‘The Karen buried her hatchet and submitted to the straight, fat hillbilly’s rule of thumb that gay ladies and gentlemen of colour should be blackballed from the powwow.’

This sentence offends almost everyone, according to the inclusive language guidelines being drawn up by universities, corporations and public bodies in the Western world. Their guidelines would have struck a red line through every word.

What I should have written was: ‘The entitled white woman, in the interests of peace, accepted the default ruling of the obese, heterosexual person from the Ozarks that LGBTQ+ and BIPOC should not be invited to the get-together.’

Obviously, this is meant satirically. No writer worth his or her (or their) salt would write such a sentence (for aesthetic reasons, hopefully, and not because it offends). But the fact that I feel the need to explain myself at all suggests the presence of an intimidating new force in society, a kind of thought virus that has infected most organisations and political parties, on the Right and Left, the key symptom of which is an obsession with textual ‘purity’, that is, language stripped of words and phrases they deem offensive.

Yet, in trying to create a language that offends no one, they offend almost everyone.

Why are we so afraid to use words freely, to offend with impunity? Whence arose this fetish for the ‘purity’ of the text? I trace the origins of this obsession with textual purity to the triumph of linguistic philosophy in the early 20th century. Let’s alight on a few key moments in that story to understand how we got here.

Richard Rorty, the editor of the seminal anthology The Linguistic Turn: Essays in Philosophical Method (1992), described ‘linguistic philosophy’ as ‘the view that philosophical problems are problems which may be solved (or dissolved) either by reforming language, or by understanding more about the language we presently use’. The elevation of language to such dizzy eminence divided philosophers: some thought it the greatest insight of all time; others were disgusted by what they interpreted as ‘a sign of the sickness of our souls, a revolt against reason itself’.

The ‘linguistic turn’ on which the new thinking hinged was a radical reappraisal of the very purpose of philosophy. It swung away from the grand philosophical systems of the 18th and 19th centuries (as adumbrated by G W F Hegel, Immanuel Kant, Arthur Schopenhauer and lesser lights), and divided into two streams of thought – ‘analytic’ and ‘continental’ philosophy – which disputed much but shared this: an obsession with language and the limits of meaningful language.

Wittgenstein conceived of the world as an agglomeration of facts and not atomic objects

The thinker who did most to propel philosophy into the orbit of linguistics was an Austrian logician and star pupil of Bertrand Russell’s called Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951). He blamed what he saw as the confusion in philosophy on ‘the misunderstanding of the logic of our language’, as he recounted in the first of his two philosophical works, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921).

The ‘whole meaning’ of this book, explained Wittgenstein, was to define the limits of meaningful language and, by extension, meaningful thought: ‘What can be said at all can be said clearly; and whereof one cannot speak thereof one must be silent. The book will, therefore, draw a limit to thinking, or rather – not to thinking, but to the expression of thoughts.’ In a letter to Russell, he was more specific: language, he wrote, was the same as thought: ‘The main point [of the Tractatus] is the theory of what can be expressed … by language – (and, which comes to the same, what can be thought).’

The Tractatus is built on seven broad propositions containing 525 declarative statements that explore Wittgenstein’s conception of the world as an agglomeration of facts and not, as most people suppose, atomic objects. Statement 4.002 argues that language is not a mirror of the mind, but a cloak over the actual character of the speaker:

Language disguises the thought; so that from the external form of the clothes one cannot infer the form of the thought they clothe, because the external form of the clothes is constructed with quite another object than to let the form of the body be recognised.

The Tractatus persuaded Wittgenstein that he had solved the problems of philosophy, and that we could all go home and relax. For 30 years nobody contradicted him, until he did, in his second book, Philosophical Investigations, published in 1953, two years after his death, which revised and expanded his ideas about the limits of language.

A brace of the 20th century’s finest minds found themselves thinking and writing in the shadow of Wittgenstein. The English logical positivist A J ‘Freddie’ Ayer was one: ‘[T]he function of the philosopher is not to devise speculative theories which require to be validated in experience,’ he observed in Language, Truth and Logic (1936), ‘but to elicit the consequences of our linguistic usages.’ The German philosopher Martin Heidegger was another: ‘It is in words and language that things first come into being and are,’ he noted in An Introduction to Metaphysics (1953), and he built on that theme in On the Way to Language (1959). It was language that spoke, not human beings, he noted; we were merely participants in a form of communication that preceded us.

Let’s fast-forward to that fever of French intellectuals living in Paris in the 1960s, one of whom dared to reconstrue Wittgenstein’s interpretation of the limits of language by arguing that language was the limit.

The culprit was the Algerian-born French philosopher Jacques Derrida (1930-2004), who said: ‘There is nothing outside the text.’ This statement cast ‘the text’ – and the text alone – as a skeleton key with the power to open the mind of the writer or speaker.

No statement more powerfully accelerated the arrival of today’s culture wars. Derrida’s ideas thrilled the militant Left, for whom all the world was suddenly reducible to a ‘text’; and had the effect of kryptonite on conservatives and traditionalists who yearned for the return of objective order and a hierarchy of values, not words. A third, less voluble, group of critics recoiled from the suggestion that words alone were a mirror of our minds, and rejected the Derridean idea that all forms of expression were merely ‘points of view’ in a world that was rapidly being ‘deconstructed’.

‘Deconstructionism’, Derrida’s gift to the world, was a way of thinking that consigned all communication (visual, literary, musical, propaganda) to the status of ‘discourses’ or ‘narratives’ that could be ‘dismantled’ and reassessed according to new sets of social criteria.

An advertising jingle, a tabloid headline or a travel brochure were no less ‘valid’ as portrayals of the human lot than fine art

Derrida argued that if the visual arts, music and literature had been ‘constructed’ to reflect certain traditional or elitist values, then they could just as easily be ‘deconstructed’ – that is, stripped of their old context and re-examined according to new cultural reference points, as the writer Peter Salmon (Derrida’s biographer) explains.

Any work of art might be reassessed through a new cultural prism: Marxist, feminist, gay, trans, class, and others. So too could an advertisement, the legal system, the government, God, your very identity. Little wonder Derrida is hated by the Right as the father of ‘cultural Marxism’ and feted by the Left as the anatomiser of cultural orthodoxy.

Those of us who dare to read William Shakespeare’s plays as indivisible portraits of the human lot apparently failed to understand the political amenability of Hamlet or King Lear or Macbeth to Marxist, feminist and gay readings, in the view of the Derridean deconstructionists. That is, we missed the ‘real’ (that is, deconstructed) meaning of Shakespeare’s plays, which only becomes clear after we dismantle and recontextualise ‘the text’ – for example, by applying a feminist reading of The Taming of the Shrew or a Marxist reading of The Tempest. Both readings, according to Derridean theory, are perfectly valid, possibly more ‘relevant’ interpretations of the plays.

The ‘text’ thus exerted a mysterious power over the deconstructionist’s mind, to the extent that an advertising jingle, a tabloid headline or a travel brochure were no less ‘valid’ as portrayals of the human lot than fine art and great literature. It all depended on your point of view, to which everything was reducible. There was no such thing as ‘objective beauty’ or ‘objective truth’, only a cacophony of subjective opinions. And therein lay the seedbed of what postmodernists call ‘postmodernism’, an intellectual movement that tends to be defined by what it isn’t, and is as difficult to observe as a quantum particle.

The error of the Derridean deconstructionists – and today’s textual fetishists – is that they presume to judge the ‘value’ or ‘relevance’ of a text according to their own narrow cultural criteria.

They refused to accept that the finest artistic productions of the human mind are not divisible or reducible to a social construct. They’re neither ‘relevant’ nor ‘irrelevant’. They transcend cultures, classes and genders, and appeal to something in us all. They’re unbound by a social or historical rereading precisely because they’re not another ‘narrative’ or ‘discourse’, in the Derridean sense. They surmount the dreary conflict of nations, classes and genders and inspire all human thought and feeling, regardless of ‘context’. They’re eternally authentic, unamenable to the kneading hand of the ‘deconstructionist’. They shrug off postmodern attempts to lay them on a slab and fillet them. They are, in short, fully formed in space and time, and ‘undeconstructible’. Those who presume to ‘deconstruct’ three examples – Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy and Jane Austen’s novels – are like Lilliputians trying to chain down a winged goddess.

What has all this to do with language inclusion guides, censorship and textual fetishism? I contend that Western universities, corporations and public organisations, in line with the fact that revolutionary ideas usually take decades to infect the body politic, have absorbed, consciously or not, the Derridean idea that there is ‘nothing outside the text’.

The trouble is, many in the ‘Anglo-Saxon world’ (as the French delight in calling English-speaking countries) failed to understand that Derrida was a French intellectual. His ideas were not prescriptive; they’re meant to be chewed on, debated and spat out, if need be.

Instead, the English-speaking linguistic police seized on ‘the text’ and invested language with a kind of revelatory power, making words and phrases the measure of our minds – indeed, the very content of our characters.

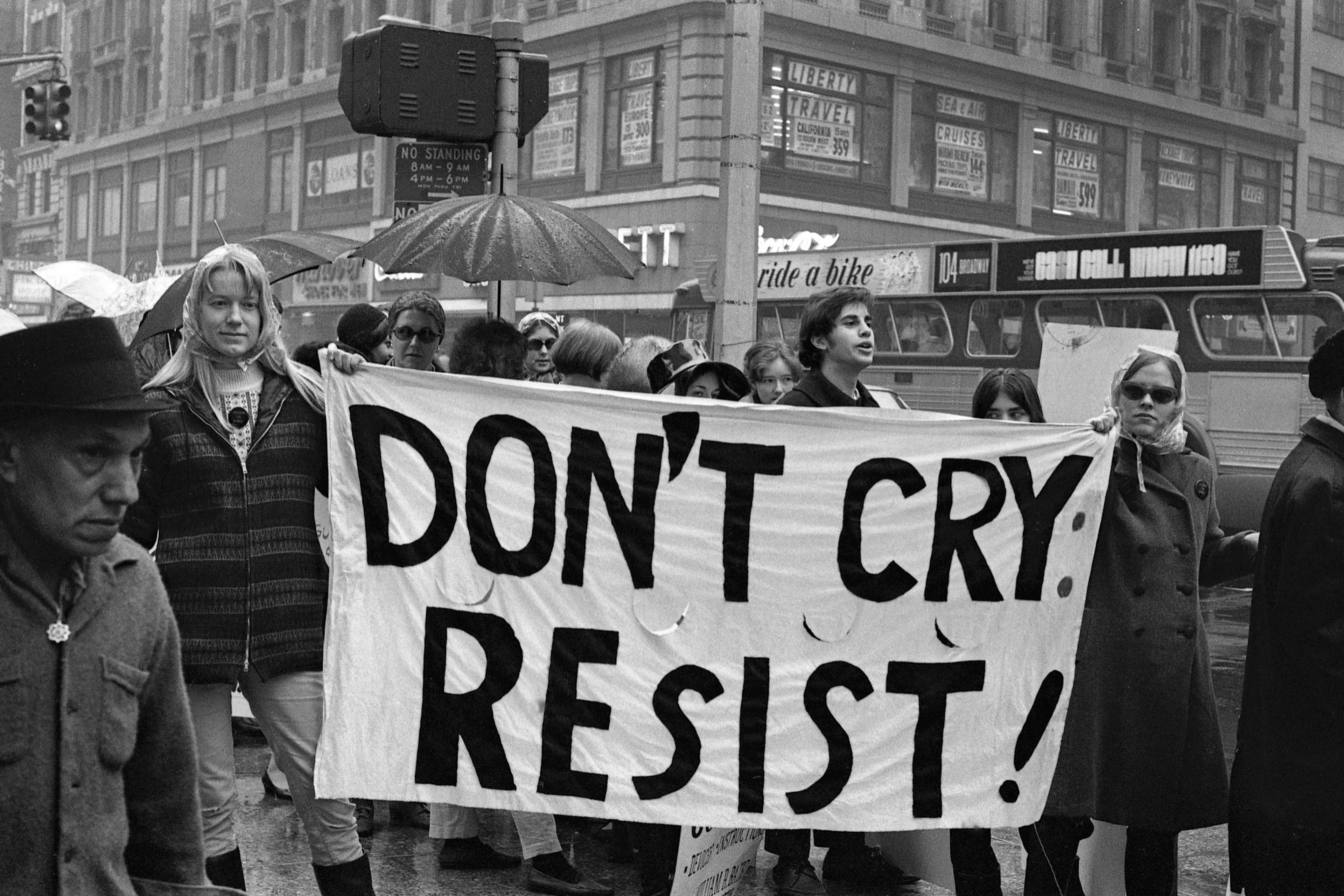

Wittingly or not, the cancellation culture warriors who ban books or draft language inclusion guides use the tools of Derridean deconstructionists to shape and control the human mind. Your words express a point of view that is unacceptable to the arbiters of linguistic correctness on both the Right and Left of politics.

Those who presume to ban texts they find offensive threaten a lot more than our right to free speech

By editing the language of usage they deem unacceptable, they then devise approved words, phrases and books that dictate how we should think. And if we disobey and continue uttering or writing non-inclusive or unchristian things, they threaten to ‘cancel our minds’ by attacking our characters, the very sense of our ‘selves’, as Greg Lukianoff and Rikki Schlott chillingly demonstrate in their book The Canceling of the American Mind: Cancel Culture Undermines Trust and Threatens Us All – But There Is a Solution (2023).

In this sense, those who presume to ban or delete texts they find offensive threaten a lot more than our right to free speech. They menace the freedom to think. They proceed on the ridiculous assumption that if they eradicate offensive language, they’ll eradicate offensive people. By this inquisitorial way of thinking, our spoken language alone becomes the arbiter of whether we’re nice or nasty people, in isolation from our private thoughts and motives. A nice young student who ticks all the approved linguistic standards might harbour murderous, racist and ableist ideas but who would know?

That our choice of language should condemn us is a ludicrous proposition, of course. It renders irrelevant the silent protest of our private thoughts. It completely ignores the motives behind language. It’s as if our spoken or written words were the only test of our value as human beings, and the silent dimensions of our psyche, the subconscious, the ‘soul’, the conscience, the ego, id and superego, indeed the entire Freudian, Jungian and psychotherapeutic tradition, were of no consequence.

For most of us, words are valves that relieve the pressure cooker of the brain, or simply the sounds that we lazily deploy to please or fill a void. Words are the ghosts of our thoughts, mere echoes of our ‘selves’. Only the finest poets seem able to marry their minds and their words.

And that is why banning words won’t make the world a better place. It’ll simply stifle the expression of thoughts that exist anyway. Words that offend should be argued with and met with words that counter-offend. That’s education, not cancellation, and it is the point of liberty. In sum, cancelling language won’t create a ‘safe space’. It’ll create a dystopia of textual fetishists: thought police mumbling in self-edited confusion.