It is not difficult to imagine feeling mentally overstuffed. Your thoughts race, your emotions surge, and you might do things such as lash out at people you care about, cry uncontrollably or make decisions you wouldn’t have made if you’d thought them through. Most people have felt this way at least once in their lives, usually during periods of intense stress.

But many people have also had a different kind of troubling experience: a feeling of emptiness. If you feel empty in this way, you might find that bad news doesn’t make you feel upset, that good news doesn’t make you feel happy. Some part of you knows you should feel something when important things happen, but you don’t. No matter how much effort you put into pursuing your goals, no matter how much others show you they care, or do things that would bother most people, everything just seems to filter out and you are left feeling little. Empty. You go through the motions, barely even noticing whether you are doing the dishes, driving your car or talking to a friend. You think this feeling will never change and nothing will ever mean anything. You are disconnected from the world, as if you’re watching it go by from the window of a train that is not going anywhere in particular.

If you have not had this experience, it may be challenging to imagine what it is like. It might even sound as if it could be a good thing, like the kind of healthy detachment pursued in religions such as Buddhism. But what I’ve described – subjective emptiness, or the feeling of absence from one’s own life, lack of fulfilment, forced existence and profound aloneness – is a serious mental health symptom. People who feel emptiness have problems in work and relationships, are at significantly higher risk for suicidal behaviour, and often have difficulties engaging in mental health treatment.

People who report feeling empty also typically report feeling too full of feelings

While both serene detachment and emptiness have to do with feeling disconnected from the world, there are important differences. Whereas detachment is associated with calm satisfaction, and something people work towards through meditation, emptiness is a dreaded state that people desperately try to evade, even to the point of self-harm.

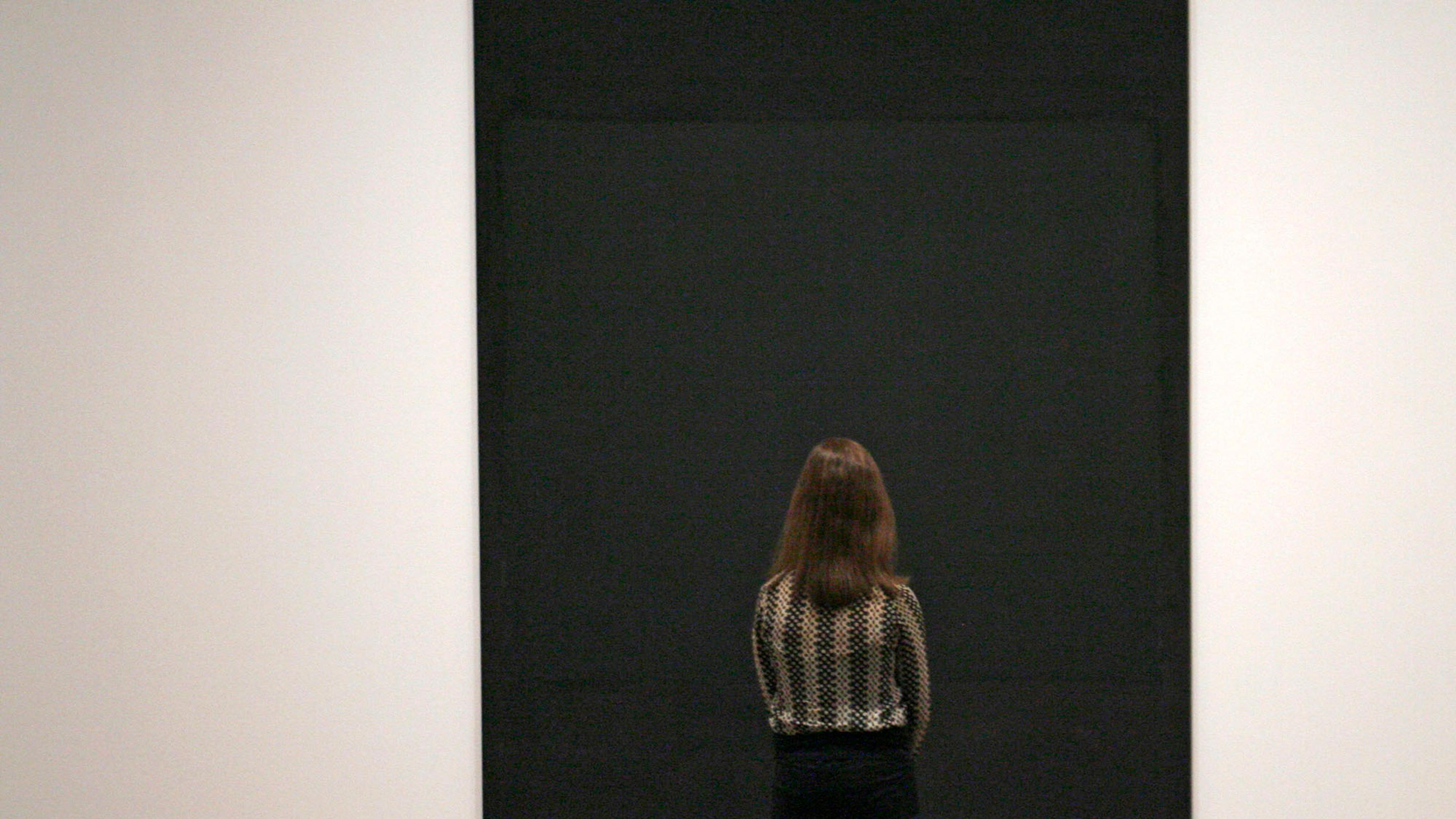

Artists with mental health problems have tried both to depict the experience of emptiness and to use their art as a way out of it. In Virginia Woolf’s essay ‘On Being Ill’ (1926), she offered this vivid depiction of emptiness: ‘We float with the sticks on the stream; helter-skelter with the dead leaves on the lawn, irresponsible and disinterested …’ In her suicide note to her husband, she wrote: ‘Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness.’ Mark Rothko, who also struggled with mental health problems and ended his own life, painted squares of colour that can be seen as depicting emptiness. In describing his approach in his essay ‘The Romantics Were Prompted’ (1948), Rothko said: ‘I do not believe that there was ever a question of being abstract or representational. It is really a matter of ending this silence and solitude, of breathing and stretching one’s arms again.’

A puzzling feature of emptiness is that people who report feeling empty also typically report feeling too full of feelings at times, and often go back and forth between the two extremes. Emptiness has historically been conceptualised as a symptom of borderline personality disorder (BPD), a relatively severe psychiatric diagnosis involving extreme anger, sadness and other emotions, impulsive behaviour and concerns about being abandoned. People with BPD are typically thought of as having too many feelings, too many thoughts, and behaving too rashly.

Why might the same person feel too empty and too full of feelings? The most likely answer lies in the concept of identity, or the internal sense a person has of who they are. Having a well-developed sense of self provides life with meaning, guides behaviour, and can be a psychological resource in times of distress. When a person has an unclear, disorganised and unstable sense of self – as is frequently the case for those diagnosed with BPD – they will have deep questions about what they should be doing and what should matter. Some people whose identity is not well integrated go back and forth between periods of emotionally intense efforts to figure out who they are and periods of numb emptiness.

My colleagues and I have spoken with hundreds of people, in our clinical work and research, about their experiences of emptiness. They have described feeling dead despite breathing, feeling as if they are missing something everyone else seems to have, having a hole where their heart should be, waiting for life to begin, not knowing what to live for, and not feeling a part of the world, among other vivid depictions of the experience.

Until recently, relatively little was known about emptiness; it was not typically studied as an important concept in its own right. However, two findings point to its significance. First, even among symptoms of BPD, emptiness stands out as a unique predictor of suicidal behaviour and treatment difficulties. What’s more, people who do not have a diagnosis of BPD can feel empty, too. For example, the experience is common among people with depression and schizophrenia diagnoses. Some individuals who do not have psychiatric diagnoses also struggle with emptiness. In one study, 10 per cent of college students reported feeling ‘chronically empty’.

Treatments focus on helping people become more aware of – and better connect – their thoughts, feelings and behaviours

The recognition that emptiness is important in these ways has led to a renewed interest among researchers. One question we have is whether emptiness is experienced largely the same way by everyone. In my work as a psychotherapist, I have had some clients who describe emptiness as a bodily sensation, as a kind of pit in the stomach or hole in the chest, and other clients who describe it more psychologically, as the absence of meaning or purpose. Are these different experiences of the same psychological phenomenon, or different phenomena altogether? My hunch is that these are two ways of experiencing a phenomenon that is difficult to express with words – but it’s something we need to explore further.

Another important question has to do with how the extremes of emptiness and emotional intensity work together. If they swing back and forth like a pendulum, it could be useful to know what makes them swing one way or the other, and what keeps the pendulum swinging. Perhaps understanding these kinds of patterns over time would help us better grasp why people feel empty, and how this leads to self-damaging behaviour.

There is little research focused specifically on the most effective ways to help people who feel empty. But several treatments have been developed for BPD, from different theoretical orientations, and research indicates that they are all about equally effective. While these treatments, including dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT), mentalisation-based therapy (MBT) and transference-focused psychotherapy (TFP), differ in certain respects, they have some key goals in common.

Each of these treatments focuses on helping people slow down in order to become more aware of – and to better connect – their thoughts, feelings and behaviours. For instance, in DBT, the therapist focuses on validating a client’s emotional experiences as a way to help them accept those feelings and make better choices about how to respond to them. In MBT, the therapist tries to help the client think about what is happening in the here and now, what they are thinking and feeling, and also what the person they are with is thinking and feeling. The goal is for the situation to begin to make sense, for the client to see that there are probably understandable reasons for feeling the way they do. And in TFP, the therapist focuses in particular on the relationship between client and therapist, but tries to help the client draw connections to other important relationships. This can help clients see how they bring negative experiences from the past into the present, better understand intense emotions, and become more willing to accept and work through difficult experiences like emptiness.

The hope is that over time, by learning to slow down these processes with the help of a therapist, people can better manage their feelings, reflect on where those feelings came from, and make reasoned decisions about how to respond to them. Each treatment approach emphasises the importance of doing this in a supportive, empathic and trusting therapeutic relationship.

I once had a client who attempted suicide with a firearm. When she woke up in the hospital, her first thought was that she was such a failure she couldn’t even end her own life. She expressed a profound lack of meaning in her life and, at times when this feeling became unbearable, she would go to the hospital. She would try all kinds of things to ‘get something inside’ herself, including eating, hurting herself and buying things she knew she didn’t need, but they didn’t seem to work.

In therapy, we talked about the part of herself that felt empty, and where she couldn’t find meaning, and tried to distinguish it from a part of her that was not empty, and where she could find meaning. To do this, she had to learn to lean into the experience rather than trying to avoid it. We used relaxation techniques to help her do this, and I tried to encourage her to experience the feeling of emptiness, without pushing her too hard. Over time, she began to describe how her relationship with me gave her meaning, and this helped her see that going to the hospital was a way for her to find the kinds of relationships that would ‘get something inside’.

After discovering that relationships were a way for her to find meaning and avoid emptiness, she saw a way forward. She adopted a pet. After some improvement, she volunteered as a ‘big sister’ mentor to children in need, and eventually she joined a social club where she made lasting friendships. Around that time, we ended our work together, confident that she knew what she could do during moments when she felt empty.

As psychologists continue to learn more about the experience of emptiness, the effort is likely to reveal important insights about how human emotions, identity and relationships are intertwined – and how to better help people who struggle with feeling empty, like my client, live more fulfilling lives.