The Western philosophical tradition has taught us to think of ourselves as essentially indoors. We each inhabit a separate box of consciousness – imagine a cave, a castle tower or a room – over which we rule and in which we store up perceptions, feelings, thoughts and memories. On occasion, we venture out to acquire more of these. We creep out of our lonely interior realm and into the wider world, beholding things and bumping into other people, before retreating with our booty into the self-contained container of the self. There we reign, solitary and supreme.

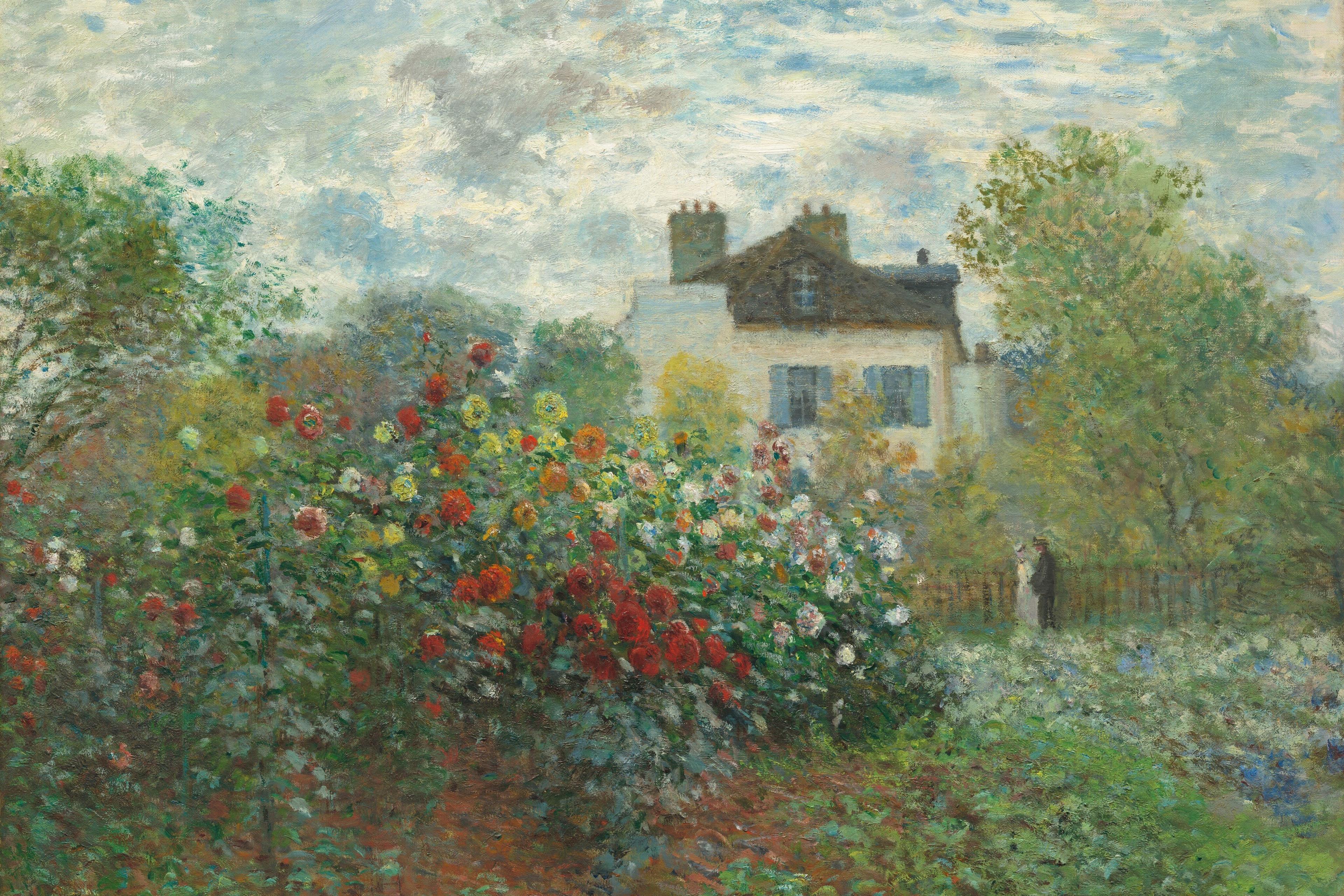

The German philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) rocked philosophy by thinking of us differently. As Jean Wahl once put it, for Heidegger we are ‘always essentially outdoors’. Again, imagine this as you will: human life played out on a pleasant garden patio in the summer, with lemonade and card games, or as a grand cross-country quest, filled with adventures undertaken and hardships suffered. Either way, the human being is not solitary and self-contained but out and about in the midst of things, in the company of other people, mixed up with what there is – and so, as it were, at the mercy of the elements and weathering the vagaries of the world.

Thinking of us as essentially outdoors challenges us to grasp ourselves in a new way: as entangled and vulnerable. There are reasons that we resist seeing ourselves in this way. But there are also benefits to doing so – benefits to acknowledging that we are, as Heidegger puts it, ‘being-in-the-world’.

Being-in-the-world is our distinctive way of being. This might seem like an odd claim. Isn’t everything in the world? ‘World’ is usually what we call the place where all the stuff is located. But we are not located in the world in the way that the lemonade is in the pitcher, the pitcher is on the patio, or the backpack is on the quest. We are on the quest, on the patio, and so in the world distinctively: we inhabit it as that in and through which our lives take place and make sense. The world is not a container but the meaningful context in which we dwell. We are in the world in the way that someone is in love or in business.

To be outdoors in the world is to dwell in a rich, meaningful context, along with other people

If you are in business, you are immersed in the world of business-meanings and business-matterings. You take up business-projects, present yourself in a business-like manner, and care about business-things. Similarly if you are on a quest: the quest is your life-defining project and whatever you encounter is meaningful as helping or hindering your journey. But projects need not be life-defining in order to situate us in a meaningful context. Notice how taking up the project of playing cards charges some of the things around us with powerful significance. The equipment that we need in order to play lights up; certain options for acting entice us (good play!) and others are now out of the question (that’s cheating!); our companions polarise into teammates and competitors. We ourselves become intelligible as skilful shufflers, good bluffers or sore losers. Everything is suffused with significance. In all areas of our lives, big and small, we take up projects and immerse ourselves in the world of meanings and matterings that is thereby opened up.

To be outdoors in the world is to dwell in such a rich, meaningful context, along with other people and the paraphernalia of our lives. It is to be already engaged in life projects and amidst meaningful things – not to be storing up perceptions of objects inside an isolated cave.

By dwelling in the world and taking up projects, we make things meaningful. The flipside of things being meaningful is that we depend on them. When I propose a card game on the patio, the paraphernalia of the game becomes significant; but if I am to play cards, I need that equipment to be available and in good working order. I cannot carry out my project if the equipment is missing or inadequate, or if the conditions ‘on the ground’ do not permit it. Being out and about in the world involves depending on things that are not up to us. That dependence makes us vulnerable.

Our destiny is bound up with the destiny of other things and other people

If half of the cards are missing, we cannot play card games. We do not get to be skilful shufflers or good bluffers – at least for the moment. If the strap on my backpack breaks or if the terrain is impassable, my attempt to carry out my quest will be thwarted. My project is undermined. How disruptive this is depends on the degree to which the project is life-defining, and so on the extent to which we spend our lives out and about in that particular world. If a thunderstorm means that we cannot play poker on the patio, that is a minor and temporary disruption. But if I am a professional poker player and gambling is outlawed, I have to give up my entire way of being-in-the-world.

Living outdoors and in the world means depending on other things and other people in order to be who we are and to do what we do. This dependence puts us at risk. We are vulnerable to being impeded or disrupted by the paraphernalia of our lives, if it is not there or is not what we need it to be. This belongs to what Heidegger calls our ‘facticity’: our destiny is bound up with the destiny of other things and other people. Earlier I put this metaphorically by saying that we are at the mercy of the elements and must weather the vagaries of the world.

To live essentially outdoors is, as it were, always to be subject to the weather. And it is the risk of bad weather that drives us indoors. It is in order to deny our facticity and its associated vulnerability that we want to think of ourselves as indoors. A sovereign, self-enclosed substance is not tied to the destiny of anything else. It does not depend on anything in order to be but exists all by itself. Thinking of ourselves in this way is a self-protective strategy. It purports to make us invulnerable: Deus Invictus, God invincible and unbound.

According to Aristotle, fear motivated the earliest philosophers to seek regularity in the natural world. According to Heidegger, anxiety about our finitude and vulnerability motivates us to imagine ourselves as self-enclosed substances. It started with René Descartes (1596-1650), who systematically tested all his knowledge in search of absolute certainty. He found that the only things that he could not doubt were the existence of God and that he himself thinks and so exists (cogito, ergo sum). The ‘self’ whose existence is impervious to doubt is ‘a thing that thinks’, not a thing that laughs or plays cards. It is a secure ‘interior’ in contrast to a doubtful ‘exterior’ world. From this external world, the self can withdraw all engagement so as to deal only with that which is absolutely assured, absolutely interior. Nothing could ever happen to shake such a thinking thing – which is precisely the point.

If we truly were rocks or islands, nothing would move us to care, either positively or negatively

The Cartesian view of the self has been baked into much of Western philosophy, and so into the natural, social and human sciences, as well as into many cultures’ common sense. Many of us operate unawares within this ‘natural’ view, although some take it on more explicitly and take it further, actively trying to deny or suppress human vulnerability. They might reject our dependence on our natural environment, fantasising about life on Mars and ignoring the climate crisis, or they might pretend to be absolved of having to care about other people and things, transcending empathy into selfish solipsism. For such people, the fantasy of invulnerability helps them to feel strong and powerful.

It is an appealing fantasy. But it is nonetheless a fantasy. And it comes at the cost of denying our very real entanglement in things. We are not and cannot be Deus Invictus but must be – if I may put it this way – Homo Implexus, the human being entwined and entangled. The truth is that we are vulnerable beings who live outdoors, amidst other things and at stake in them. To pretend otherwise is to deny the sober truth of your essential finitude as being-in-the-world.

It is also to shut yourself off from being immersed in things that matter – or, at least, to try to. This is a pretence that makes your life worse, since it leads to painful isolation. As Simon and Garfunkel sang, the pretence that ‘I am a rock, I am an island’ means that ‘I touch no one and no one touches me’. The point is not about physical touch but about being touched in the broader sense of being moved and affected. If we truly were rocks or islands, nothing would move us to care, either positively or negatively. We would be cut off from others, unable to celebrate their successes or commiserate with them about our losses, unable to love them or hate them – or even to be indifferent to them. They could not move us at all. So too for things: we would be cut off from enjoying the sunshine, savouring the lemonade, and being frustrated by impassable terrain. We can be moved by things only if they matter and are meaningful, and for that they must be entangled in our projects.

So, if we try to pretend that we dwell indoors, we may win a faux feeling of invincibility. But we lose something more important: our openness to being moved. As Franz Kafka put it: ‘You can withhold yourself from the sufferings of the world; … but perhaps this very act of withholding is the only suffering you might be able to avoid.’

We can now see how being-in-the-world is like being in love. Not only is being in love a way of inhabiting a context of meaning, it is a way of allowing my life to become entangled in what is not up to me. In loving, I risk myself: I put the success of my projects and my happiness in the hands of someone else. But even though it makes us vulnerable, loving in this way is worthwhile because it makes for a flourishing human life. It makes our lives bigger and more beautiful. It does so precisely because it gets us more outdoors. Not doing that – trying to confine ourselves indoors – makes our lives smaller and pettier. It also makes us less truthful, less authentic.

Heidegger calls on us to see ourselves as we are: to accept our dependence and vulnerability, to recognise our humanity as entwined and entangled, and so to acknowledge our being as being-in-the-world. The call is, in part, to those who try to be Deus Invictus rather than Homo Implexus; they must recognise their error and its dangers. But it is also a call to all of us to notice what we take for granted about what we are like, in the ways that we speak and think every day. And it is, finally, a call to philosophers to take up the task of developing a strong alternative to the vision of the self trapped inside. Heidegger opened the door to thinking of us differently, and in doing so he set philosophy off on a path that it is only starting to follow. What would it be to clear-sightedly see ourselves as outdoors? What new concepts, new vocabulary, new intuitions would we need to develop? Even as philosophers and others adopt the vocabulary of ‘being-in-the-world’, there is work yet to be done. This is the work of coming to meet ourselves where we already are: out in the world, on the grand adventure or summer afternoon of our lives, dwelling always essentially outdoors.