People across time and place have considered it both possible and valuable to influence sex with food and drugs. Until the advent of modern vaccines, no medical product had been more widely traded throughout world history than aphrodisiacs (the herbal or animal extracts purported to arouse sexual desire, stimulate genitalia or enhance erotic pleasure). References to aphrodisiacs are found in the medical sources of ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome, of premodern China, India and the Middle East, and in traditional pharmacies of several African and South American cultures.

One might expect that, due to their close relation to sex and intimacy, religious authorities would have long suppressed aphrodisiacs, but in fact this is not the case. Aphrodisiacs were systematised as a class of substance in elaborate detail by the apothecaries of the Islamic, Judaic and Christian worlds in the medieval and early modern era, for instance. They were broadly accommodated within the worldviews of the monotheistic religions.

Yet, by the middle of the 19th century, modern scientific biomedicine had come to discredit the very notion of aphrodisiacs, developing the view that such substances were at best wishful thinking, at worst the epitome of quackery. Recent pharmacological research hasn’t shown much interest in the vast knowledge banks of aphrodisiac medical traditions across world history, and most of the traditional substances purported to influence sex have never been subjected to modern scientific investigation.

The rise of sex-steroid hormone endocrinology during the interwar period, with its promises of libidinous rejuvenation, came close to proposing something like a prosexual pharmacy again, but shied away from explicit claims about hormones as sexual remedies. The new prosexuals of the late 20th and early 21st century, such as sildenafil (sold under the brand name Viagra, among others) and flibanserin (brand name Addyi), renewed the promise of modern medicine to stimulate failing erections and missing orgasms. But this was very different from the aphrodisiacs of old that were prescribed in numerous human cultures throughout history, and often used as much for other health purposes, of which sexual stimulation was merely one. They were both more holistic and less pathologising than modern prosexual pharmacy.

Whence came the premodern art of aphrodisiac pharmacy? And how did modern medicine come to reject it so comprehensively?

The notion of an entire class of medical substances thought to influence sexual desire and pleasure, though referencing the name of the ancient Greek goddess of love Aphrodite, wasn’t actually found in ancient Greece. In fact, the development in early modern Christian Europe of a distinct category of medical products defined by their effect on sex appears to have been heavily influenced by the Tunisian Arab Christian scholar named Constantine the African (c1020-99), who translated several of the ancient Greek works of Galen and Hippocrates from Arabic sources into Latin, and who wrote a Latin work on sexual medicine, De Coitu (‘On Coitus’), which described a long list of foods and medicines derived from medieval Arabic, Persian and Hebrew traditions that were thought to stimulate sexual desire and pleasure.

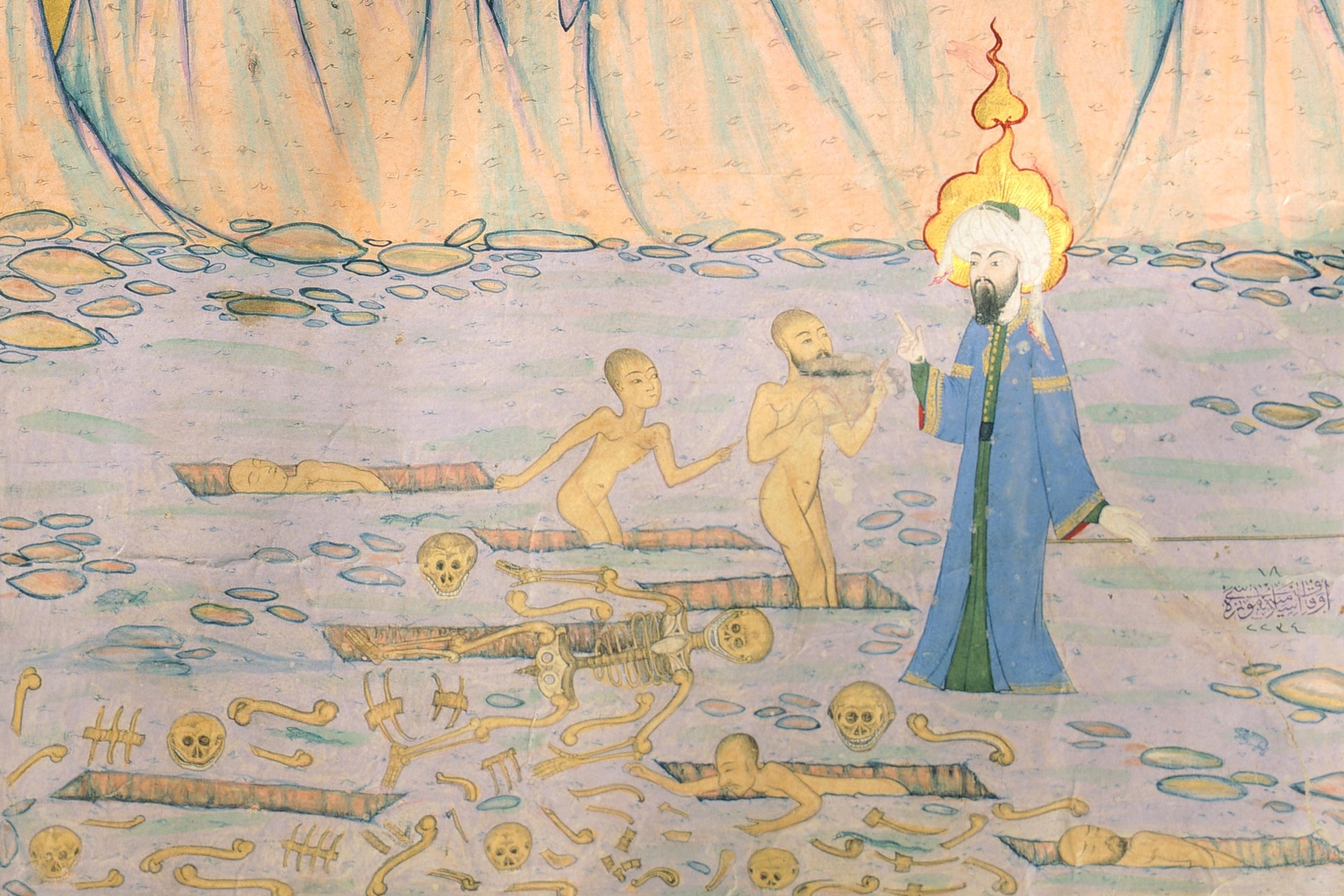

In addition to specialist works on sexual medicine such as Constantine’s On Coitus and another work of the same name by the Hebrew physician Maimonides (1138-1204), many of the most influential scholars of medieval Persian pharmacology, such as Ibn Sina (known to Europeans as Avicenna) and Al-Rāzī (also known as Rhazes) described aphrodisiac substances within their larger works of general medicine. Aphrodisiac substances were mainstream in medieval Middle Eastern traditions, and their use was understood to be both valuable and appropriate broadly within the bounds of Muslim, Christian and Jewish piety.

European physicians, prior to their engagement with the Middle East, and much like ancient Greek and Roman medicine, referred only scantily to a few aphrodisiac substances. The era of heightened spice trade after 1400 saw the increased transport of food and medicinal products from East Asia, India and the Middle East into Europe. Following the thriving activities of Muslim sea-traders and the revival of the overland spice trade in the 15th century, Latin pharmacopoeias (books listing the effects of medicinal drugs) began describing what was suddenly considered a distinct class of substances: aphrodisiaca. They were thought useful for several specific purposes: firstly, to increase seed (fertility) in both men and women, therefore enabling conception; secondly, to counteract the spells of witches that caused impotence and sterility; thirdly, to rejuvenate old men, acting both as revivifiers and as general-purpose sexual stimulants. Similar concepts of aphrodisiac use for stimulating both lust and conception in men and women, and for increasing older men’s sexual capacities, are detailed both in the work of the Persian physician Al-Tusī (1201-74), and in Constantine’s De Coitu. However, the use of them to combat witchcraft spells appears novel to early modern Christian cultures.

Pope Gregory IX’s 13th-century decree, De frigidis et maleficus, et impotentia coeundi (‘On the Frigid and Spellbound, and Coitally Impotent’) had named a new crime of sorcery that became a reference for theological concerns about marital relations for several centuries afterwards: malificium (witches spells) causing frigiditas (impotence). It was thought that both the Devil himself and the witches who were his servants had the power to inflict impotence and infertility via magical spells to thwart a married couple’s procreative attempts. The infamous Latin text known as the Malleus Maleficarum (1486), or ‘Hammer of Witches, devoted separate sections to the questions of ‘Whether Witches can Hebetate the Powers of Generation or Obstruct the Venereal Act’, and ‘Whether Witches may work some Prestidigatory Illusion so that the Male Organ appears to be entirely removed and separate from the Body’.

In 17th-century France, there were also several trials of people accused of sorcery that supposedly deprived men of their sexual capacity. Witchcraft was believed to be able to repel lovers from each other, to suspend a man’s desire for coitus, to corrupt a man’s mind to make his wife appear repulsive, to make a man have sex with women other than his wife, to prevent erections, seminal flow, or to disturb the natural heat of the penis and make the seed too cold for conception to occur. Conception was thought vulnerable to witches’ use of herbs, stones, amulets, spells or enchantments. Women were sometimes seen as the victims of such spells, but most examples referred to men being targeted and hence being the ones needing aphrodisiacs to counter the spell.

Since natural objects could be enchanted, the reverse was also true: bewitched individuals could be protected or cured by natural remedies. While medical writers advised people who believed themselves to be bewitched with maleficium to use prayer, they also considered pharmacological remedies to work by overpowering the enchantments and spells that diminished desire. Sea holly, civet’s penis, St John’s wort mixed with ragwort, horny goat weed and a decoction of columbine to wash the genitals are some examples of the aphrodisiacs used to prevent or cure the effects of infertility-inducing maleficia on the genitals.

Early modern medical scholars generally considered women’s pleasure as being as necessary for conception as men’s, making aphrodisiacs commonly prescribed for general fertility purposes. Catholic theologians advised married couples to avoid sexual pleasure as much as possible – since it was the Devil’s gateway – and yet the claim of aphrodisiacs to defeat witches’ spells meant that they were still tolerated. In Protestant cultures too, medical writers often suggested that aphrodisiacs would help conception. The Dutch physician Laevinus Lemnius (1505-68) recognised that babies could still be made without a woman’s pleasure in sex, but he thought that the children of such couplings would turn out to be lazy and stupid.

The use of aphrodisiacs in counteracting witchcraft spells in the 16th to 18th centuries is partly why modern biomedicine developed a dismissive view of them in the context of increasing scepticism of the supernatural. By the early 18th century, many European doctors, such as the English physician William Salmon, the German pharmacist Michael Ettmüller, and the German surgeon Mattheus Purmann viewed believers of infertility magic to be superstitious and gullible. Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, medical writers became increasingly sceptical of the notion of infertility magic; and, by the end of the 18th century, claims about sexual maleficia were widely disregarded throughout Europe.

Strikingly, premodern aphrodisiacs in Middle Eastern cultures rarely claimed to be remedying something that was thought broken, unlike both the early modern European aphrodisiacs used against witches’ spells and the modern pharmaceuticals, both hormonal and the Viagra-type, that claim to be restoring something deficient or counteracting the purported negative effects of ageing on libido. By contrast, products such as deer musk (secreted from the chest glands of central Asian mountain deer) and ambergris (a concretion of squid beaks excreted from the intestines of sperm whales) were traded extensively as prized luxury goods throughout Asia, the Middle East and Europe between 1500-1900 and were mentioned in many European pharmacopoeias of this period as potent aphrodisiacs. They were coveted and enjoyed by numerous cultures, not as remedies against sexual pathology, but as fragrant and delightful enhancements that were also prescribed as general health tonic products. They were also prized as much in perfume production as they were in medicine. When medical products travel the globe, the meanings within which they were contained in one culture can be radically reinvented in another – and often something is lost.