Picture this: you are waiting to check out at the grocery store, and in front of you is a baby in a stroller chewing on a small toy. Her tiny hands lose hold of the toy and she drops it but, instead of crying, she looks up at you with her large, round eyes, and breaks into a big smile and squealing laugh, before reaching up her chubby arm to wave right at you. Instantly, your mood starts improving, you find yourself feeling warm and fuzzy, and you might even want to go over and give her hand a good squeeze. Maybe you even let out an audible ‘Awww!’ You find yourself making a goofy expression: you’re smiling, lips puckered, chin raised, eyebrows pulled together and up toward your forehead. Noticing your response, others in line start looking at the stroller, and suddenly you are all making that same expression.

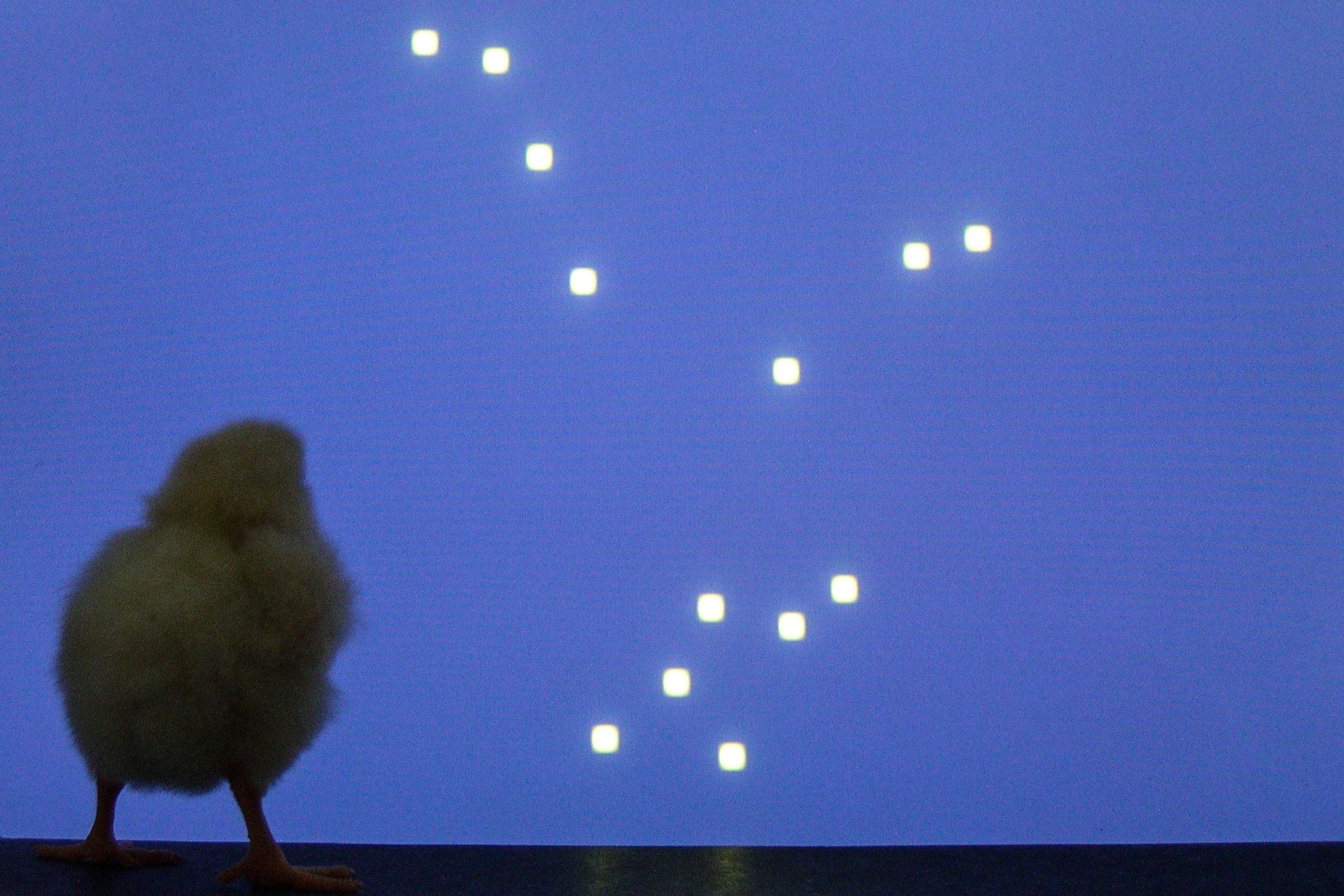

The adorable baby that triggers this response represents what the zoologist Konrad Lorenz in 1971 called the Kindchenschema, or ‘baby schema’ – a suite of physical traits that signal youthfulness and cuteness. The Kindchenschema involves features such as having large eyes, a round face and short, stubby limbs that often result in being uncoordinated or clumsy. It is quite typical in human infants as well as many baby animals, and has an almost magnetic pull on people.

Who among us hasn’t been drawn in by the cuteness of a puppy tripping over its own feet or a toddler waddling excitedly toward her parent? Fascination with cuteness extends across the human species. Around the world, people cannot get enough of anything reminiscent of these adorable traits. Most notably, if one visits the Harajuku neighbourhood in Tokyo, they will see the pinnacle of kawaii, or cute culture, on full display. Blocks of shops full of colourful, miniature characters with full Kindchenschema traits are separated only by scattered cafés where you play with actual small animals.

The distinctive human response to cuteness starts with how we behold certain people, animals and things. Research has shown that people have a specific way of responding to Kindchenschema that differs from how they respond to adult-like stimuli. This response involves a narrowing of one’s attention and a positive emotional experience focused toward the cute target (eg, a baby, a puppy, a kitten). Going further, there is growing empirical evidence that looking at cute faces is associated with various neurological and physiological changes. For instance, responding to cuteness activates reward structures in the brain. It also elicits a desire to care and protect. Imagine, for instance, that the baby in the stroller had gotten unbuckled and was on the verge of tumbling out headfirst to the floor; you would probably feel an intense urge to take action and protect her from falling. Taken together, the findings suggest that responding to cuteness involves a sense of wanting to provide care and feeling rewarded by the opportunity to do so.

This is not to say that providing care for infants is easy. Ask the parent of a young child, and you will likely hear something along the lines of: ‘I’m exhausted all the time, I feel like I’m drowning, this is so hard. But I’m happier than I’ve ever been, and one look at my child’s precious face and I know I wouldn’t change it for the world.’ Their parental love overrides the exhaustion, frustration and all the many challenges that come with caring for small children. This positive emotional state ignites a sense of wanting to care for the child; wanting to feed them, change their diapers, clean up their messes, rock them to sleep in the middle of the night. Moreover, this pull toward caring extends beyond the child’s parents. Grandparents, aunts and uncles or close friends might describe a similar experience of wanting to help care for the young child.

Cuteness makes us feel good because it is evolutionarily helpful to the species

At the root of this care is Kindchenschema and the human response to it, which I and other researchers are continuing to unpack. As a child grows out of their helplessness, and displays fewer and fewer Kindchenschema traits, a family’s love may remain unconditional, but the strong, emotional response that stokes a desire to provide constant care fades. Being cute helps keep young, infant-like children and animals safe and cared for.

Evolutionarily, this makes a lot of sense. For many species, humans chief among them, newborns are vulnerable and need care and protection in the environment outside their mother’s womb. If this care and protection is not provided, the newborn will not survive. By extension, if this pattern holds across the entire species, the species does not survive. However, providing care and protection to newborns is burdensome and costly (financially, yes, but also physically and psychologically). Thus, having a mechanism that makes people want to take on that burden is beneficial not only to the newborn, but to the species in general. The Kindchenschema, and the associated neurological and emotional responses to that cuteness, are precisely such a mechanism. We are not drawn to cuteness just because it makes us feel good. It makes us feel good because it is evolutionarily helpful to the species to have a driving force toward caring for the youngest and most vulnerable among us.

As with many emotional responses, it’s also useful to be able to express that one is in a state of responding to cuteness. For certain emotions, having recognisable expressive displays that do not require language – such as a prototypical facial expression, body language, or vocal inflection – is an important way to inform onlookers about one’s current state and how they, as onlookers, should respond. Not all emotional responses seem to come with a unique, nonverbal expressive response (think of gratitude, for instance). But emotional responses that do involve recognisable expressions are thought to have these in order to address particular evolved needs.

A high-pitched scream and a wide-eyed look communicate fear, and that one is in danger. If an onlooker sees this fear expression, they may decide to help the person in danger, or to look around for said danger so as to avoid it themselves. A scowl and a low-pitched growl communicate anger. By recognising when someone is angry and might try to harm those nearby, an onlooker can try to avoid the angry person, or make amends if they caused the anger. A smile and laughter communicate that one is amused or feeling joyful, so an onlooker might approach this person in order to share in the amusement.

Wordlessly expressing that one is responding to cuteness holds adaptive value for people

Similarly, people communicate that they are having an emotional response to cuteness through facial expressions and vocal inflection. When interacting with infants or baby animals, people will often speak with a high-pitched melodic inflection known as ‘parentese’. And in recent research, my colleagues and I have demonstrated that there is a prototypical facial expression people show when responding to cute, Kindchenschema targets. This expression, which I noted in the baby-in-the-stroller scenario, involves a combination of a genuine smile, bringing together and raising of the eyebrows, a raising of the chin, and a tightening of the lips (similar to what one’s mouth might do when saying ‘Aww!’ upon looking at something cute).

Not only is this expression one that people spontaneously produce when looking at cute babies and animals, but other people recognise the expression as a response to cuteness. This recognition was observed across groups from varying linguistic and ethnic backgrounds (ie, participants in the United States and China, and Syrian refugees). Our findings suggest that wordlessly expressing that one is responding to cuteness – and being able to recognise this response – holds adaptive value for people. Otherwise, we would not need to have such an expression or recognise it cross-culturally.

So, what purpose does the recognition of a cuteness expression serve? What are people communicating to onlookers when they visibly (and audibly) respond to cuteness in these ways? Although more research is needed to be able to fully address these questions, there are a couple of likely candidates for the primary purpose of this expressive display.

First, showing a cuteness response might signal directly to a child that you are safe and ready to provide them care. When a small child is in distress, or in an unfamiliar environment that may lead to distress, they will seek out care (eg, reaching for a parent; clutching a favourite soft toy). By speaking to a child in a gentle, calming way and displaying the associated facial expression, you could inadvertently be communicating to the child that you are motivated to care for and protect them.

Unconsciously, you recognise the importance of caring for something cute

Expressing a response to cuteness could also serve as a signal to other adults that there is a cute, vulnerable being present who needs to be cared for. This might inspire onlookers to move closer, to further assist in the caregiving, if needed. The expression might partly be signalling to other adults that we are seeking assistance with care – or that we mean a child no harm, and can be trusted to help keep them safe and cared for. Ancestrally, humans and several other mammalian species tended to engage in more communal caring for the young. Females, in particular, while primarily caring for their own offspring, lived in close-knit communities built on mutual cooperation that was aimed at promoting the safety and wellbeing of all youth in the community. Thus, perhaps expressing a cuteness response has long served as a way to communicate that one is a part of such a community, ready to help care for the young and vulnerable.

Whatever its primary function, it is clear that this response is signalling something of value to others. At a superficial level, seeing something cute and responding to it seems like it’s just good fun, almost trivial. Cuteness is warm and fuzzy; it distracts you from more serious things; it puts you in a good mood. But under the surface, so much more is going on. Cuteness likely distracts you from more serious things because, unconsciously, you recognise the importance of caring for something cute. It can put you in a good mood so that you want to keep engaging with it despite the difficulties that may come. We signal to others that we are responding to cuteness because it holds adaptive value and is important to do so. Cuteness may be fun, but it is not trivial.