people. In a study published in 2013, participants were less likely to cheat in an activity if they were instructed not to ‘be a cheater’, compared with if they were instructed merely not to cheat. People don’t want to think of themselves as cheaters or plagiarisers.

In order to maintain a decent self-image, people tell themselves and others stories about the missing citations or quotation marks that neglect the series of intentional steps that got them there. Scholars who specialise in academic plagiarism say that almost all professional researchers who are investigated for plagiarism defend themselves by denying intent. The idea of ‘I didn’t mean to’ as a defence against plagiarism reflects, I think, a deep human tendency to want to hold on to a belief in our own innate goodness.

To care about critical thinking is to care about plagiarism

The truth of the matter is that very few of us are either honest or dishonest in a comprehensive sense. Our character is mixed. And a mixed character lends itself to mixed actions. Part of this picture is to rationalise and redescribe our actions, and generally focus on the good parts of ourselves and ignore the bad. Plagiarisers are usually not bad people – but that does not mean their actions and self-understandings bear no moral fault at all. To discourage plagiarism, it could be helpful to do away with the idea that plagiarism necessarily means your character is vicious or that you should be barred from your line of work. This change might encourage people who have plagiarised to be more honest about how they screwed up.

The minority of scholars who maintain that ‘accidental’ plagiarism isn’t really plagiarism or isn’t a matter of academic integrity conflate the commission of an act with the act’s appropriate consequences or with the plagiarist’s blameworthiness. Moreover, these scholars assume a false dichotomy, where cheating is always intentional and deserving of punishment, and textual errors like sloppy paraphrasing or missing citations are always unintentional – merely matters of honest confusion.

To care about critical thinking is to care about plagiarism. Learning to think means learning to write. The tasks of thinking and writing, appropriately pursued, require distinguishing words and ideas that you put on paper yourself from those that you get from somewhere else. When we write out our own ideas, we make an attempt to understand and impose order on a perplexing world. This is different from the also-valuable task of seeing how others do the same.

We have to care about half-intentional plagiarism because it helps us see why plagiarism matters at all. If we are not careful about the distinction between our own words and someone else’s, then we risk losing the significance of the distinction altogether.