Have you heard this one before? An ultra-Orthodox Jew breaks the rules by going online, falls in love with stand-up comedy, and starts performing in bars and clubs to help manage his crippling social anxiety. With a killer deadpan delivery, David Finkelstein has developed a comedic sensibility that connects with audiences at open mics in New York City. But, despite growing more comfortable on stage and finding a second home in the comedy community, the experience is rife with challenges and compromises. Finkelstein is still devout and attempts to adhere to as many of his religion’s rules as possible, even as he operates in a cultural ‘grey area’ by performing. This means no physical contact with women, no vulgarity, and no shows on the Sabbath, which nixes the desirable slots on Friday and Saturday nights. And, most difficult of all, it means navigating between two very different worlds.

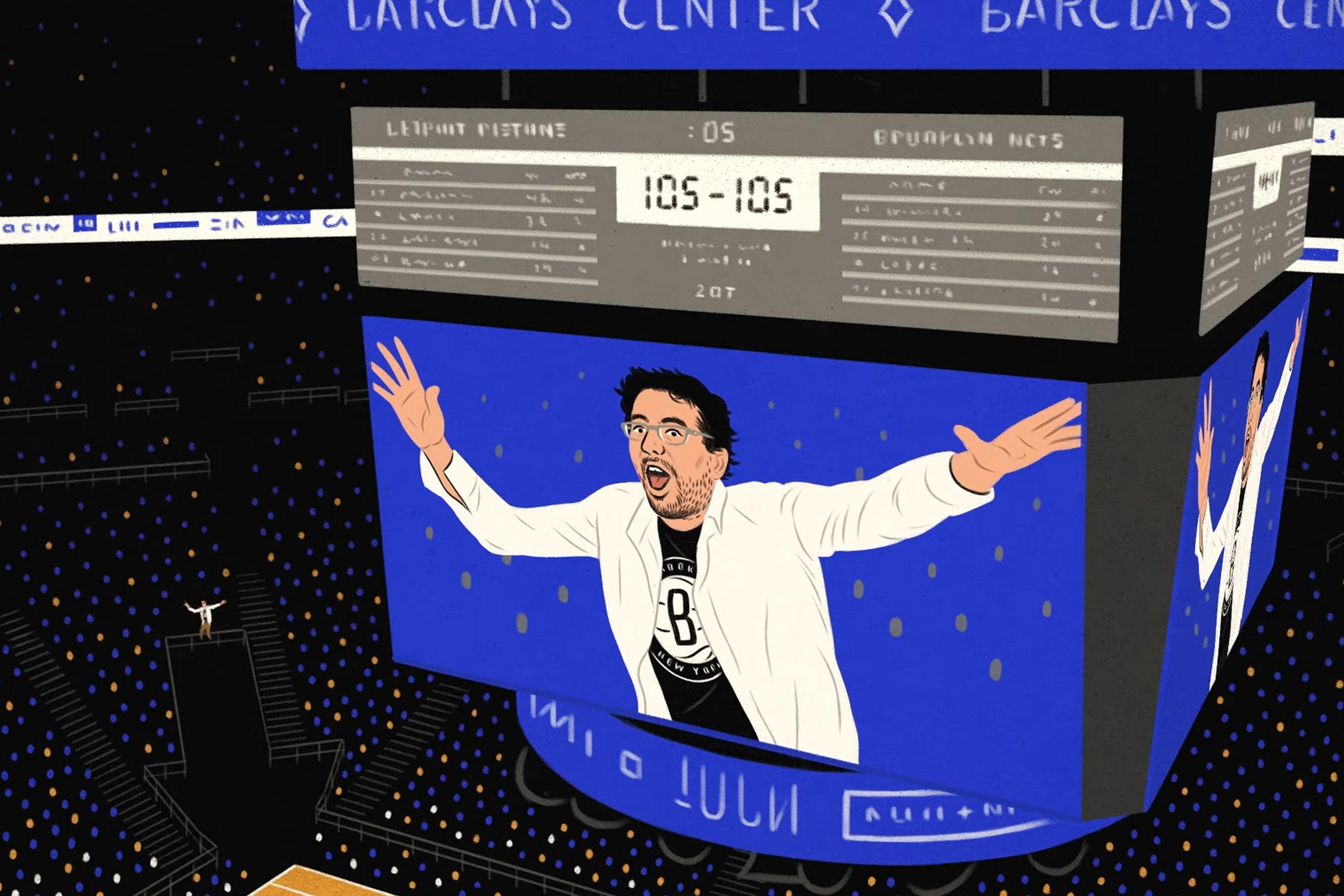

A Jew Walks Into a Bar (2017) follows Finkelstein as he tries to establish himself in the competitive New York stand-up scene while staying as true to himself, and his faith, as possible. The short is one-third of the US filmmaker Jonathan Miller’s feature-length documentary Standing Up (2018), which tracks three unlikely stand-ups as they pursue comedy. Miller captures Finkelstein almost exclusively in the comedy scene – a constraint that’s likely due in part to the difficulties of filming inside the Jewish Orthodox community. But this framing gives the portrait a sharp focus on Finkelstein’s unlikely foray into, and complex existence in, the world of comedy and comedians.

His nights in the bar-centric, often profane stand-up circuit brim with the kind of endearing fish-out-of-water humour that fills his sets. But, in his interactions with a diverse cast of comedy characters, Finkelstein embarks on a complicated path of self-discovery. Over drinks with comedy friends, he discusses how mining a laugh from his Orthodox clothes feels cheap and unfulfilling. Later, in an attempt to ‘mainstream’ his act, he trades his brimmed hat, white shirt and black trousers for a kippah, sweater and jeans. In another scene, he meets an outgoing female comedian. When the ever-neurotic Finkelstein tells her he can’t shake her hand, she presses her body up against his for a laugh. It’s a charming moment – he responds with a rollicking, good-natured laugh – but it also distills his feelings of belonging and difference into a single moment.

In religion, Finkelstein finds both a deep spiritual resonance and comfort that he’s not willing to abandon for comedy. And in comedy, he finds an outlet for his anxiety and the kind of emotional openness that his conservative community lacks. With the eminently likeable and compelling Finkelstein at his film’s core, Miller’s documentary is affable yet honest about the incompatibilities between these two worlds – a tension that never truly resolves. But even if the film captures Finkelstein’s final performances, his time on stage will still have been worthwhile, having helped to give him a new perspective on his anxiety, and audiences a chance to catch him in a rich starring role.

Written by Adam D’Arpino