Anyone who has ever spent time Googling their symptoms will know the attraction of online self-diagnosis, whether for mental or physical health. It can be a way to assuage your concerns, make sense of troubling experiences and, if necessary, act as a first step towards seeking help from a professional. However, on the video-sharing platform TikTok, mental health-related self-diagnosis has gone to another level. Here you’ll find videos of people declaring, and in some cases acting out or even revelling in, their mental health problems and self-diagnoses.

It’s hard not to be impressed by the bold rejection of stigma and the potential of psychoeducation in some videos, yet there are also troubling elements to the phenomenon. There is misinformation in some cases and, more distressingly, some desperate cries for help that could backfire and serve as behavioural instruction manuals to others. TikTok has acted to take down disturbing content and to regulate videos about eating disorders, self-harm and other topics. But while some content has become regulated, the sharing of personal narratives and experiences of mental health difficulties has continued to bloom.

Many users on the site have been frustrated by their encounters with mental health professionals. Some share moving stories of feeling misunderstood. A common theme is that they’ve described to professionals how they’ve masked their symptoms in the past, yet they say their accounts have been met with scepticism. Sometimes, the videos even manifest as outright hostility towards mental health professionals. In an example from 2021 with more than 50,000 likes to date, the user angrily affirms self-diagnosis and condemns professionals, as ‘not knowing shit about autism’.

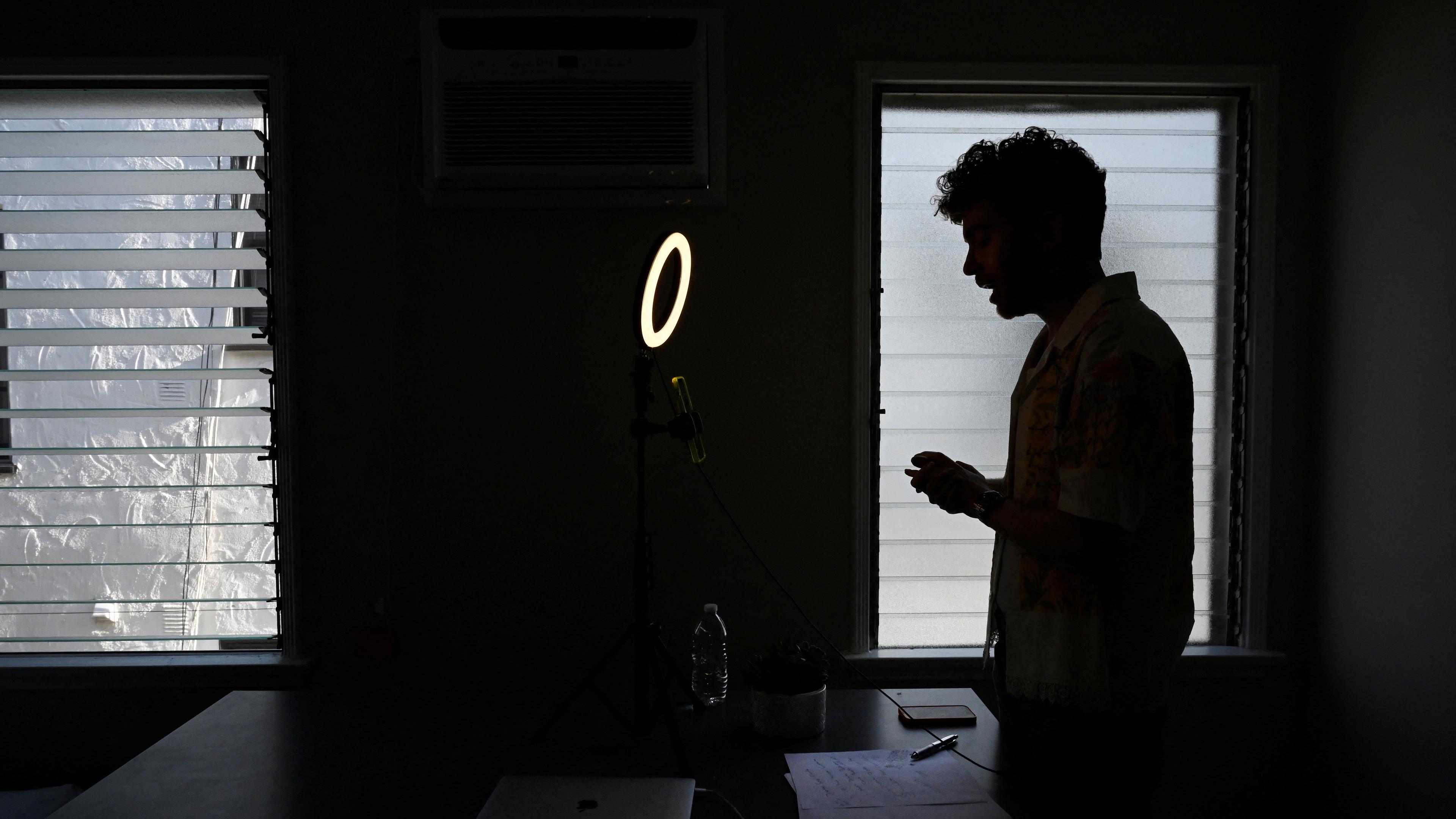

Understandably perhaps, many mental health professionals are alarmed by these developments and the platform has now become a scene of intense and sometimes acrimonious debate between people who self-diagnose and defend the right to do so, versus mental health professionals who see themselves as the only ones qualified to make diagnoses and who are critical of self-diagnosis. For example, in a video from 2022, the TikTok user – a psychotherapist practising in Utah – defends mental health professionals as experts and scathingly condemns self-diagnosis as misleading and mistaken.

Working in mental health ourselves, we’ve been watching these developments unfold. We see it as unfortunate that mental health professionals and people who self-diagnose are currently talking past each other. There is a missed opportunity for the two sides to learn from each other.

Our wish for mental health professionals on social media sites like TikTok is to soften the rhetoric. You are likely to be heard better if your message is not delivered with self-righteousness or even a subtle edge of certainty that you are right. Keep in mind that self-diagnosers on TikTok are suffering souls: their claim to have figured out what is wrong does not mean they have sought or received help to make their lives better.

Yes, mental health professionals can claim expertise about formal psychiatric diagnoses, including knowing the specific criteria for disorders. But let’s not pretend there aren’t serious concerns about diagnostic methods among mental health professionals themselves, including that diagnoses are insensitive to cultural values and differences in the expression of emotions; that professionals often disagree about the correct diagnosis for a given patient; and that the very notion of fixed categories of disorders might be a misconception (some experts believe all mental health exists along a spectrum, underpinned by key psychological processes such as moods and beliefs). Other approaches seek to view all diagnoses with more complexity and subtlety. For instance, the Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual (2nd ed, 2017) emphasises that, regardless of the diagnosis, personality style should be taken into account – consider how major depression will manifest differently depending on whether someone is naturally more withdrawn and slowed down, versus more jumpy and agitated.

Mental health professionals have a right to defend their expert perspective, which relies on research findings and clinical experience. But they will elicit a better response in presenting their perspective if they convey a sense of curiosity toward self-diagnosers and if they acknowledge, rather than suppress, the uncertainty about formal diagnosis that exists among experts. Why not use the increase in self-diagnosis videos as a chance to tune in to patients’ subjective experience of disorders and diagnostic constructs? Surely it’s better to be open to considering how patients’ perspectives can contribute to an improved understanding of mental health?

Although some self-diagnosers are resentful toward mental health professionals because of experiences they have had, others are less so, and are more invested in articulating their self-assessment than condemning formal diagnoses. In these cases, psychologists and psychiatrists might learn a lot from listening to how people describe their experiences. For instance, we came across an example of self-diagnosis on TikTok (and other forms of online media) that does not exist in the professional realm. We are not endorsing this construct as such; we’re arguing that it’s an example of how first-person accounts on TikTok and other online media can contribute to the study of mental health.

The proposed condition is known popularly as ‘AuDHD’: the co-occurrence of autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. One creator who identifies as AuDHD describes in a video from 2022 (with more than 50,000 likes to date) that throughout her life she felt as though she was ‘observing the human experience’, and only once she learned about autism, ADHD and their co-occurrence did she feel represented in ways that were both affirming and nuanced.

First-person accounts can serve as a valuable complement to formal empirical study

In a subsequent video she released shortly afterwards, the same user addresses criticisms from commentators that ‘everyone experiences those things’ which she’d said mark her out as neurodivergent, including various symptoms and ways of relating to other people. She differentiates neurodivergent people from neurotypicals through examples of noise sensitivity and problems with motivation. Many find noise annoying, she argues, but it doesn’t cause them panic or avoidance. Trouble with motivation may be common, she says, but neurotypicals are not immobilised, unable even to take a drink of water, and trapped in a cycle of self-hatred. She’s describing what clinicians would call ‘functional impairment’ – whereby symptoms interfere with daily functioning in a significant way.

First-person accounts like these can serve as a valuable complement to formal empirical study. For instance, supporting the anecdotal accounts of a link between autism and ADHD, research shows there is a high rate of people receiving a formal diagnosis of both autism spectrum disorder and ADHD. One recent meta-analysis – a study that combines data from previous studies – found that, among people with autism, around 40 per cent went on to receive a diagnosis of ADHD at some point. The fact that psychiatry’s diagnostic manual didn’t even allow for a combined diagnosis of ADHD and autism until 2013 shows how much the profession has to learn from people’s descriptions of their experiences.

The phenomenon of self-diagnosis on TikTok isn’t only a potentially valuable resource for mental health researchers and clinicians. For many people trying to find out if they have a mental disorder, a first step is to search around the internet and dip into social media sites. The immediate availability of information can be compelling, especially where there is a match between your symptoms and the symptoms reported by a self-diagnoser. You might find comfort and understanding with other self-diagnosers who seem to capture your experience in their descriptions. For many people, diagnosis-based identities can also offer a sense of community rooted in shared experience. Some self-diagnosis advocates on TikTok also argue that it’s a way to overcome sociodemographic barriers, such as being a person of colour, given the history of biased diagnosis and inaccessible treatment for minoritised groups.

For people using TikTok and other sites in this way, we’d urge you to keep an open mind: if you find someone describing a diagnosis that resonates with you, it might be an accurate diagnosis for you too, but it could be only partially accurate, or perhaps another disorder might be a better fit – it’s worth investigating thoroughly before forming any conclusions.

If after further investigation you still feel that you have the same diagnosis as someone posting on a social media site, we strongly recommend that you seek confirmation from a mental health professional. This will give you more confidence in the diagnosis. Yes, if you see a mental health professional, you deserve to feel that that person is listening with curiosity and attention. Don’t overgeneralise from a disappointing experience with one mental health professional. If you do not feel comfortable, try someone else.

Used sensibly, TikTok and similar platforms have much to offer the mental health community

If you are a teen or young adult, you ought to confide in your trusted friends and parents, if possible, to ask them if they have observed the symptoms that you believe apply to yourself. Remember that the people around you and who care about you might see you in ways that differ from how you see yourself. If you’re a parent and you’re concerned that your child is identifying with, and placing trust in, self-diagnosis from TikTok, you should avoid condemning self-diagnosis, and instead engage your children in conversation on being cautious about jumping to conclusions without vetting them fully. Anyone using social media as a diagnostic tool should also keep in mind that content creators do not know you at all and might have a vested interest in espousing their view; they are not able to assess whether you have a disorder or not. As we noted, diagnosis can be tricky, and it is best to regard it as it is meant to be – a snapshot of a person at a particular moment in time.

Used sensibly, TikTok and similar platforms have much to offer the mental health community. The pot-shots exchanged between self-diagnosers and mental health professionals on the site serve no one’s self-interest. On the other hand, both parties have something to gain in extending generosity to the other.

In this vein, consider this fantasy of what TikTok could offer: a video depicting a self-diagnoser interacting with a mental health professional, processing whether the patient has the disorder and, most importantly, concurring that the patient would benefit from therapy. Is this fantasy realistic?

We’ll share one more fascinating video example, available on You Tube, featuring a patient, Stephanie Foo – the author of the memoir What My Bones Know (2023) – who arrives at a session with her therapist, Jacob Ham, with a self-diagnosis of complex trauma, which she is trying to fathom. She and Ham agree to audio-tape their sessions, comment on them, and then share their comments back in the session. The therapist is not as concerned as Foo is about the diagnosis, and they sometimes disagree, but he helps her by building their relationship. In the video, they reflect on their work together, and they both agree that it was through her growing trust in Ham that Foo was able to make significant progress.

In the end, it is venturing to seek help that matters more than naming and having faith in a particular label or disorder, whether on TikTok or in the therapy room.