Many years ago, I asked a well-travelled friend which country had moved her most. ‘Cuba,’ she said. ‘People ask you to dance on the street.’ I grew up thousands of miles away, in a small city in China called Shaoyang, where my world felt tiny and uneventful. The most exciting thing was the fights: one kid might say: ‘Wait for me at the school gate.’ We’d all gather there too, anticipating a brawl, but even those often ended in a truce: ‘Come on, we’re all brothers.’

As a child, I had two nicknames: feifei or ‘fatty’, which referred to my body, and heipangzi or ‘dark fatty’, which referred to the colour of my skin. My best friend at school gave me the first name. I remember it being shameful to wear a bra. In the summer, the girls who did had a dry patch in the middle of their sweat stains and the boys would twang their bra straps from behind. I bought long T-shirts and extra-wide jeans to cover my chest and bum. Whether I was going to the toilet or in the playground, I’d clutch a jacket to my breasts, so people couldn’t see them.

My happiness came from small routines: like eating rice noodles. I’d carry them into school, stack my books really high, and hide behind them to eat. Sometimes, I’d treat myself to an ice-cream encased in chocolate, which cost 1 yuan. Then I turned 13 and had my first crush, on a boy who owned the stage during school performances. To get him to notice me, I put myself on a diet: one apple, one yogurt a day. My hair started falling out in clumps; I fainted in the school bathroom. I stopped dieting then, but kept using whitening masks to make my skin paler. When I bought foundation that was a shade lighter, my friends laughed at me.

Even in my 20s, that shame lingered – for not being pale enough, thin enough. Then, on a whim but probably because of the seed my friend planted all those years ago when she told me about Cuba, I went to Havana. I’d already visited many countries by that point, but Cuba was a shock. The first day, thinking it was dangerous, I walked around the youth hostel, then stood on the terrace to watch people. On the second day, I went for a walk in the afternoon, then in the evening, and made some local friends, one of whom ran a bicycle club. He wanted to show off and speak some English.

‘My girlfriend has a great body,’ he said. He told me the bigger the butt, the better. I didn’t believe him at first, but a lot of girls were like that on the street, their bodies like mine but in tight clothes that almost squeezed their flesh out. No one in Cuba, it soon occurred to me, insinuated I was fat or dark. Here, I was the mainstream.

Her confidence in her body defied every standard I’d grown up with

Later, I decided to sign up for a salsa lesson. Up until then, in my mind, dancing was what beautiful women did. A private class, I remember, cost $15. The building – which, from the outside looked small, almost hidden – opened into a gorgeous courtyard, its floor a mosaic of colourful patterned tiles. An old ceiling fan with wooden blades turned slowly overhead, creaking with each rotation.

Inside my teacher’s studio, a full-length mirror hung in the hall like a portal. She met me in a white lace dress that clung to her backside. Her long hair was pulled up into dreads, black-rimmed glasses framing her face. She was older – maybe in her 40s – and luminous. On her feet, she wore simple flat sandals, nothing remarkable, yet she moved with a rhythm so natural, so precise. Her confidence in her body defied every standard I’d grown up with.

She began with the basics – the paso básico – counting softly: ‘Uno, dos, tres. Cinco, seis, siete.’

Then came the ‘left turn’, then the corrections – ‘Don’t point your toes.’

I remember it had rained that day and the cobblestones outside were still slippery. The trickles of water between them were golden. When I was on the dance floor, someone nearby leaned in and told me: ‘Women revolve around men on the dance floor – but in life, men revolve around women.’

I’d been trying to shrink myself for years, physically and emotionally

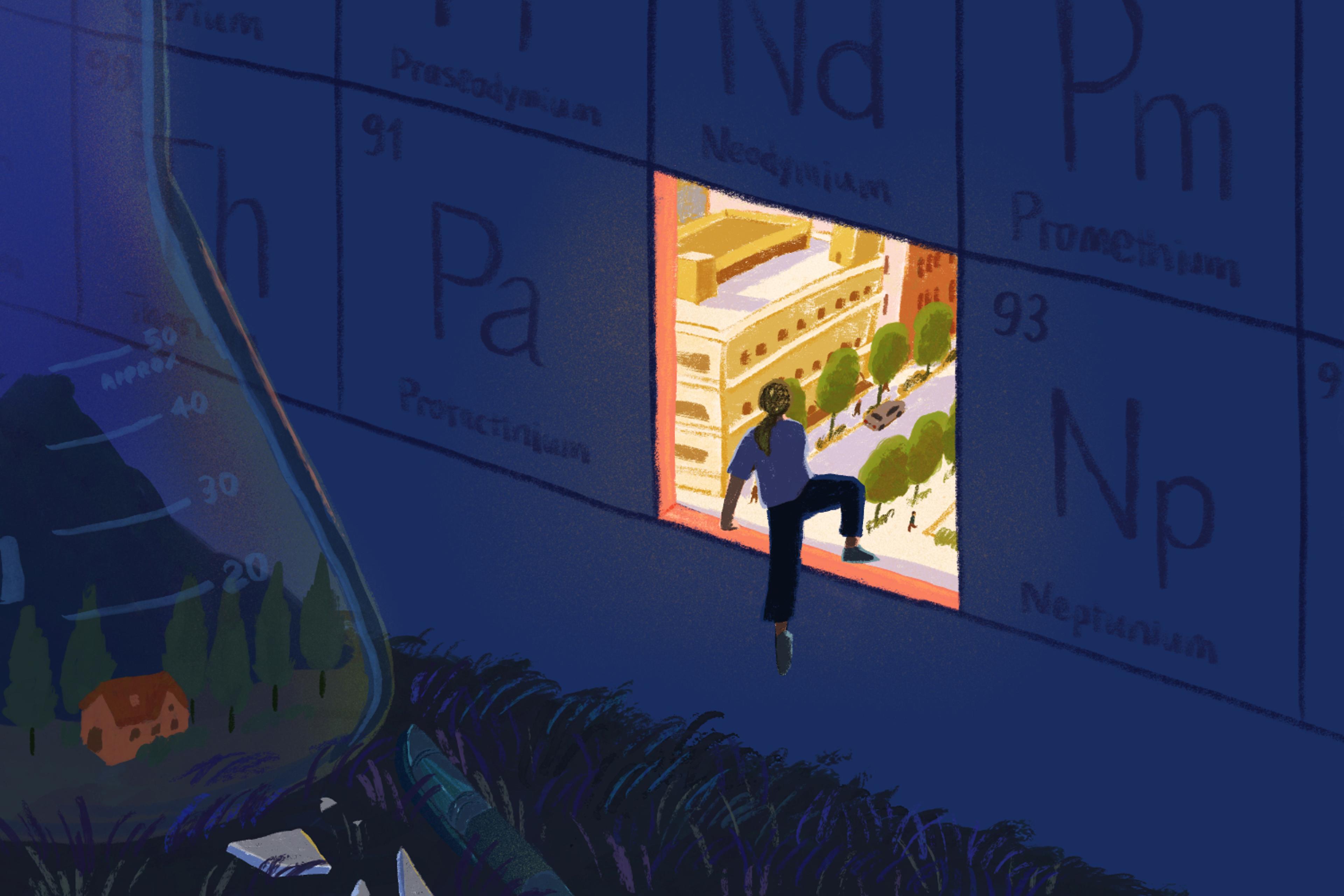

What I felt in Havana, I carried home with me and kept dancing. In Beijing, I found myself at Modernista, a bar that felt like it belonged to another city entirely: tucked down a narrow alleyway and easy to miss, with doors so discreet I nearly walked past them. I was wearing a strappy top, a new addition to my wardrobe since coming back from Cuba. In the past, I used to wear a puffer coat to clubs and just watch people’s bags.

I climbed the stairs slowly, passed through a modest lobby, and then came to a small balcony-like platform that overlooked a stage below – intimate, worn in, the kind of place I’d never expected would exist in a city like this. It surprised me, how much it reminded me of Havana, how a plain door could open up into a rich world. I could feel the past in both places.

The teacher opened the class with a short performance, dancing with one of the more advanced students to ‘Yo No Sé Mañana’, a sentimental salsa classic. I loved the melody so much, I started learning Spanish to understand the lyrics. You don’t know, I don’t know what tomorrow will bring, the song goes, if we’ll be together, if the world will end.

My teacher in Cuba had given me a taste – but it was a Cuban in Modernista who truly taught me how to dance. He was shy in person, but on the floor? He was magnetic. I realised I’d been trying to shrink myself for years, physically and emotionally. I was used to emotions being directed inward. I used to get lost in the quiet ache of Cantonese lyricists like Wyman Wong and Lin Xi who wrote of unspoken love and restraint. In Cuban music, all of the emotions were magnified and released. What you listen to is who you are. I still occasionally listen to those Hong Kong songs, but there’s no resonance. Now I dance to a salsa song that goes: ‘I like you. If you don’t like me, then I’ll move on.’