When we think about romance, we often believe it exists outside the commercial landscape. From pop-song lyrics to cheesy catchphrases printed on mugs and cushions, this sentiment is expressed in tidy, well-known statements: ‘Money can’t buy you love’, ‘True love is priceless’, ‘The best things in life (love, companions, partnership) are free.’ Yet, just a quick glance at history proves to us that this isn’t really true. In fact, romance and commerce have long been intertwined.

Throughout history and across various cultures, the practice of older, more financially affluent individuals compensating younger, more attractive companions for their time and attention has been observed. If we stretch our gaze far back into history, for instance, to ancient Greece towards the end of the Archaic period (around 800-480 BCE), the custom of pederasty emerged. This was a socially recognised romantic relationship between an older male (erastes) and a younger male (eromenos), typically in his teens. Bringing the lens closer to modernity, in the early 20th century United States, the practice known as ‘treating’ emerged, where working-class women, often shop clerks in department stores, would offer companionship or sexual favours to male shoppers in exchange for meals, entertainment and gifts. Today, the same old story, whereby care and affection are commodities, is being retold, only with new language and social infrastructure to guide it.

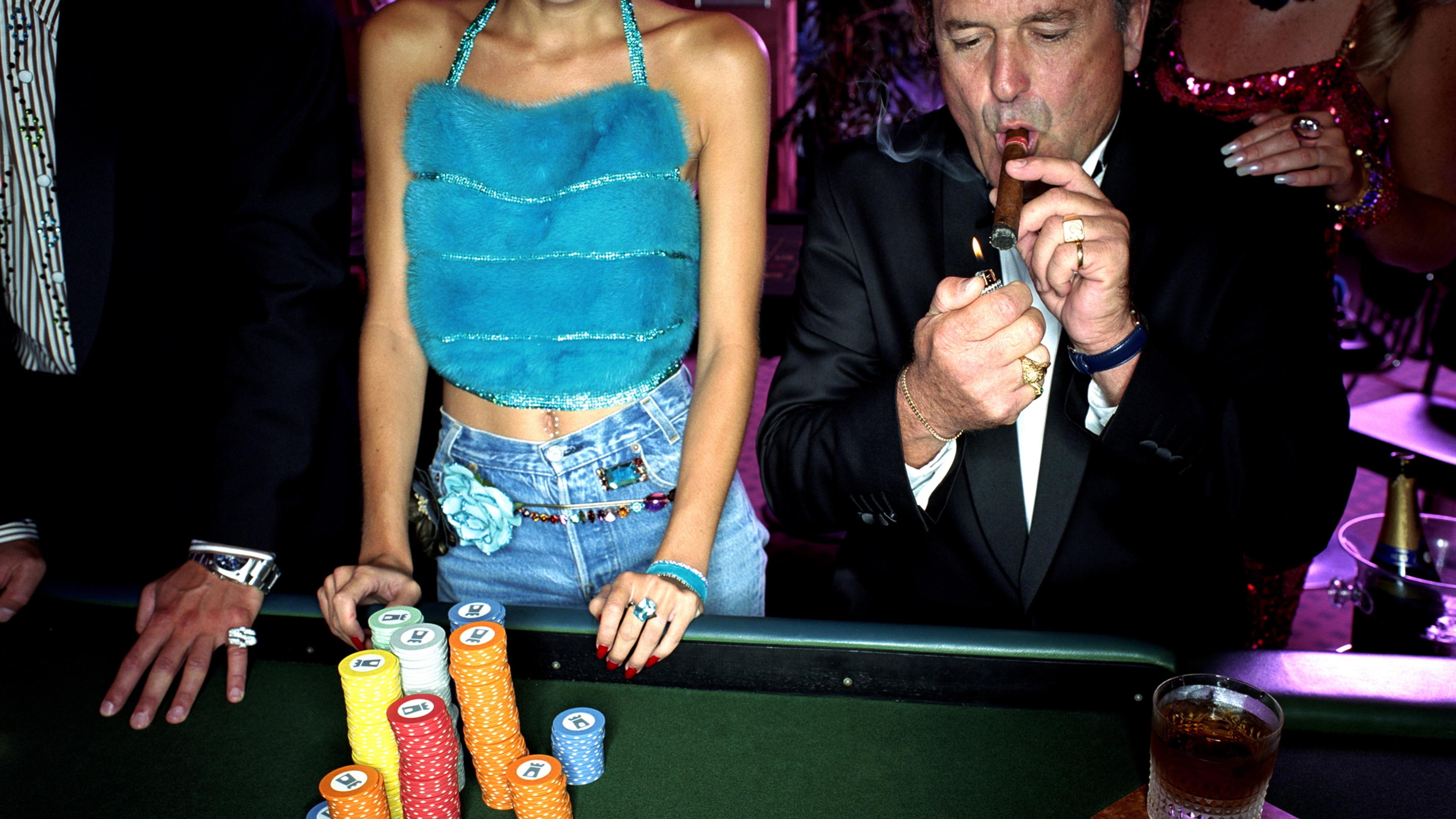

In 2006, the US entrepreneur Brandon Wade launched the dating platform SeekingArrangement (now officially known as Seeking.com, it shifted in 2022 to a regular dating site). Unlike other online dating sites, it catered to a niche user group: primarily older, affluent men seeking young, beautiful women. Here, the two can find a symbiotic relationship wherein the older man, referred to as the Sugar Daddy, can provide mentorship, rent coverage, network connections, and often weekly or monthly payment plans known as ‘allowances’. In exchange, the younger woman, referred to as the Sugar Baby, offers emotional, intellectual and often (but not always) sexual services. This phenomenon, informally known as ‘sugaring’, stands out as a unique aspect of modern life, straddling the line between what appears to be an authentic romantic relationship and a transactional arrangement.

Often, the two participants’ lives are entangled, spending nights at each other’s homes, going out for dinners or travelling together. To some degree, they build their lives around each other. Encapsulated within this relationship is a shared understanding that the flow of gifts and money will not stop. That this emotional, material and sexual economy is not a haphazard occurrence but an intrinsic agreement, essential for the survival of the dynamic. Together there is a collaborative blurring of what is bought, what is sold, what is performed labour, and what is an authentic action. The two lovers take on a dual role as both romantic partners and employer/employee.

What happens when one’s job is to perform as an authentic romantic partner?

From the Sugar Daddy’s perspective, this dynamic seems optimal – a sure way to secure consistent emotional and sensual investment in a cultural landscape riddled with loneliness. This is particularly poignant for many older men who feel engulfed by the demands of corporate capitalism, its knock-on effect of isolation, and the silo mentality that hegemonic masculinity produces. Conversely, sugaring is also beneficial because it provides financial compensation for emotional labour – the labour of validating others’ feelings, mediating their temper and alleviating their worries. All of which women have been historically overworked and undercompensated for.

At first glance, the commodification of romance seems straightforward. However, it becomes increasingly complex when we begin to examine the foundations of romance as a form of work. Specifically, what happens when one’s job is to perform as an authentic romantic partner – as the terms ‘perform’ and ‘authentic’ stand in direct polarity to one another. The amorphous nature of sugaring has the potential to leave many participants in a state of purgatory – straddling the authentic domain of dating, romance, and even love – as well as monetisation, income and labour. As a result, sugaring prompts a murky understanding of where one stands in relation to the other, when they are ‘clocked in or out’ of their job, what is contractually agreed upon, and what is monetarily ensured. All of which are questions any labourer within modernity deserves a clear answer to.

To answer these questions, I spent four months conducting semi-structured interviews with self-identifying Sugar Babies who either have had, or currently do have a relationship with a Sugar Daddy. While not all, many interviewees stated sugaring to be their primary source of income. It dictates their spending habits, rent agreements and savings accounts. However, since sugaring is also posed as a relationship, it can, like all romantic affairs, be terminated at a moment’s notice – similar to a breakup. This ending may take many forms, whether it be a lengthy, emotionally drawn-out breakup, a discussion over dinner, a quick call or text, or even a hasty ghosting. This leaves the Sugar Baby to reconcile both the loss of consistent income and the loss of a romantic partner – one whom they may have spent weeks, months or years getting to know.

With this volatility, there is also the issue of financial consistency. Lilah, a 22-year-old Sugar Baby from Canada mentioned during our Zoom call that often, in sugar relationships, conversations around payments take place early on. This allows both parties to understand what they stand to gain and provide before any emotional or sexual investment begins. However, this conversation is best understood as a loosely defined contract, relying on trust and mutual respect rather than written word or legal binding.

In contrast, within the mainstream workforce, workers are given clearly defined contracts outlining what is demanded and owed. Additionally, workers are granted annual reviews, prompting requests for raises to match inflation or reflect one’s growing commitment to the company. Sugaring, however, is far more informal. Renegotiation may feel inherently unromantic. Legal entitlement to compensation falls between the cracks. Lilah recalls certain moments when the monthly allowance would have been $200 less than what was originally agreed upon. Despite this breach of agreement, addressing the issue felt daunting, as it involved navigating a difficult conversation about trusting a romantic partner to uphold their word, as well as a worker’s right to fair compensation.

While the loosely defined nature of sugaring contracts can pose risks to financial stability, it also offers certain freedoms and autonomy. For example, Sugar Babies are free from the demands of traditional jobs that require them to show up at a desk every day, work a nine-to-five schedule, perform repetitive tasks, and spend hours on Zoom calls or in meetings. Jessa, a 25-year-old Sugar Baby from Australia, mentioned during our conversation that this freedom over her schedule was what initially attracted her to the practice. As someone with health concerns, she couldn’t always rely on mainstream jobs to provide the time off she needed for rest and recovery.

However, Jessa also noted that this freedom from conventional work demands often transforms into another form of restriction. Some Sugar Daddies expect extreme flexibility, requiring her to be available at a moment’s notice for trips or evening events. This reflects what scholars have termed the ‘autonomy paradox’, where individuals who appear to have significant freedom or independence in their personal or professional lives actually experience hidden forms of constraint or control.

Sugaring sheds light on corners of the world where romance and commerce explicitly blur together

In formal work settings, this is most commonly found among freelancers or ‘work from home’ employees who struggle to set boundaries, enforcing the end of the workday and the beginning of their personal time. Sugar Babies, too, are subjected to this, with open, sprawling days to explore the world, yet always with a red string tying them back to their partner. The evolution of technology only catalyses this – wifi, texting, FaceTime and social media platforms prompt Sugar Babies to be always available, always ‘on’, for their quasi-boss-meets-romantic partner. There are no out-of-office hours, no end of shift. If we reframe romance as a profession, it can quickly resemble a 24/7 occupation. From this, a type of ‘fictional freedom’ is born – barring Sugar Babies from the ability to set their own schedules, book time off, and step away from their duties.

Again and again, the phenomenon of sugaring raises the question of what happens when work and romance become inherently entangled – not in the sense of a whirlwind office romance, but in a more evolved form where a longstanding romantic relationship is itself a profession. Increasingly, social scripts have been written to distinguish the public sector from the private. In the public domain, we leave our homes or remote lives to engage in work, labour and finances, participating in acts of commodification, consumption and purchase. Connected to this we have come to believe that ‘on the other end of the spectrum’ is the private domain – comprising the home, family, and intimate relationships, which are acquired through abstract concepts like kindness, tenderness and intimacy, rather than bought or sold.

However, perhaps it’s time for us to reconsider how the two are continuously folding in on one another, bending to each other’s will and influencing their foundational nature. Sugaring does this for us. It sheds light on corners of the world where romance and commerce explicitly blur together, reminding us that themes such as love, labour, authenticity and compensation have always been, and continue to be, intricately interwoven – a far more slippery and arresting truth than we have previously been comfortable with.

Interviewees’ names have been changed to protect their privacy.