What if bringing back home economics were a radical – not retrograde – act? And I’m not talking about a one-time course, introduced in middle school, when young people (deep into an adolescent surge of hormones) have already internalised gender norms dictating who should be mending socks at the kitchen table versus who should be welding metal in the garage.

Of course, we’d have to axe the name – a throwback to the 1950s, and redolent not just of gendered segregation but of heteronormative training and aspirational class-climbing. We’d also have to grade the offer if we’re to embrace teaching preschoolers to make tote bags out of dish towels and high-schoolers how to knit socks to the exact measurement of their feet. In short, I’m talking about establishing handcraft courses that are in regular rotation throughout the school year, just like music, art and physical education.

Through ‘handcraft’ courses, students learn by doing, making, drafting and constructing – the kind of manual work that has little need of specialised or costly equipment. Like the re-learning of a lost tongue, this is a form of reclamation clearly tied to the communal wellbeing of society, to stitching empathy and resilience to the shared knowledge and lineaments of a heritage.

In the United States, ‘Home Economics’ (or Home Ec) was officially transformed in 1994 and renamed as the gender-neutralised and capitalistic-shrouded ‘Family and Consumer Sciences’, under the national umbrella of the American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences. Depending on the school district, these courses can be required teaching in middle school, in topics ranging from sewing to babysitting, nutrition and smart shopping, to high-school electives in tailoring, interior design and prenatal development. Under the Family and Consumer Sciences category, the classes are broad and far-reaching, acting as primers in how to excel in ‘life management skills’ within a capitalistic system. Interestingly, their enrolments are in decline. Traditional Home Ec, meanwhile – the kind that still lingers in the national imagination, featuring a neatly dressed female teacher in her apron – faded due to a complicated calculus involving changing norms around ‘women’s work’ in the home, women’s entrance into the (paid) workforce, and the consciousness-raising work of feminism, combined with an increased focus on student test scores and college preparedness.

While there might be some overlap within the Family and Consumer Sciences catalogue, handcraft courses could offer an anti-capitalistic pivot, grounded in sustainability, self-reliance and skill sharing, rehabilitating what’s generally termed ‘the domestic arts’ within in an institutional setting. By institutionalising the instruction of handcraft, students can learn the rules and structures, and then break the rules, subverting them through an experimentation that is undergirded by knowledge of making. Such know-how is particularly useful when capitalistic societies come under strain, as an antidote to fast fashion, instant gratification and technological solutionism, and not least the drive for expediency – everything just a click away.

Its flaws aside, with the demise of Home Ec, it is clear that something very real was lost. The process of producing something by design, using simple tools to transform raw materials with logical and creative intent, is one of the most rewarding and fundamental experiences known to humankind. It is little wonder that during the COVID-19 lockdown, people in the US and elsewhere were sewing and baking en masse, bolstering their sense of self-reliance, thrift and cultural continuity at a time of profound economic upheaval – when kitchen conversations, boardroom deliberations and street protests addressed racial and public health disparities, while groping for a more equitable moral compass for the nation.

Still, the groundwork for reclaiming and requiring handcraft in an institutional setting is rooted not in this coronavirus catastrophe, but in another national calamity: the terrorist attacks on the US of 11 September 2001. Betsy Greer, a North Carolina-based writer and activist credited with coining the phrase ‘craftivism’, set the wheels in motion. In her Craftivist Manifesto, she wrote: ‘Craftivism is about creating wider conversations about uncomfortable social issues. A craftivist is anyone who uses their craft to help the greater good or in resistance to a greater societal ill.’ For Greer, in an immediately post-9/11 landscape, handcraft was personal, for it involved a slow process, made by hand rather than mass-produced, and with outcomes as distinct as the person who made it. But it was also political. Her embroidered political slogans and cross-stitched antiwar graffiti proclaimed: Here I am, behold what I can do and leave behind. Might institutionalising handcraft classes qualify as a craftivist act? To the extent that it is based in artisanal skills that capitalism devalues, and because its output is traditionally populated by women and passed down matrilineally, then perhaps the answer is yes.

The Craft Yarn Council, which has tracked trends in their industry since 1994, noted a surge in craft participation post-9/11. In 2002, the council’s first survey since the terrorist attacks found that ‘participation in these crafts increased more than 150 per cent in the 25-34 age category, jumping from 13 per cent to 33 per cent and representing 6.5 million.’ And, in 2004, yarn sales were described as ‘phenomenal, record-breaking’. People craft during times of catastrophe, and the current pandemic has taught us that they do so to combat anxiety, but also for the betterment of public health. Think of the numerous local community groups of home sewers making masks and hospital gowns for healthcare workers – sometimes using repurposed bedsheets. Or home-bakers delivering them food parcels. Everywhere saw shortages of elastic and yeast.

We – the public – now viscerally intuit that ‘domestic skills’ possess relevance and necessity beyond the home. Skills deemed run-of-the-mill as little as two generations ago – such as operating a sewing machine, planning and growing a garden, canning seasonal foods – now carry vital survivalist import. Plus, they are work that involves cognitive and physical labour – made all the more meaningful via generational knowledge transmission. What is produced by hand is linked to familial, public, mental and physical health, and a sense of purpose and self-sufficiency. Can’t get sliced bread? Then make it. No access to bleach or rubbing alcohol? Let’s clean with baking soda and vinegar. Let us husband disappearing dollars by darning old clothes and refashioning new ones from existing fabrics in our drawers. Home economics was basically a life hack, before ‘hack’ became a fashionable word for making lives easier in a capitalistic system that leaves people gasping for air.

The instruction of handcraft in school should be a slow process, to mirror the deliberate and measured process of making itself. More importantly, it should reveal an understanding of realities that are in many ways taken for granted but can be obtained only through the knotty action of making itself. Consider knitted socks. Every ‘sock student’ would learn a language corresponding to the anatomy of the foot. First comes the ‘heel flap’, which proceeds to ‘turning the heel’ – a series of short rows of stitching that couch the skinniest part of our foot (the backbone above our heel). Then there’s what’s known as the ‘gusset’, a triangular form that gives movement to the fabric between the ankle and the length of the foot. As an adult knitter myself, I had never given so much thought to the structure, measurement and functioning of feet until I began to make socks for them. It is thrilling to create a piece of fabric that fulfils the need of form and function for a physical structure that carries me throughout the day. It takes me a solid week to create a single sock, and, when life is busy, a month. Sock knitting is an act of self-assertion, of awe, of colour worship, of anatomical knowing through making: a declaration of self-worth and pride in one’s work.

What we make, we know. This is visceral. And what we know influences our values, frameworks and economies. Philosophers since Plato have argued that the physical construction of fabric – for instance – affects the scaffolding of knowledge-building, as well as our actual built environments. ‘There is a distinct ontological dimension to making,’ writes the cultural theorist Ulrich Lehmann, who teaches design at the New School in New York City, ‘as it implies the emergence of the new, of something that is whole, from separate, often disjunctive and opposing components.’ What’s more, what begins in the home or classroom expands beyond familiar borders to fundamentally reshape norms around gender, capitalism, sustainability and nationalism.

Plato pulled upon craft, specifically the art of weaving, in his Dialogues, as a metaphor for the nature of being and the production of knowledge, perhaps because the weaving process offers as fine a metaphor as any for the construction of a ‘social fabric’ and moving parts to a whole. In fact, Plato compared a woven fabric to the state and its citizens. Just as warp and weft threads differ and serve connected but distinct purposes in a piece of fabric, this reflects how citizens differ from each other and those differences can serve the state in ‘deep and important ways’.

Handcraft classes in schools might potentially mesh the practical with the philosophical: the knowledge of making with its civic applications – which is a matter not just of material output but of values. This is especially apparent in considering how and why people bring their handcraft into the public sphere (such as face coverings and masks) as a solution to a social ill, in the form of a sale, gift, barter or an act of community beneficence. With making, creators live in the moment, and have – as David Gauntlett, a media theorist at Ryerson University in Toronto, writes – ‘the sense of being alive within the process; and the engagement with ideas, learning and knowledge which come not before or after but within the practice of making.’

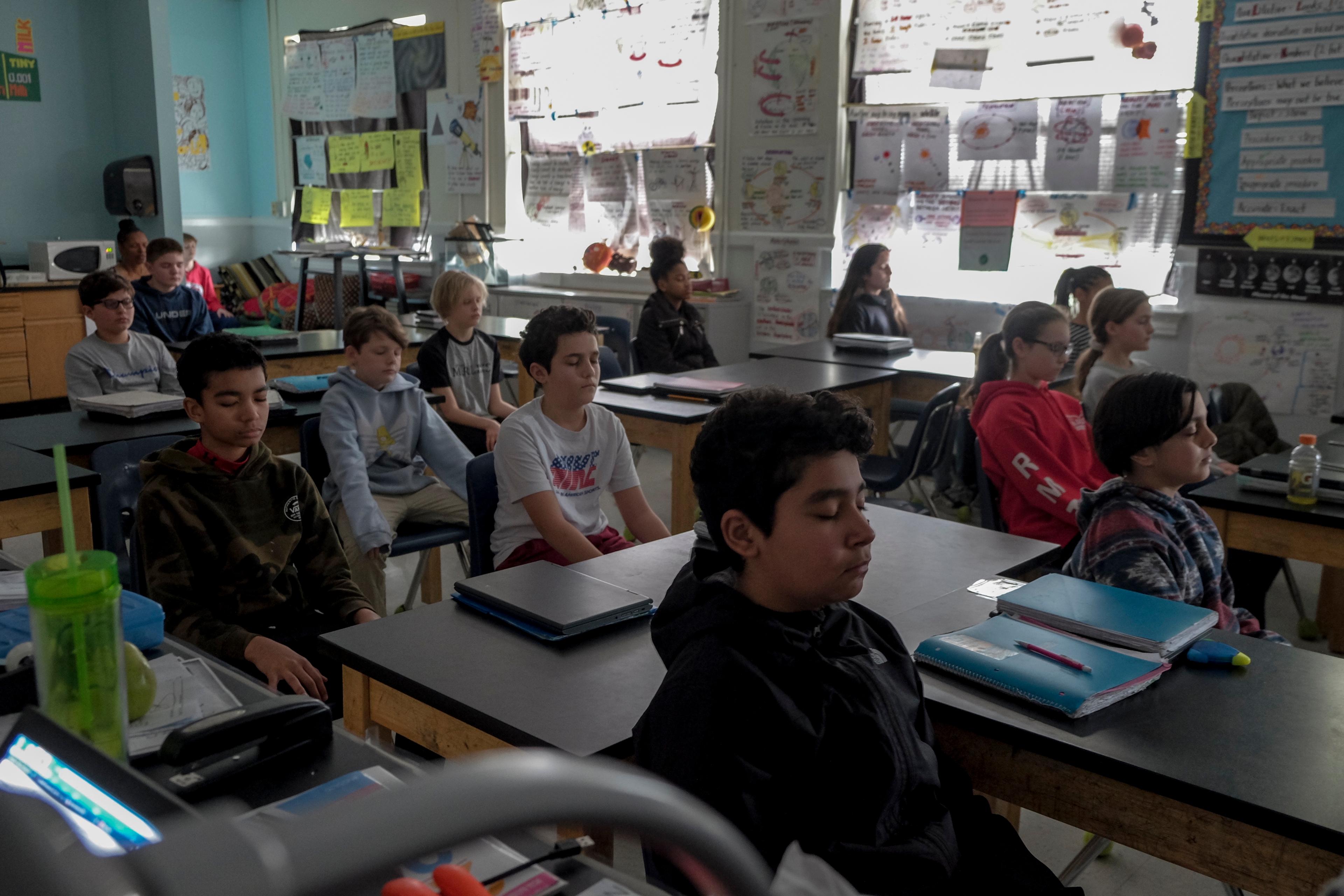

With students likely to return to the classroom in a drastically altered schoolscape, now is the time to reconfigure the pathways to knowledge and knowing. Let mandatory handcraft courses help knit together a new route towards sustainability, equity, health and civic engagement in a post-pandemic world. At the same time, they can offer an antidote to our purchase-driven, 24/7 culture, bringing joy, calm and flow into formalised school settings a few times a week – what the educator Ellen Dissanayake calls ‘joie de faire’.

In the classroom, students can be introduced to handwork for the practical solutions it offers. Outside of the classroom, it can be part of a broader response to social, physical and economic problems, and the very real conundrum of being human. Handcrafts are a pathway to creating the most meaningful existence I know how to live. Democratising handcraft knowledge and the accessibility of tools needed for its creation is a radical enterprise: teach them young, and mending and making can be elevated as the cornerstone to a life well lived – whether out of scrappy necessity or personal choice. Either way, mandated handcraft courses offer an uplifting return to a symbolic US, where the interplay between imagination and invention are the basic ingredients for a more equitable launchpad for our younger learners.