Alone in your house at bedtime, you settle in, ready for a good night’s rest when, suddenly, you hear a loud bang. Your heart starts racing, your breathing gets more rapid, and you become acutely aware of your surroundings. What do you do next? Shoot first and ask questions later, hide in your closet behind your clothes, or stay in bed trying not to make a sound? These choices are known, respectively, as the fight, flight and freeze responses to fear. Even if you haven’t experienced this exact scenario, you’ve probably been through something similar. We’ve all experienced fear.

Following Charles Darwin’s book On the Origin of Species (1859), evolutionary theorists have proposed that fear is a universal emotion that evolved to support survival. Fear sharpens the senses to potential dangers while preparing the body for fight or flight. It’s a call to action. However, what we fear, and how much fear we feel, might not be universal after all.

We’ve had the opportunity to learn how culture can shape fear from working with the Mapuche, the Indigenous people who live in Chile and Argentina, in the southern cone of South America. The Mapuche have a long warrior history; one of the very few cultures able to stop the advancement of the Inka empire in the late 1400s, they also held off Spanish rule for more than 300 years. It took the dual efforts of the Chilean and Argentinian militaries to finally defeat them in the late-19th century. Since then, they’ve struggled against considerable encroachment into their way of life and the land upon which they live.

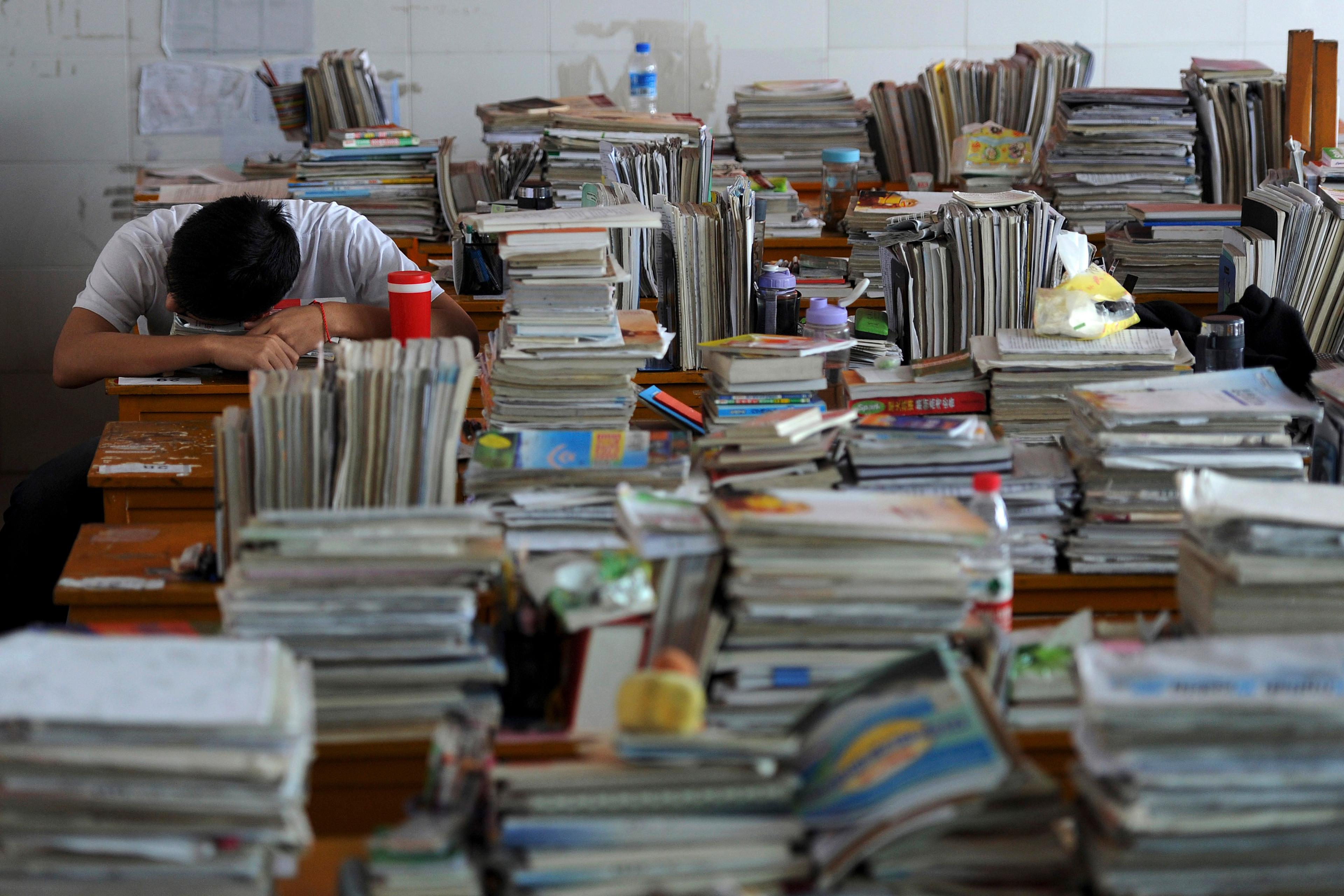

Nevertheless, the Mapuche have retained some independence, along with many of their spiritual beliefs and practices. Although many Mapuche have migrated to the cities for economic reasons, a large number maintain a more traditional agrarian lifestyle, characterised by small dwellings spaced to accommodate livestock and farming. Children spend most of their time in school or with family, learning about and caring for the land. Today, the Mapuche continue their battle against the subjugation of the land they are committed to, and they strive to protect and maintain their own culture.

We conducted lengthy interviews with the Mapuche – visiting families in their homes, drinking mate (a traditional caffeine-based brew) together – and discovered their distinctive way of thinking about, and reacting to, fear. A strong theme that surprised us was the clarity and consistency with which parents and elders described fear as having no value, saying that children should outgrow their early fears. The common sentiment was: ‘I do not feel fear; I feel respect.’

When we further probed parents and elders about these beliefs, they told us that fear isn’t useful and shouldn’t be felt. They argued that fear is debilitating and paralysing, and should be replaced with unconditional respect (ie, respect given to all life, human or nonhuman). In the Mapuche culture, respect seems to alleviate, and even replace, fear. The Mapuche believe that all elements of the universe are interconnected and deserve respect. They teach children to give reverence to the air, water and land, along with all the living creatures that inhabit these spaces.

It’s important to note that the Mapuche don’t try to suppress their children’s fear, but to transform it into respect. One way they do this is by helping children to feel secure and comfortable in potentially scary situations and to interpret those situations in a moral way. For example, they bring their children to bed with them or cuddle with them when they experience fear (eg, thunder at night) and they provide alternative explanations that respect the rights of natural phenomena to have their time for expression (eg, it’s the thunder’s turn to play now).

This led us to wonder, could there be advantages to prioritising respect over fear? Research suggests that respect fosters positive interactions between groups, reduces conflict and facilitates working together to create solutions to discord. Perhaps this is because respect embraces differences and advocates interconnectedness, rather than promoting hierarchies and subjugation of one force, or person, over another.

For a culture whose history is fraught with war, fear might not be useful in the way that evolutionary psychology suggests, and could even be detrimental in the context of mobilising a group for battle. Fear is reactive, whereas respect is deliberate and thoughtful.

So how would someone who starts from a place of respect, like the Mapuche do, react to the mundane fear-inducing scenario we posed above? We believe that such a person, rather than fighting, fleeing or freezing, would approach the scenario with curiosity.

This is not to say that the Mapuche are oblivious to danger, as they’ve been adeptly fighting various assaults for centuries, but they recognise the power and intrinsic value of others. Perhaps they would suggest that we grab a blunt object, such as a baseball bat, and cautiously investigate the situation, knowing that we’d have the means to protect ourselves, but also knowing that it might not be necessary. They might also suggest that feeling fear would only get in the way of effective thinking, stifling our openness and curiosity about the possibilities of the situation.

One of us (Amy Halberstadt) remembers the true story of a great-aunt who, after surprising a burglar in her kitchen, sat down with him over a cup of coffee, talked with him through the night, and sent him off in the morning with a different set of goals than burglary. We never learnt the outcome for the burglar, but we think the Mapuche would be amused by, yet approve of and understand, this way of responding.

We continue to think about how respect, in place of fear, could benefit Western culture. Our lab also investigates racial biases, and how cultural messages and stereotypes can lead white people to misinterpret the emotions and intentions of black people. For instance, we recently tested trainee teachers, nearly all of them white, and found that they perceived black children to be angry more often than white children, even when they were actually expressing other emotions, such as happiness, disgust or surprise. Perceiving that other people are angry invokes feelings of vulnerability, which breeds fear.

You might be wondering how these strands of our work connect together. Our thinking is that the beliefs of the Mapuche – that all living things deserve respect, and that we are all part of the same whole – might help to reduce the potentially fear-inducing beliefs that cause people to see anger in black children even when those children aren’t angry. The implicit beliefs that can stoke prejudice are quick and automatic, and often reflect wider societal messages about why certain groups should be feared. Transforming fear into respect could encourage us to respond more thoughtfully, rather than engaging in automatic (and fearful) reactions. Instead, if we approached every interaction with respect, we would see more clearly the emotions of people that we view as different, decreasing our unhelpful implicit beliefs about them.

Our work with the Mapuche might prompt Western parents and teachers to ponder how their beliefs about, and responses to, children’s emotions could have lasting effects. More generally, by recognising that emotions are cultivated within cultures, we might consider how to transform our emotions into actions and beliefs with more beneficial outcomes. Our hope is that, by approaching people from different backgrounds and cultures with respect and a sense of our interconnectedness, rather than with fear, we can help to bridge some of the divides that we face today.