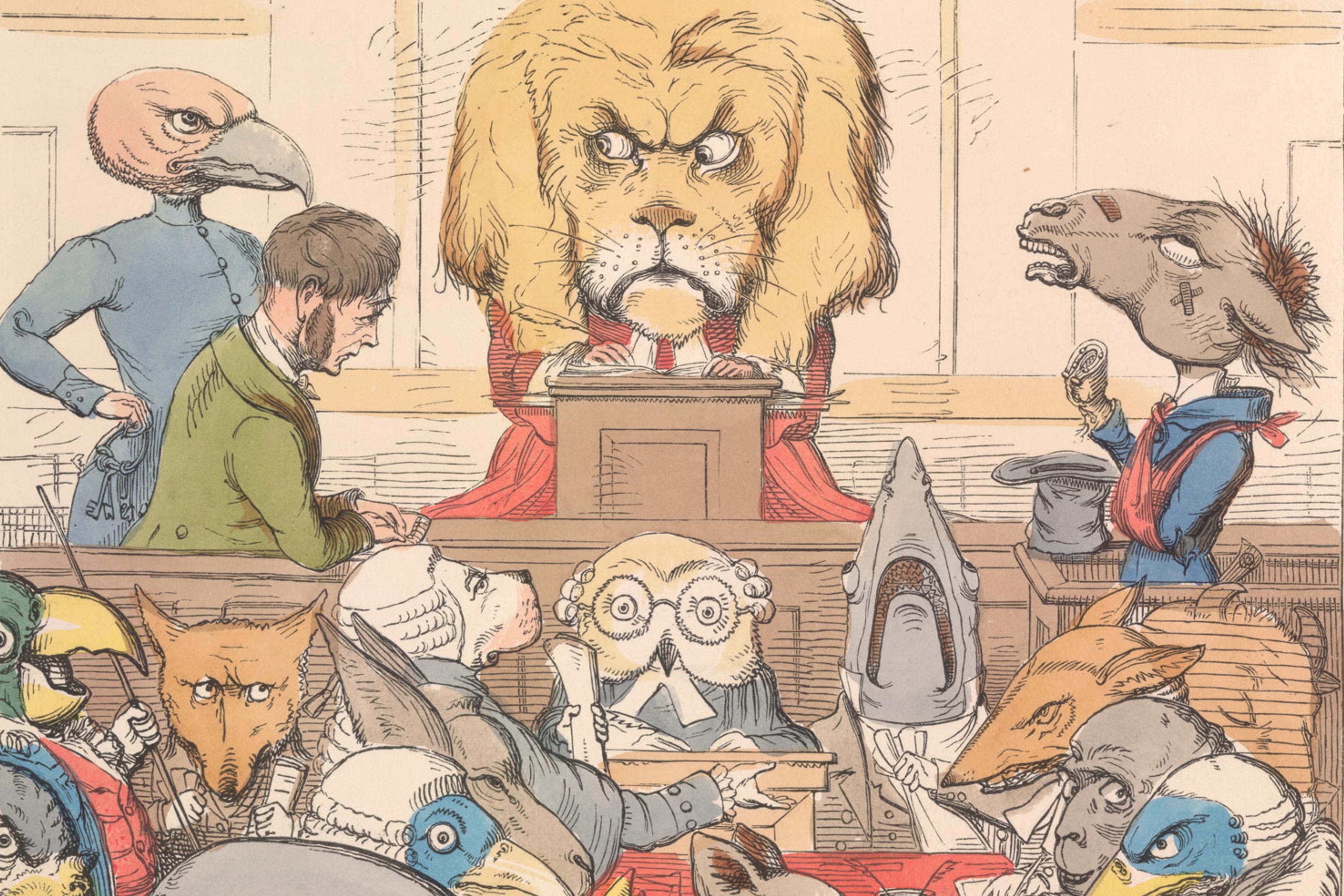

There were about seven birds of different colours that I used to see wobble around my neighbour’s urban chicken run. I frequently passed it on the sidewalk. Peering through the fence, I’d feel a bit of unease. I was a not-quite-vegetarian then: I’d given up some meat due to concerns about animal welfare, but still ate chicken. Yet here I was, charmed by these same feathered creatures.

What I felt was cognitive dissonance, a concept first described by the psychologist Leon Festinger in the 1950s. It’s the psychological discomfort someone experiences when what they know or believe is inconsistent with what they do. For instance, you might believe it’s wrong to lie but do it anyway, or know that a major corporation is harming people but still buy its stuff – and that might cause you some internal disharmony. Sometimes, people deal with that by rationalising their behaviour (eg, ‘everyone else does it’). Other times, they change.

A new paper by the researchers David Fechner and Sebastian Isbanner suggests that my increasing cognitive dissonance may have put me over the fence (so to speak) into vegetarianism. They compared several groups of people: those who ate meat and had no plans to change; those who were considering no longer eating meat; and those who had actually made the change. They found that cognitive dissonance (gauged by how uneasy, uncomfortable, etc one felt thinking about eating meat) was higher in the potential-vegetarian group than among the meat-eaters, and higher still among vegetarians.

Other factors differed too, such as how feasible a vegetarian diet seemed to them. But according to the researchers, the results suggest that cognitive dissonance helped to explain why some people who believed in vegetarianism’s benefits actually adopted it. When it comes to morally loaded behaviours, believing might not be enough. Our conflicts might have to stare us in the face.