‘I transform hate into love.’

– Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010), interviewed in 1989

Maman – are you this spider with her cage of eight legs? Your stilettos rear above me. Were you always this 30-foot ogress plunging me in shadow, even when I thought I’d escaped? Fear was a woman running on eight stilettos. You were a tree running on its roots, having no soil to anchor in. And here you are again, on the bank of the Thames, peering into the river with your many eyes, asking the water for answers, as if it’s your last moult floating between the streets of London. Lonely matriarch, listening to the water song with its wave slaps. Woman made of braided steel, monster I call Maman.

How many years has it taken for me to crane my neck to your abdomen? Dare I look up now? I throw my head back to see your 17 marble eggs. My teenage self petrified in your mesh sac. I remember that girl in her room, her mother a spider under the bed. Calling her to help her mend the web. Let me praise you – even an arachnid daughter must be grateful to be on earth. Let me praise your weaver skills, your perseverance, your reparation. From you I learnt my art and persistence. I weave. I un-weave. I reweave. I mend each torn hour. I sit in my lair until the work is done, and even when critics rip my orbs, saying they are too private, I repair them.

Why am I so scared of you, Maman? Louise Bourgeois says she transforms hate to love. I too make this claim. For you, I have gone into the Amazon rainforest at night with my blacklight torch. I have shone it onto a scorpion, her stinger poised as she pretended to be bark, waiting for me to grab the tree to steady myself. She was an ultraviolet goddess. I have shone my torch at the hole under a buttress root, at a burrow entrance. I have teased it with a stick. You darted out as a bird-eating spider, bigger than my hand. I have stood there like an infant frightened of her mother’s hand, the sting of her fingers. Why am I still frightened of your hands when you died long ago?

I say the word ‘maman’ and have to hide from myself. Am I inside your womb? Let me tell you how I deal with that terror. I have remade your womb, re-woven it with my spinnerets. I thank Bourgeois for her mantras, her life’s tapestries. Like her, ‘I do, I undo and I redo,’ ‘I want to recreate, recreate the past.’ She said:

My mother would sit out in the sun and repair a tapestry or petit point … This sense of reparation is very deep within me.

Oh, I have tried to write the hatred. How I hate you, my mother! I have been an arachnophobe all my life. Then at last, I produced a different thread like a reverse umbilicus – un-birthing and rebirthing my labyrinth.

Maman – I want to tell you how I changed you from a hummingbird-devouring tarantula into a flower. I worked my spinnerets into a frenzy, my eight eyes tranced your transformation. You became a giant ghost-white waterlily. I gave you a name, tied a new nametag around your wrist – Victoria amazonica. At first, you appeared as a baby, freshly washed by antipsychotics, you floated on a giant leaf in a backwater of the Amazon. The surface of the leaf was silken, but I knew that thorns underlay the raft, so many thorns, on every stem and rib. So, there you were, shining in moonlight in your basket of thorns, a caiman basking beside you, a hungry jaguar on the bank.

How quickly you morphed into a woman with too many legs. How eagerly I changed those legs to petals around your sex. We listened together to the predawn chorus of your flowering. The pale-winged trumpeters sang first. Their song was as sad as you, a low, drawn-out electric hum that contained every hurt you’d suffered, each pain had its quaver and echo as it foraged on the forest floor. I thought aliens had landed but, no, it was just my mother talking to the trees, begging them to listen to her story. Then the howler monkeys ballooned their voice-boxes and out came the howls of your childhood. Soon, beetles landed on your corolla, burrowed into your floral chamber. I knew to call each one Papa. You had no hands to push them away. Your white petal-legs turned blood-red.

And this is how I was made.

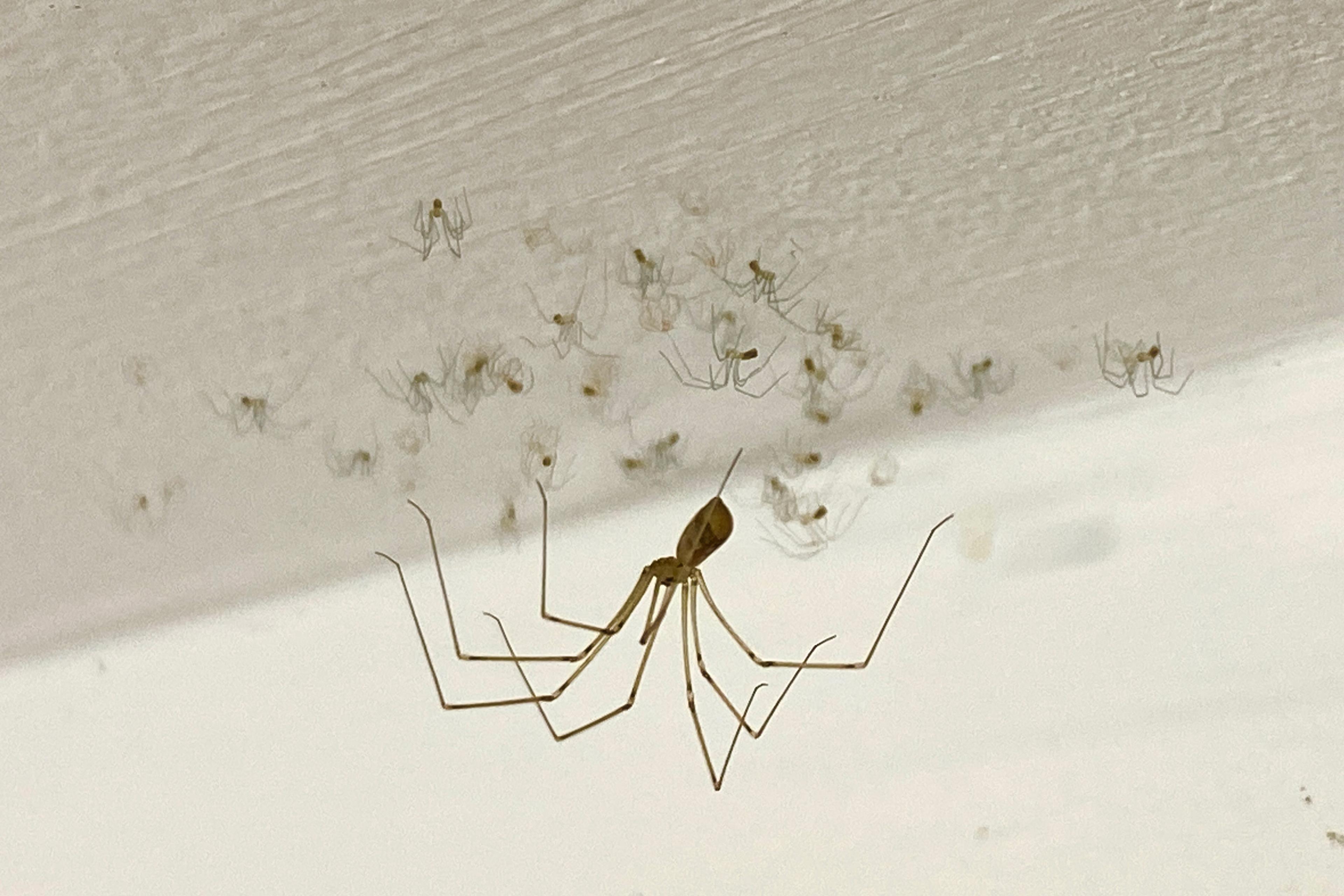

So, here I am, inside you, pollinated. The Amazon rainforest wove itself around me, tighter and tighter. I wove, I un-wove, I re-wove. I made a book of webs, called it Mama Amazonica. Each page was a nest of spiderlings that formed into words. Each page fluoresced into unknown species. Our deepest hurts grew into emergent giants – those ironwoods and kapoks, their buttress roots are the walls of our homes. Just as I once lived inside your body.

Your psychiatric ward was there too, its night monkeys and spider monkeys. Its rivers of sleeping night hawks, their eyelids heavy as I floated past them. Its catfish and spectacled caimans. Its king vultures and black hawks. The juvenile harpy eagle watched us from a lower branch of the web, an armadillo trapped in his claws. The giant river otters, those river wolves, uttered their wavering screams that signalled we were not safe in the Day Room, that the whole Amazon rainforest was a Sleep Room. Nurses came with their trolleys of poison dart frogs, and you gulped down your medicine.

‘I transform hate into love,’ Bourgeois said. What a dewy cobweb shines around her spider. The Thames also shines, despite the silt and suicides. I stand outside Tate Modern, art’s cathedral. It once was a power station that produced electricity. Now it’s home to works of love. I’ll spend years exploring its galleries, looking at the manifestations of love, made from hatred, fear and war, from every experience. Even madness.

‘My best friend was my mother,’ Bourgeois said in 1995, ‘and she was deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat, and as useful as an araignée.’ I compare you to her, Mother. You were not soothing, not patient, not reasonable. You were clever, but your mind wove itself straitjackets. I ask Bourgeois why she was frightened of her mother, since she seemed to adore her. She answers: ‘I shall never tire of representing her … My reasons belong exclusively to me. The treatment of Fear.’ I try to imagine her feeling of betrayal, when her mother let the au pair, who became her father’s mistress, remain in their home for 10 years.

What do you think about that ménage, Maman, I ask. You shrug. You show me a part of the forest no one has seen before. Where a doe is giving birth and a jaguar is eating the fawn as it emerges. Write about that! you say. I say that I love deer and jaguars. That there is beauty in the cruelty. You tell me there are 17 marble eggs that you must crack so that the spiderlings can live. This scene is only the first. Then you tell me how I was conceived, that my father was a beetle I should have crushed with my shoe. You crack open the third egg and out comes the story of my birth.

You are drunk when you tell me how you were in labour for two days and nights. That in the end they cut you open and placed me in an incubator while they packed ice around you to control your fever. We are on a ferry as you say this. I can see us now, in the bar, the other passengers hushed because you’re saying too loudly that you shouldn’t have had children. ‘The treatment of Fear,’ Bourgeois repeats. I am standing inside her 30-foot-high spider as she says it, and a rescue boat speeds past on the Thames, making the river thresh against the bank, and her Maman sway slightly in the draught.

I ask the wind if it wants to blow us away, like the critics that disapproved of me writing about my mother, her madness and rape. But she holds firm, this arachnid. She insists that ‘I transform hate into love.’ And I’m smiling, even though I’m inside the beast and am an arachnophobe. Because I’m thinking, what a miraculous thing art is, if it can change hate to love. I’m thinking how momentous mother-love is. How central it is to our survival on this mother of a planet. Surely, a mother’s love – or its lack – is a universal force for good or harm? Surely this intimate family psychodrama is as important as spiders are to the living web of life?

I open my book of love that bears your new name, Maman. I open my collection of poems, Mama Amazonica (2017), where your wounds and your beauty are stored. It’s true that I still hate and fear you. But in this book I love you. I poured my compassion into its pages. I thank Bourgeois for her example. I leave Maman and go into the Turbine Hall, into the great engine of transformative power, grateful that there is art.