‘Would you like some?’ says the child, shaking the red chocolate box to elicit the telltale sound of the treat. Quivering with glee, he watches as his little sister excitedly accepts the gift and opens the box… only to find that the usual contents have been replaced with marbles. The older child giggles uncontrollably. The trick is complete.

But how did the older child know the trick would work? Playing a trick like this required him to have a sense of what his sister would be thinking, given the context. His words to her, the recognisable container and the familiar rattle were all cues to make her think she was being offered a real treat. Only when his little sister opened the box, he understood, would she know what was clear to him.

It’s not until the age of four or five that children develop this flexible ‘theory of mind’: the ability to reason about others’ thoughts and feelings. This includes understanding that people’s beliefs can be decoupled from reality (sometimes to comic effect). This ability to ‘read’ other people’s minds is crucial for social interaction. Which direction is that car going to turn? The indicator lets you infer the driver’s intention. Does that attractive acquaintance like you? Their eye contact and flick of the hair might give you a sign. Are we communicating about this topic well? To answer that question, we have to imagine what the reader will need to know in order to follow our train of thought.

Theory of mind has been a topic of intense study since the 1980s, when psychologists first developed ‘false belief’ tasks. These tasks involve asking children to reason about other people’s behaviour in scenarios where those people don’t have full information. For example, Mum leaves her car keys on the kitchen table; when she is gone, Dad puts the car keys in his pocket. Mum comes back to the kitchen – where will she look for her keys? Children under the age of four predict that Mum will look in Dad’s pocket; after all, that’s where the keys are. However, older children understand that Mum will expect the keys to be on the table, and that Dad might be in trouble.

An enduring question, one for which we and other scientists are still seeking answers, is what happens around that age to make this critical ability possible. How, exactly, do we become ‘mind readers’?

Historically, there are two big ideas about how theory of mind works. ‘Simulation theory’ suggests that we routinely read other people’s minds by imagining how we would think and feel in their shoes. So, by this account, you might ask yourself: ‘What would I think if I saw this chocolate box and heard it rattle?’ – and if you can correctly work through your own imagined thought processes, you can arrive at what someone else would think.

By contrast, some psychologists and philosophers have taken the ‘theory’ part of ‘theory of mind’ literally. They argue that people have something genuinely like a scientific theory of others’ minds, which can be understood using theoretical terms like ‘if X, and if Y, then Z’. A concrete example might be: if someone wants X (eg, chocolate), and thinks Y (there is chocolate in this box), then they will do Z (open the box expectantly).

As adults, people may use a mixture of these strategies to understand others’ minds – sometimes ‘simulating’ how they would feel or what they would think in another person’s position, and sometimes appealing to what they know about typical behavioural patterns.

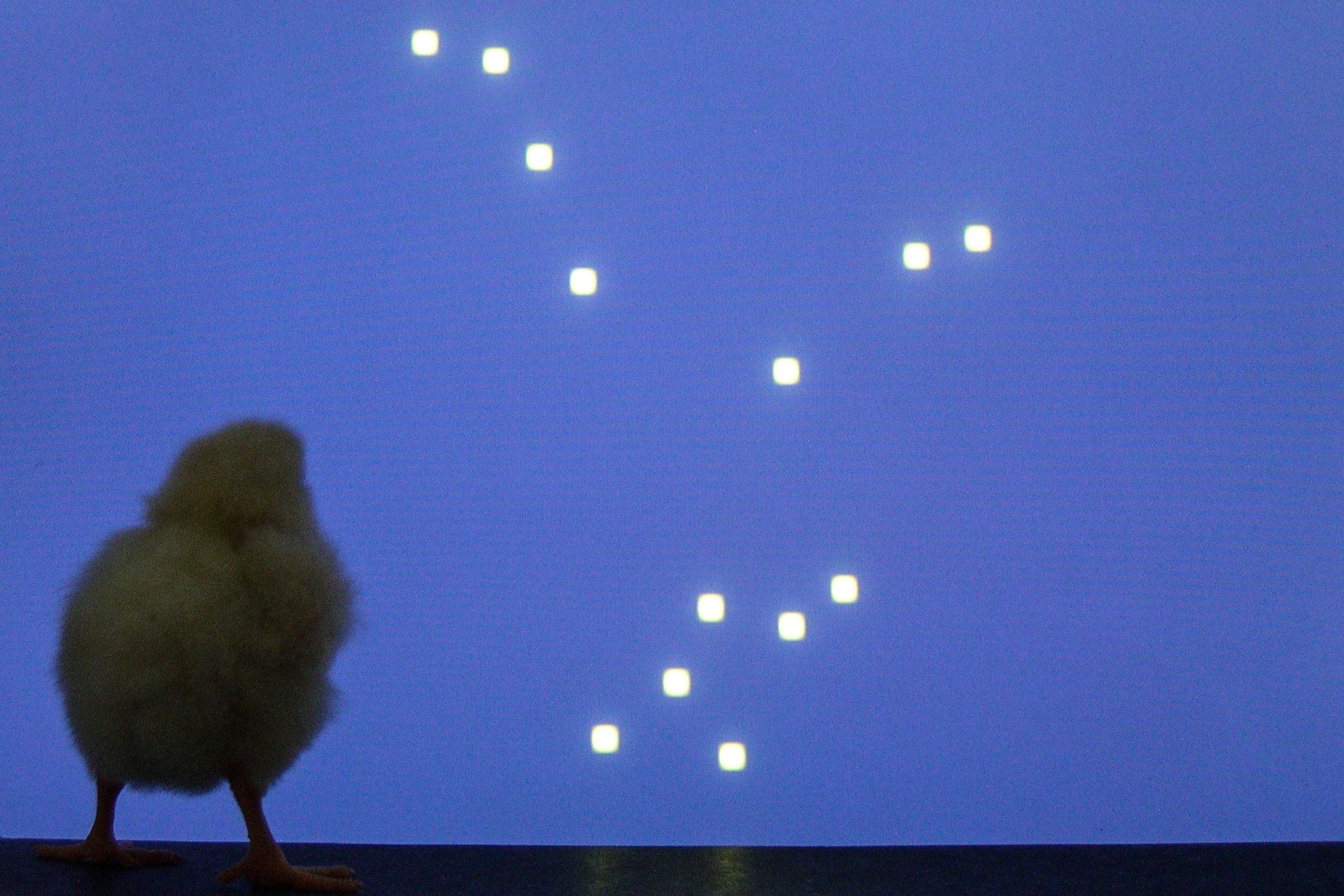

Young children are typically considered to be egocentric, a trait that abates with age

In a recent research project, we used the intuitions behind both of these theories to try to uncover the developmental building blocks of theory of mind. As with adults, when a child thinks about what someone else is thinking, they might sometimes imagine how they would think or feel in another’s position, and other times they might instead draw from their knowledge of what others usually do (eg, ‘people look for things where they expect to find them’). However, to grasp that another person can hold a false belief, we hypothesised, a child would first need to have an idea of what a belief, or thought, is. Thus, a child’s ability to introspect about their own thoughts – also known as metacognition – could be a developmental building block for the ability to reason about the mental states of others.

That, in itself, might not be enough. We also expected that self-control, which children take time to develop, would be important to the ability to ‘read’ others’ minds. In order to guess what’s happening in someone else’s mind, one has to be able to temporarily put aside one’s own experience of reality, which requires inhibition. This is why young children are typically considered to be egocentric (think of the ‘terrible twos’), a trait that abates with age.

Past research has suggested that the first signs of metacognition – for example, reporting feelings of uncertainty – emerge at the end of toddlerhood, around the same time as the first signs of self-control and theory of mind. We wanted to take a closer look at the order in which these skills emerge, to see if what we found would support our hypothesis: that metacognition and self-control are necessary for the development of theory of mind.

We saw a group of Scottish children three times, over a year and a half, starting when they were three to four years old. Each time, we gave them the same set of assessments, allowing us to see when metacognition, self-control and theory of mind emerged in the same children, and how they related to each other. To examine children’s metacognitive abilities, we asked them to pick out an item (say, a duck) from a pair of blurred pictures, and then asked whether they were ‘sure’ or ‘not so sure’ of their answer. If children tend to say ‘sure’ more often when they’ve got the answer right, it’s a sign that they are sensitive to their own certainty. Our measures of self-control included a version of the popular game Simon Says, in which children were to follow certain instructions but not others. To measure theory of mind, we tested children’s understanding of beliefs, knowledge, intentions and emotions – seeing, for instance, if they could correctly say whether a character knew the contents of a container.

Across this developmental period, we found that the majority of children first became competent in metacognition, followed by self-control, and then theory of mind. Our results imply that the first two abilities might provide important stepping stones to the ability to reason about other people’s thoughts and feelings. Further, metacognition and self-control were related to each other across time, suggesting that being able to introspect about one’s own thoughts plays a role in the development of self-control.

For many of us, then, getting to know our own mental states early in life may be key to other skills. Let’s revisit the chocolate trick: the big brother knows that there are marbles in the chocolate box. However, he has to suppress this knowledge to focus on what his sister will think. He might plan the trick by considering what he would think in his little sister’s shoes, or by predicting an action pattern (people who want chocolates look in chocolate boxes). But, in either case, he must already understand that thoughts – not reality – guide people’s behaviour. The simplest way for a child to arrive at that understanding might be through introspection.

Insights into how theory of mind emerges are important from a practical perspective. The development of this ability to reason about other minds can be disrupted by environmental factors, such as a lack of opportunity for social interaction and language development, and by neurodivergence, which is sometimes associated with difficulty in social reasoning. To support children in developing theory of mind, experts might usefully target its developmental building blocks. That could include focusing, in part, on supporting a child’s self-reflection and self-control. For example, while some researchers have sought to help children develop theory of mind with the aid of thought bubbles that illustrate story characters’ thoughts and beliefs, a more accessible starting point for many children might be encouraging them to engage in introspection – perhaps by externalising their own thought processes in this concrete way (eg, within bubbles).

However, it is crucial to consider whether the developmental foundations of this skill set are universal. Researchers are currently pulling together to address a pervasive cultural bias in developmental psychology: the majority of information we have on child development is based on studies with Western populations. In Western societies, people tend to consider a principal goal of child development to be gaining independence and self-reliance – becoming the ‘main character’ in one’s own life. But, in much of the world, a principal goal is to support a child to be interdependent, to fit in with their social surroundings to sustain the greater good. For example, in Japan, developing omoiyari – a concept similar to empathy and sympathy – is a key goal of child-rearing.

There could be significant cultural differences in the stepping stones to theory of mind

Perhaps surprisingly, given this social focus, research suggests that children growing up in ‘interdependent’ societies tend to develop these abilities differently, demonstrating self-control earlier but theory of mind later than their Western counterparts. This apparent difference could be because standard theory of mind tasks have been developed using a Western lens, focusing on an individual’s intent as the key driver of behaviour. However, it could also be due to substantial cross-cultural variation in the way people mentally represent self and other.

Findings from developmental research, including other work we’ve done, indicate that there could be significant cultural differences in the stepping stones to theory of mind. In this research, we asked children in Scotland and Japan to complete the tasks described previously. In both groups, we again found that introspective ability was related to self-control. However, neither ability was strongly related to Japanese children’s theory of mind, suggesting that the developmental precursors may differ between independent and interdependent societies.

If this cross-cultural finding holds in future research, how might we explain the difference? It is possible that in interdependent societies, it does not take (as much) self-reflection or self-control to be able to consider another person’s thoughts and feelings, since other people’s perspectives are always closer to the forefront of thought. In cultures with an interdependent focus, children may follow a different set of developmental stepping stones to theory of mind, perhaps through the scaffolding of shared perspectives of reality. In other contexts, however – including in the independence-focused West – a child’s ability to guess at other people’s thoughts and feelings is likely to begin with introspection on their own.