Ten years ago, I was prescribed a non-penicillin antibiotic to clear up a routine urinary tract infection. Part of a broad group known as fluoroquinolones, the pills made me feel as dizzy as if I’d drunk the better part of a bottle of wine. I checked the leaflet, noted that ‘mild dizziness’ was an acknowledged side-effect, and kept going. Five days into the course, I suffered an adverse reaction that felt like a minor stroke. Momentary loss of motor function down one side, cranial pressure and, when I got to the accident and emergency department, blood pressure high enough to cause an imminent heart attack.

However, only after I was discharged did the real trouble kick in. A cursory look online would have told me that fluoroquinolones were linked anecdotally to a host of gothic side-effects. They’ve been on the United States market since 1987 and, since 2008 – courtesy of the Food and Drug Administration – they come issued with a ‘black-box’ label warning consumers and doctors of potential tendonitis and tendon rupture. But back then, in the United Kingdom, they were just being promoted to frontline use. The drugs are now also associated with irreversible peripheral neuropathy, potentially fatal liver and kidney damage, hypo- and hyperglycaemia, toxic psychosis, and spontaneous rupture not only of tendons but also muscles, ligaments and cartilage. Testimonies from online patient forums lamented head-pressure, muscle tremors, chronic muscle and joint pain, tinnitus, blurry vision, eye-floaters, snow-vision, rapid weight loss. The list was endless.

My principal symptom was a deep numb ache in both legs, combined with a constant feeling that my skin was lacerated from the knees downwards, as if I had just walked through stinging nettles – a prickly deep-freeze. At worst, it felt as if a Rottweiler had its teeth around both my ankles. At the time, making some of my living as a musician, I’d end up sitting flummoxed on the lip of the stage to play guitar, after it became too overwhelming to stand up. Later, I found out that this was what a peripheral neuropathy felt like: chronic nerve damage, in other words. Of course, I hoped these symptoms would go away. They didn’t. I still have irreparable nerve damage in my legs and feet. Like many people, I’ve learned to live with chronic pain, but have no way to alert the outside world that I am suffering.

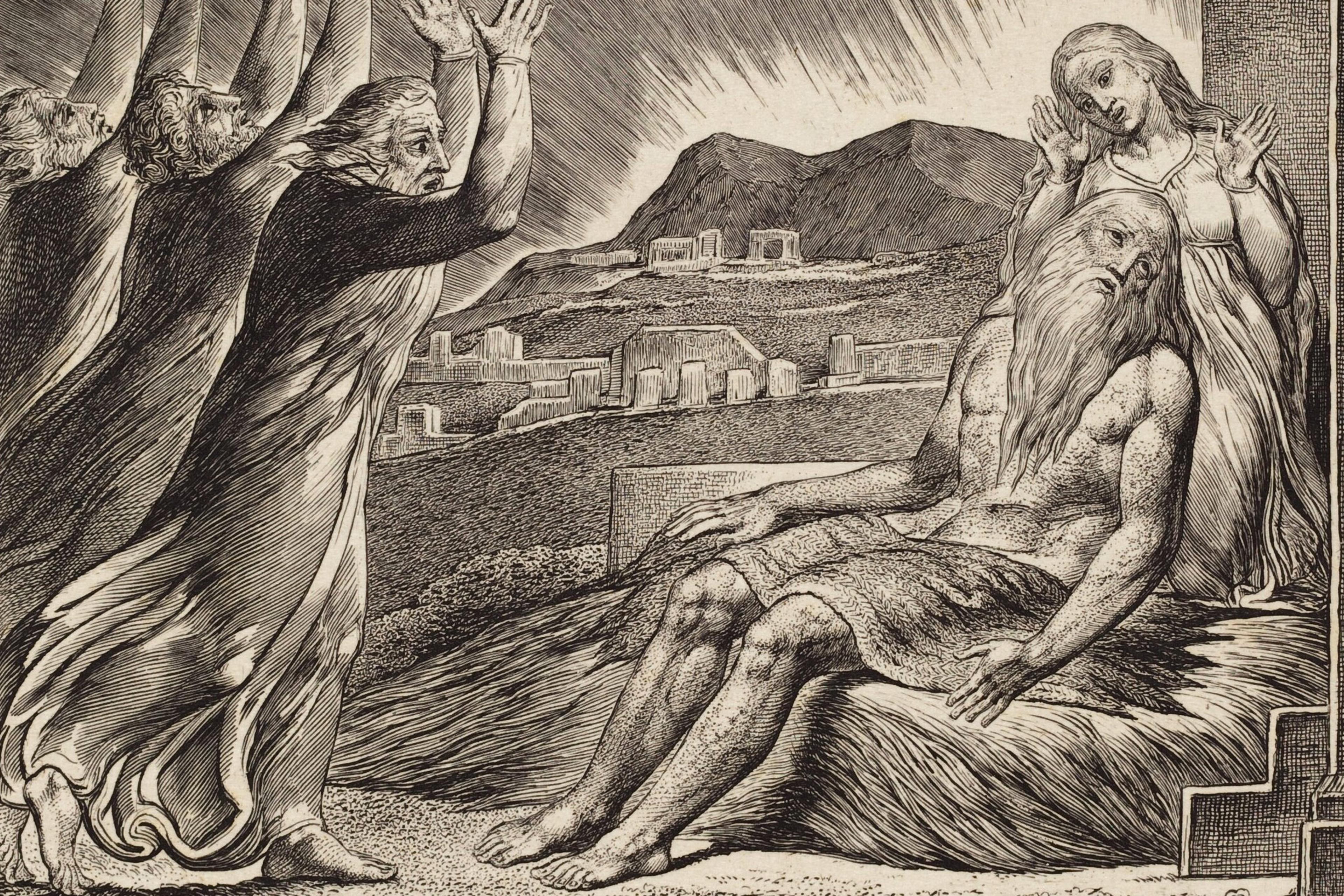

Perpetual pain is profoundly isolating. Its accompanying fatigue, deadening and depressing. Until pain was my constant companion, I never fully understood how alone in our bodies we really are. It’s a slog – a lifelong sentence. Sometimes I’d find myself counting how many years I might live, and wondering if I could stick it out. Could I do a decade of this? Two decades, three? The phrase ‘one day at a time’ fast becomes unhelpful when thinking about a natural lifespan, especially if it’s one of stoic endurance. Only the example of the French mathematician Blaise Pascal, who suffered searing migraines, brought me any kind of perspective. ‘Man is but a reed,’ he wrote in 1670, ‘the most feeble thing in nature. But he is a thinking reed.’ Maybe I could think my way out of my pain – even welcome it, as the Buddhist mantra encourages us to do.

The most common experience of chronic pain is the inability to concentrate on what is immediately in front of you, on the task at hand, or on what people around you are saying. Your only yearning is that it should cease. The words of Winston Smith in George Orwell’s novel 1984 are apposite here: ‘Of pain you could wish only one thing: that it should stop … In the face of pain there are no heroes.’ The strange dance of performing the well body – enduring long dinners, plays and trips to the cinema while my legs screamed in protest; begging a walking companion to slow down for fear my legs would give way – became a full-time job. Also, a kind of farce, or lie. There’s a dissonance at play that feels dishonest, arising from an internalised pressure to appear well. We don’t want to burden others with our woes, after all: in this, those suffering chronic pain feel an affinity with those battling depression. What’s more, I wouldn’t have felt so equivocal to pretend wellness if I didn’t have the experience of actual wellness to compare it with.

People take their cues from obvious signifiers: I didn’t use a wheelchair or walk with a stick, I didn’t wear a leg brace or limp, and my legs didn’t appear damaged: ergo, my pain must be manageable. Worse, still, was any imputation that the pain was something I merely imagined – or, given the current wellness environment of clean eating, good living, mindfulness and self-optimisation, the idea that I must be some sort of snowflake for not being able to master it.

In fact, not long after my exposure to fluoroquinolones, I did have one visible symptom: I exhibited a considerable and noticeable loss of weight (rapid weight loss being another acknowledged side-effect of being ‘floxed’). People asked after me, although, mostly, the reaction was flattery. They’d comment on how ‘trim’ I looked. Since unexplained weight loss is officially a medical concern, I did eventually get checked out for cancer, with the results coming back negative. Once again, it was brought home to me that only if you look different are you different. Still, the medical attention made me feel less isolated, more acknowledged, even vindicated. I became acutely aware of how we live in our bodies. The corporeal is all. If ‘grief lives in the mouth’, as Martin Amis wrote about his dental woes in his memoir Experience (2000), then, for me, it lived in my legs.

Of course, my first instinct had been to seek a cure. When conventional painkillers failed, the only balm was a hot bath, or alcohol. And lots of it. For a couple of years, I sought out experts: first at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, where I underwent inconclusive nerve conduction tests, then a series of consultant rheumatologists. Finally, a pain consultant prescribed a course of hardcore pills most often used in the treatment of epilepsy. Among the lengthy list of its possible side-effects was suicidal psychosis. The risk was all mine, he told me. I decided not to take it. Rather the Rottweiler than the straightjacket.

The one constant in all these consultations, I soon found out, was the skepticism I encountered in the medical establishment. This surprised me, coming across as an insult to the way I experienced my own body. Of course, the medical profession didn’t want to admit that something it prescribed might have injured me. There were legal considerations, too: if I were to rupture a tendon and find myself unable to work either as a writer or a musician, then I could legitimately sue for earnings lost. But short of that catastrophe, the level of damage I’d suffered was hard to quantify. As the writers Sonya Huber in Pain Woman Takes Your Keys (2017) and Abby Norman in Ask Me About My Uterus (2018) have shown, women and people of colour have more trouble getting their pain taken seriously – from endometriosis to menstrual pain.

Yet even for a white man like me, to present with pain, minus any visible symptoms, is to open himself up to being gaslit, or else summarily dismissed. Indeed, the final rheumatologist I consulted insisted that my pain was ‘all in my mind’. Given how the brain’s pain centres operate on a physiological level, he was right: pain literally is ‘all in the mind’. But this was not how he intended his diagnosis. At that moment, I realised that a poet might have offered more valuable help. As the 18th-century philosopher Anthony Ashley Cooper, the Third Earl of Shaftesbury noted when praising the sympathetic imagination of the poet, he alone knows ‘the inward form and structure of his fellow creatures’.

Ten years later, I’m resigned to living with a chronic condition that no one can see. None of today’s self-help regimes – from gluten-free diets to punishing workouts – help to ease my body’s malaise. ‘Get well soon,’ people used to say, when I first told them about being ‘floxed’. ‘Thanks,’ I’d mutter to myself, ‘I won’t.’ The only comfort I took from a consultant came during a visit to a charitable organisation that dealt with musicians’ injuries. ‘Bad luck,’ he said to me.

Yes, I thought, it is bad luck. For being in the minority that reacts adversely to that particular medicine. But good luck, too. I wasn’t battling cancer, unlike a couple of my friends, only a day-to-day reality I’d no choice but to accept. I learned the hard way that the body is never as robust as it seems to the outside observer. There is an upside too: my decade of chronic pain has been artistic gain. In my latest novel, Jacob’s Advice (2020), my narrator, struck down by fluoroquinolones, spends the book ‘performing the well body’, while elaborating on how such a life feels from the inside. Interiority, of course, is something fiction does better than any other art form. So maybe the poets will have the last word after all.