How do animals think? When we attempt to understand other species, we often forget to ask ourselves this question. We rarely consider the nuts and bolts of how animals perceive their worlds, or what their experience of life might be like. Instead, our approach is observational and human-centred: we interpret their behaviour through the lens of our own lives. Even the experts – the scientists who concern themselves with nonhuman animal cognition, such as animal behaviourists or behavioural ecologists – often fail to envisage how animals think. I am one of them.

For more than 20 years, I have been a researcher and lecturer in the field of behavioural ecology for wildlife management and conservation. My job involves acquiring knowledge about the motivations of other species and making predictions about their behaviour – how they move, hunt, reproduce, eat and sleep. In the backyards of UK homes, I studied how foxes, badgers and hedgehogs compete for the scraps people throw out, and discovered why some human dwellings are more desirable for certain animals. On the leafy floor of a South American cloud-forest, I caught rare lizards, which exist on only two mountains in the world, to find out how they were affected by human-led changes to their habitats. And in Africa, I threw minced meat to hyaenas and lions to track their movements using indigestible pellets that resurface in their faeces, revealing their territory boundaries and interactions with one another.

Through my work with these and other species, I’ve tried to understand how and why certain animals do what they do. But my understanding was never based on how animals think. When I interpreted ‘behaviour’ – an animal’s response to a stimulus – it was always from a human perspective. It involved posing questions, recording data, offering answers based on statistical probabilities and then making management or policy recommendations designed to improve the lives of other species or our interactions with them. But recently, I have begun to feel there is something missing in this approach: it seems phenomenally insufficient for making sense of or empathising with nonhumans. It cannot help us fully co-exist with them. How can I ever hope to properly understand the behaviour of other species if I don’t understand how they think? Increasingly, I want to understand what it is like, to paraphrase the writer and polymath Charles Foster, to ‘be a beast’.

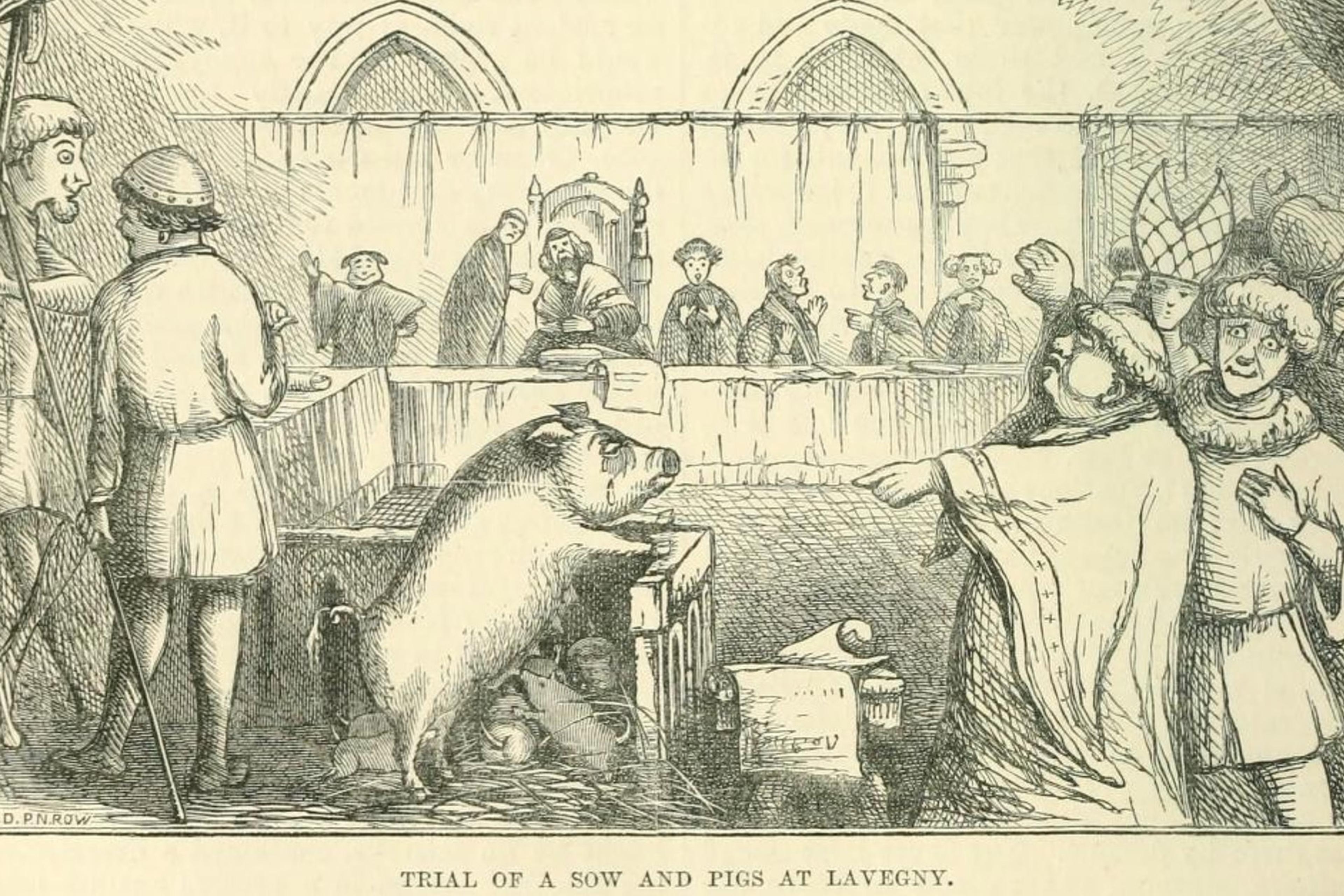

For hundreds of years, scholars from diverse fields, including philosophy, neuroscience, cognitive psychology and evolutionary biology, have tried to understand how other species experience the world. We have come a long way since the early 17th century when René Descartes claimed that animals were unthinking organic ‘machines’ without intelligence or reason. Today, it is clear that nonhuman organisms possess cognition, which the Oxford English Dictionary defines as ‘the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses’. Many species also experience affect – bodily feelings that precede emotions. Some even appear to express joy, love, despair or other emotions.

I remember wanting to think how the otter thought. I wanted to perceive its world

By 2012, scientific knowledge in the area had advanced such that the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness was published, its authors stating that ‘the weight of evidence indicates that humans are not unique in possessing the neurological substrates that generate consciousness.’ This does not mean that nonhumans have self-awareness or a theory of mind, as we do. But it does mean that humans may share some cognitive functions with other animals.

This suggests that I might be able to conceive what it is like to have the brain of my cat, Fred, or experience something like the thoughts of the otter I observed one day in western Scotland. As I watched it foraging on a seashore, I remember wanting to think how it thought. I wanted to perceive its world. This desire was partly whimsical, of course, but also a serious attempt to shapeshift across a taxonomic gulf for the purpose of deeper understanding. This is no mean feat for me. Like many academics, I am a word-thinker, and nonhuman animals, as far as we know, do not form complex thoughts using language in the way that most humans do. So how do we begin shapeshifting?

I started my search for answers by turning to literature. A recent wave of semi-scientific books about ‘the animal experience’ seems to have made this subject more popular. There is Being a Beast (2016) by the previously mentioned Charles Foster, with his wizardry of neuroscience, ecology and philosophy. There is also An Immense World (2022) by Ed Yong, who similarly looked for a ‘way in’ to animal perception by exploring the huge variety of sensory niches inhabited in nature. There are many others, including John Bradshaw’s Cat Sense (2013), which blends a more traditional description and explanation of cat ecology with an insightful exploration of cat cognition; the primatologist Frans de Waal’s Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? (2016); Peter Wohlleben’s The Inner Life of Animals (2017); and the neuroscientist Gregory Berns’s What It’s Like to Be a Dog (2017). These authors have reported elegantly on scientific studies to show that, if we ever hope to understand how other organisms perceive (and think), we need to know something about their worlds. But, invariably, the cues that other species use to navigate, communicate and find food are not the same as ours.

What is it like to be a bat? Thomas Nagel posed that question in 1974 in his seminal essay of the same name, which attempted to align the worlds of humans and other species from a philosophical standpoint. He suggested that human consciousness cannot be compared to the consciousness of bats. Most bat species (except the fruit bats) experience the world through ultrasonic sound. They live in a noisy and meaningful world of their own, through echolocation and social calls, which is mostly inaccessible to us. And there are many other parallel sensory worlds. Consider antennation, where insects (including ants) tap each other’s antennae, or scent communication where badgers, hyaenas, dogs and other mammals use faeces to ‘talk’ with one another.

Humans don’t normally perceive the world through ultrasound, electrical currents or symbolically meaningful smells. And, in my view, this makes it harder for us to empathise with nonhuman species. But those limitations don’t stop us from knowing something meaningful about how other animals think. Research on animal cognition has shown that most nonhuman species give and receive signals that direct their interactions with each other and with their external environment in a variety of ways. The neuronal circuits involved in these interactions have been documented in studies. Yet, none of this scientific research fully explains how it feels to be inside the mind of a badger, a swift, a praying mantis.

We humans use language to communicate, but we also use it to make sense of ourselves

Echoing Nagel’s conclusion about bats, Jacob Beck, a philosopher of mind, suggests that humans are unable to conceive of animal thought because other species think too differently from us – they think without needing language. Nonetheless, not all humans think predominantly in words, a fact that is becoming increasingly clear as we learn to understand and celebrate neurodivergence. Temple Grandin, a prominent animal behaviour scientist and livestock welfare researcher, who is also autistic, has presented a compelling case that certain species, such as ‘higher’ mammals, think in patterns or icons rather than words. Grandin herself thinks in pictures as well as words, so can presumably envisage this better than I.

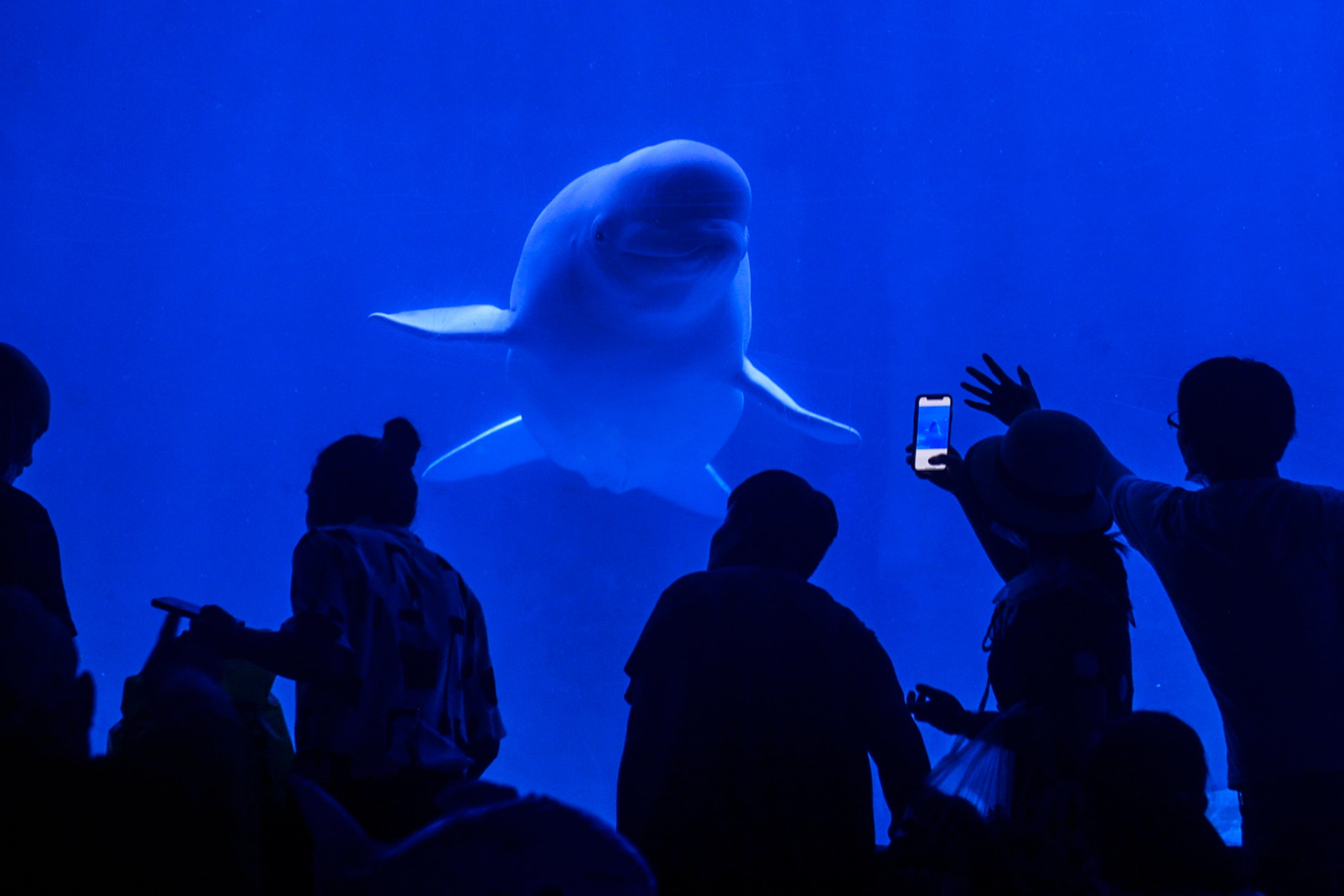

Rather than ‘language’ as we understand it, it is possible that other animals – particularly social ones like prairie dogs, dolphins or termites – think in the same unique ways they communicate with each other, through grunts, whistles, squeaks, touch, chemical signals or other signals. We do it too: aren’t human thoughts just echoes of our own spoken words? We humans use language to communicate, but we also use it to make sense of ourselves and our lives via internal narratives.

Indeed, our brain circuitry contains a particularly important set of structures from which these internal narratives arise. It is called the default mode network (DMN). This collection of brain regions becomes more active when we stop focusing on specific tasks or the outside world. It activates when we daydream, allow our minds to wander, reflect on the past, or imagine the future. It helps us make sense of ourselves as individuals, and it does this, for most of us, through words. We imagine hypothetical scenarios, plan, and contemplate our experiences by talking to ourselves in our minds. Linked brain structures broadly comparable to the DMN have been found in rats, mice and nonhuman primates, but there are fewer connections between the brain regions of these animals. In other words, even though they have the substrate for consciousness, and perhaps think in pictures or in a rudimentary language constructed from their particular mode of communication, their DMNs are relatively basic. For many species, it’s possible that the DMN is functionally nonexistent.

Perhaps then, we can mimic aspects of animal thought by quieting the DMN in our own minds. But how can we silence brain regions that activate almost unconsciously? Luckily, a suite of techniques exist – in the form of meditation and other mindfulness practices – that humans have used for centuries to calm the chattering of our minds.

Through meditation, I have caught the tendrils of this thought-consciousness without language. And I believe this experience may be similar – perhaps only for a few seconds – to the thinking of my feline friend Fred or that foraging otter I once watched on the Scottish coastline. Learning to focus on how we inhabit our human bodies in the present moment may be a way of glimpsing what it is like to experience the world as a badger, a swift or even a praying mantis.

But this is not easily achieved. Quieting the DMN requires practice. The long tradition of meditation teaches techniques for body awareness, mindfulness and focused affect, which can all temper the noise of the DMN. Mindfulness of breathing and mindfulness of body sensations are just two examples, but there are many others.

In ‘What Is It Like to Be a Bat?’, Nagel concluded that it is impossible to fully know the consciousness of other species, so we should leave their ‘thoughts’ well alone. I disagree. I say we keep trying – I say we keep finding new ways of becoming more empathic towards animals and understanding their needs better. Perhaps by learning to quieten the wordy chattering of our DMN, even for a brief moment, we can enter an unfamiliar sensory world and begin to experience what it is like to be another species.