We all experience emotions, but we certainly don’t all handle them in the same way. Some people are sensitive and ride frequent ups and downs. By contrast, others are gifted with a thick skin and an even temperament. In the psychological jargon, they are highly skilled at emotional regulation. Perhaps you can think of friends, family or colleagues in your own life who match this description.

At the same time, there’s a social side to managing emotions. Many of us have friends or relatives who are able to provide steady emotional support. When we’re down, stressed or feeling overwhelmed, these are the people who offer a shoulder to cry on. They’re skilled at helping us regain perspective and return to an even keel.

Have you ever wondered if these groups – the folks who can manage their own emotions well, and those who are good at supporting others – are actually the same people? The answer could have a bearing on who we turn to for help, and on how we see ourselves and whether we’re equipped to be there for others.

‘I’m sure if you asked some people about this … they would say, “Well, of course, I know this person who is really great at helping others, but maybe not as good at regulating their own emotions,” or, “I know this person who is just wonderful at both,”’ says Maya Tamir, the director of the Emotion and Self-Regulation Laboratory at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. ‘But the lovely thing about science is it helps us put these intuitions aside and study these things as objectively as possible.’

The ability to manage one’s own emotions has long been recognised as one of the most important aspects of personality. People who have more stable emotions and are more resilient are said to be low in neuroticism – and they tend to enjoy a raft of advantages in life, including better physical health and lower risk of depression and anxiety.

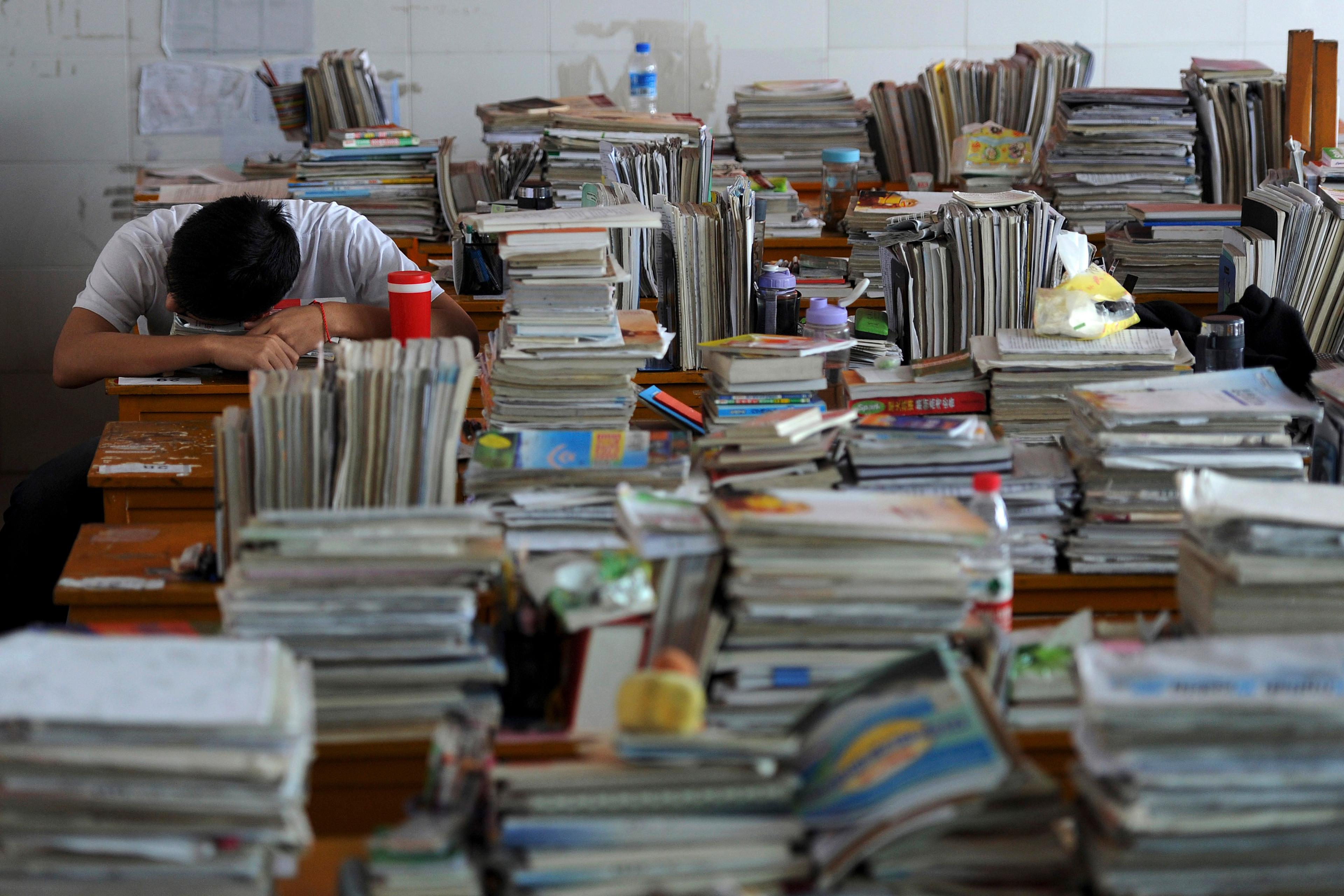

Helping others with their emotions can leave both parties feeling uplifted

Researchers have studied the different strategies that people use to regulate their emotions, such as distraction or reappraisal (reframing difficulties in a more positive light). And they’ve looked into the ways that emotionally stable people think differently from people who are more sensitive. For instance, there’s evidence that people who are skilled at regulating their emotions find it easier to recall more positive memories.

Meanwhile, there’s also a much newer field of study focused on people’s ability to help regulate the emotions of others. Research in this area has shown that helping others with their emotions can leave both parties feeling uplifted, and that – as with self-regulation – certain strategies are more effective than others. For instance, one study found that a particularly effective approach is to help someone positively reframe their difficult experience – imagine helping a friend reinterpret a stressful day at a new job as a valuable learning experience.

Other research indicates that we’re more likely to make the effort to regulate the emotions of people who are close to us. But it also suggests that, in those situations, we aren’t necessarily going very far to help soothe the person, often sticking to behaviours such as simply listening to them describe their difficult emotions. ‘These kinds of strategies may be important, not for changing the emotions you have, but for maintaining social bonds,’ says Carolyn MacCann, a psychologist at the University of Sydney, who co-authored this research.

While psychologists have been busy studying these two sides of emotion regulation – the individual dimension and the social dimension – there was until recently barely any study of how the two are related to one another. This is what inspired Tamir, her PhD student Noa Boker Segal, and their colleagues to conduct new research in which they compared people’s own emotional regulation ability and their ability to help other people with their emotions.

The study, led by Segal, involved 128 paired participants, each of whom attempted to regulate their own emotions as they looked at disturbing pictures. In another situation, some of the participants were asked to regulate the emotions of a partner as they viewed the pictures. ‘We had a range of pictures,’ says Segal, including images with negative associations, such as livestock in cages, and some that were ‘more graphic, such as burns and injuries’. A comparison of participants’ emotional states before and after they looked at the images provided a metric of how well they had kept their (and their partners’) emotions in check.

People who effectively managed their own emotions actually tended to be worse at helping someone else

Surprisingly, the participants who were better able to regulate their own emotions did not tend to be more skilled at helping someone else manage theirs. ‘I found it surprising based on everyday experience, but, more than that, based on the literature that suggests if you have a set of skills, it shouldn’t matter if you employ those skills to regulate one target or another,’ Tamir says. ‘And yet it turns out that maybe these are not the same skills. Maybe different types of skills are required.’

That’s exactly what the data suggested. Among people who effectively managed their own emotions during the study, one of the emotion-regulation strategies they said they typically deployed in their lives was distraction – for example, trying to think of something else while having an upsetting experience. Yet these same people who used distraction and effectively managed their own emotions actually tended to be worse at helping someone else regulate their emotions.

‘Sometimes we’re really good at shutting the world out,’ says Tamir. ‘And that can help us feel better. But when we shut the world out, we’re also shutting out other people.’ And so, she says, forms of emotion regulation like distraction ‘could be helpful to us, but could also disconnect us from other people, and would ironically render us less effective in helping other people deal with their emotions.’

It was a similar story for the self-regulation strategies of ‘situation selection’ (doing something to change the situation) and ‘suppression’ (making an effort to not express one’s emotions). People who said they used these strategies more themselves tended to be better at managing their own emotions during the study, but they were no better than average at regulating others’ emotions.

Of course, this is not the final word on the question of how self- and other-focused emotion regulation abilities are related. Perhaps most importantly, the study involved people who were meeting for the first time, rather than friends or family. Segal and Tamir already have further studies underway that suggest this is an important factor. Although the newer findings aren’t yet public, Tamir says they suggest that ‘the closer you are to another person, the more likely you are to actually regulate yourself and others in similar ways.’ She adds, ‘What we find with strangers may not necessarily characterise what we find in close relationships.’

In future research, they also want to flip things around to ask whether some people are better at being helped by others. ‘We typically attribute success to the [emotional] regulator,’ says Tamir. ‘But, you know, maybe some people are better able to rely on others … It could even be that the receiver is more influential than the giver. We don’t know. But that’s something that we are looking into.’

There’s an uplifting coda to this story. In addition to comparing people’s individual and social emotion-regulation abilities, Segal and Tamir also looked into the psychological consequences of trying to soothe someone else’s emotions. Their findings convey an encouraging message: when we try to comfort and support others, it seems everyone wins. The results suggested that attempts to help manage someone else’s emotions tended to leave both the supporter and the supported person feeling more positive afterwards. ‘Helping others, even strangers for that matter, can really help you feel better, or decrease your negative emotions under some circumstances,’ says Segal. ‘So I think that’s a very positive takeaway.’

Replicating earlier research on the social side of emotional regulation, the team also found that when one person attempts to help another person with their emotions, it can make both people feel closer to each other. In particular, this was the case for people who were better at regulating others’ emotions, while it was unrelated to how good they were at coping themselves.

These findings seem wonderfully encouraging for anyone who is emotionally sensitive and doesn’t exactly feel like a model of resilience. ‘Even if you struggle with your own emotions, that doesn’t necessarily mean that you won’t be able to help others,’ says Tamir. ‘And if you do help others, maybe that’s a way to actually make yourself feel better – and bring you closer to others.’