You who I don’t know I don’t know how to talk to you

—What is it like for you there?

– from ‘Sanctuary’ by Jean Valentine, in Door in the Mountain: New and Collected Poems, 1965-2003 (2004)

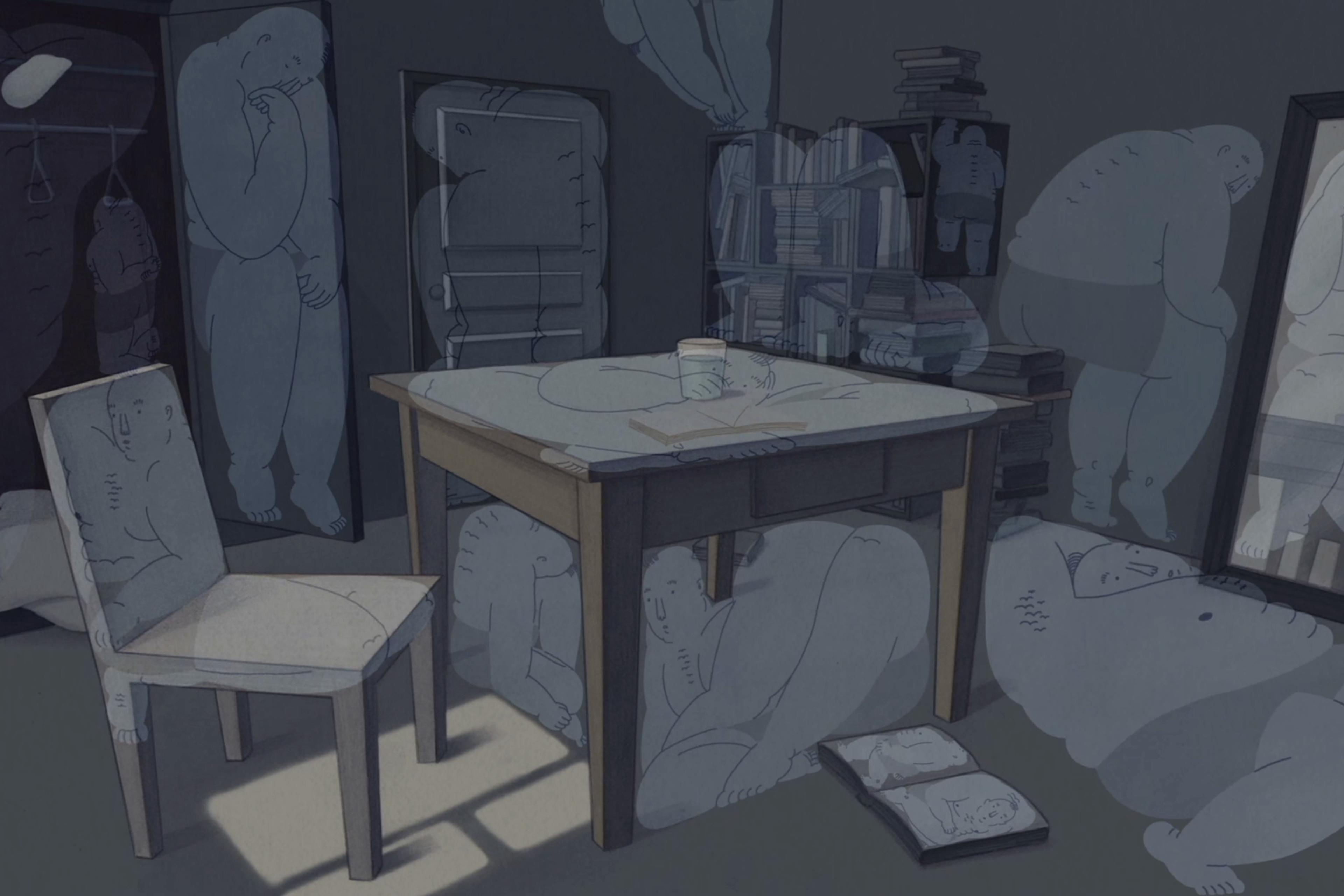

The opening lines of Valentine’s poem capture the disquiet terrain of the world as seen from the inside out, through the lens of an anxious psyche. Likewise, in Facing It, a young man of perhaps college age named Shaun grapples with the feeling of being trapped in the cage of his own mind, helpless to escape it. The viewer is given access to Shaun’s eyes and ears. His sensory perspective is dreamlike: imaginative, yet brushing up against a recognisable reality. But, as you might expect, it’s not a pleasant dream – his world is populated by characters with strange clay faces that sit atop human bodies, and their muffled voices echo incomprehensibly. As if submerged underwater, Shaun is out of his depth.

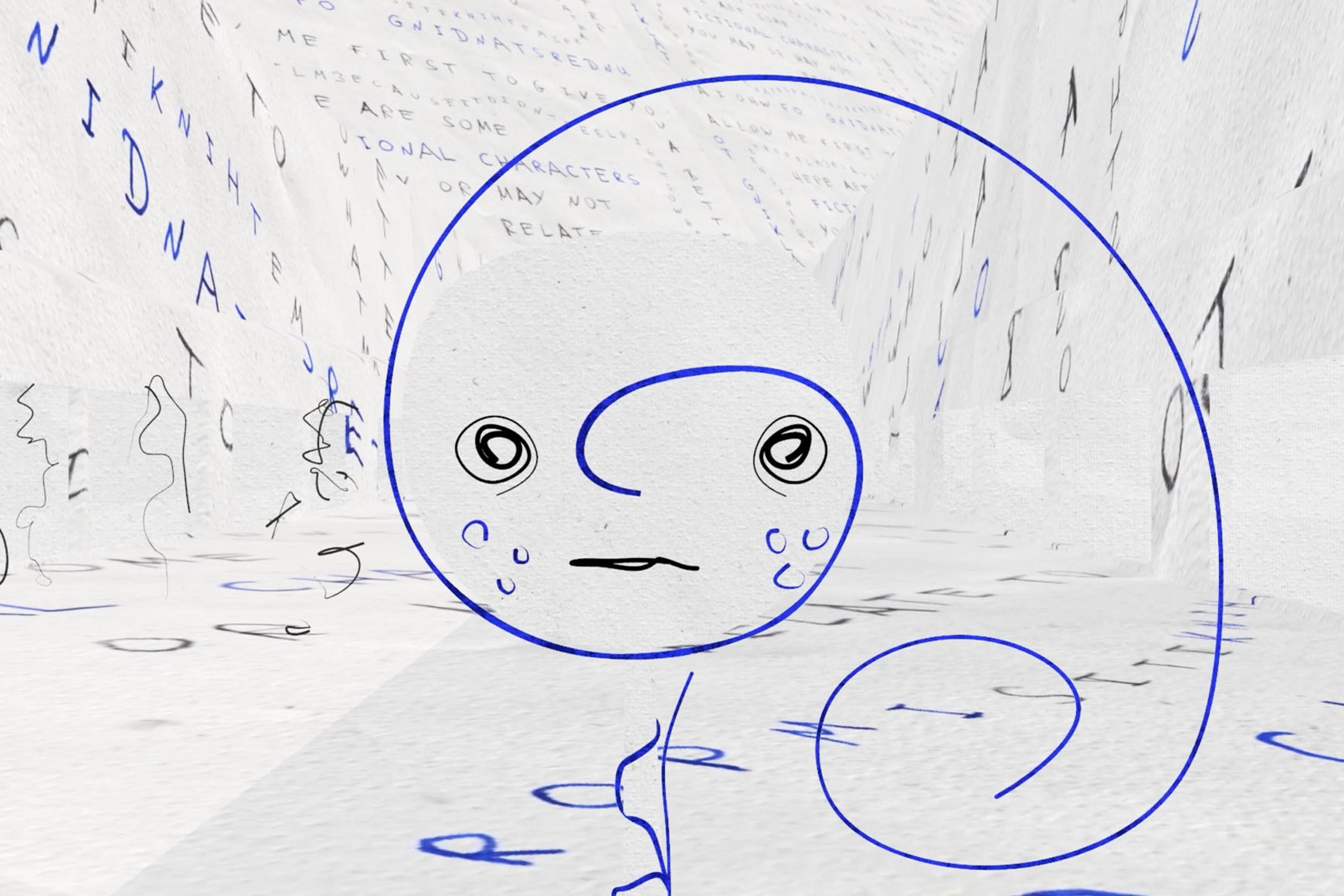

Following the trajectory of Shaun’s thoughts, the film floats back in time between the past and the present – the two indelibly interconnected. In the present, Shaun’s face is a vision of blue melancholy, melting and dripping as he makes panicked attempts to converse at a pub. We see these emotions at play, personified in the form of limbs that appear out of nowhere, stifling his efforts to socialise. Hands push and pull at his face, pluck out his eyes and cover his mouth mid-conversation; a foot kicks a glass out of his hand. Flashbacks reveal the ways in which he has become the embodiment of his past relationships; in particular, the troubled one with his parents.

To make Shaun’s raw emotions vivid and visceral, the UK filmmaker Sam Gainsborough deploys a mixed-media technique. Combining claymation, pixelation and live-action – a laborious and artful process – Gainsborough blends analogue and digital media. Through handmade indentations and growths on the clay faces, he inverts Shaun’s inner stress response, rendering it ever-present and tactile. And by integrating live-action human bodies and settings, he grounds Shaun’s experience in intertwined physical and emotional spaces, building an uneasy mood some viewers might find all too relatable.

By providing a window into Shaun’s internal world, Gainsborough highlights how our emotions and experiences are more complicated than even we can see, and tethered to our past, present and imagined future. The film reminds us that we can’t decode internal states by watching outward behaviours, since our exteriors are only the tip of a vast iceberg. As the speaker in Valentine’s poem ponders, even if we ‘imagine other solitudes’ and ‘listen for what it is like there’, it’s impossible to know what it is to be anyone else but us – even if, as Facing It seems to argue, it’s still worth trying.

Written by Olivia Hains