Ever since my husband (M) moved to Germany to pursue his master’s late in 2022, we’d been living apart on two continents. The summer following, I got a chance to spend two months with him in his rented apartment in Frankfurt. With its insulated glass doors, automated windows and extremely organised interiors, the apartment was shut off from the outside world. If you rolled down the shutters, you could easily forget if it was day or night. Everything we needed was indoors. If M’s room didn’t come with a balcony attached, it would have also been easy to forget that there was a world outside, too.

This mode of living was so unlike what I was used to in Delhi that my stay with M created a subliminal shift: it forced me to consider life and its cadences, and their direct dependence on the spaces we call home.

Back in Delhi, I was renting a two-bedroom ground-floor flat that came with two (tiny) balconies, a large living room and a dining space attached to the kitchen. The neighbourhood cats were always dipping in and out of the place, reminding me that mine was a porous and accepting way of living. Such a fluid arrangement of space suited me. Cats, people and seasons could come and go but I was the constant, unmoving, governing factor. Head of the household. I’d decide when to leave the balcony doors open, when to invite people over, when to step out. In the backyard, there are unending views of trees and the constant cacophony that comes with living in a bustling and bruised city like Delhi. Next door is a massive secondary high school where hundreds of children screech in the playground every morning. I hear them singing during assembly, and the music of their carnival practice and performances is the background to my days. When my upstairs neighbours prepare their Bengali dishes at weekends, my entire house is pervaded with the mouth-watering aromas of mustard and fish. Their kids drop by sometimes, in the evenings, to take Hindi language lessons from me or just to say hello to the cats. This carousel of tangible human activity makes up the interiors of my day-to-day life. In a sense, it is a tactile existence, requiring more from me than is immediately apparent.

In Delhi, it’s almost impossible to be self-involved, for a boundaryless living arrangement invariably pulls me into other people’s worlds; that of Raju, the door-to-door vegetable vendor; the grocer who home-delivers past business hours; the stray cats who come to visit and sometimes stay. My local chemist, the house help, my upstairs neighbours, the society guard – all constitute my daily living as much as I do, making me a more social, dependent, interactive person. This kind of constant exchange with the outside world alters the very fabric of an individual.

M’s Frankfurt flat has dedicated rooms for different people from different parts of the world. There’s a shared kitchen and hall area and a massive balcony intended for everyone’s use, but it ended up coming in handy only for me. Over last year’s extended summer, the endless stretch of that balcony became my island of comfort. I took work calls as I paced its length, the blue sky stretching above, allowing for a kind of shelter from all that was unknown: a new organisation, new colleagues, new projects to get lost in. The German sun worked like a balm, soothing my anxious nerves as I spoke at length about ongoing projects. Up in the air, in a sterile, muted space, cordoned off from the world below, the balcony became an oddly private space. A space like this in Delhi would be a window through which the outer world – the turgid air, the noisy monkeys, the neighbour’s drying laundry – would seep in. But the Frankfurt balcony gave me space to be by myself, suspended between a self neither fully here nor there.

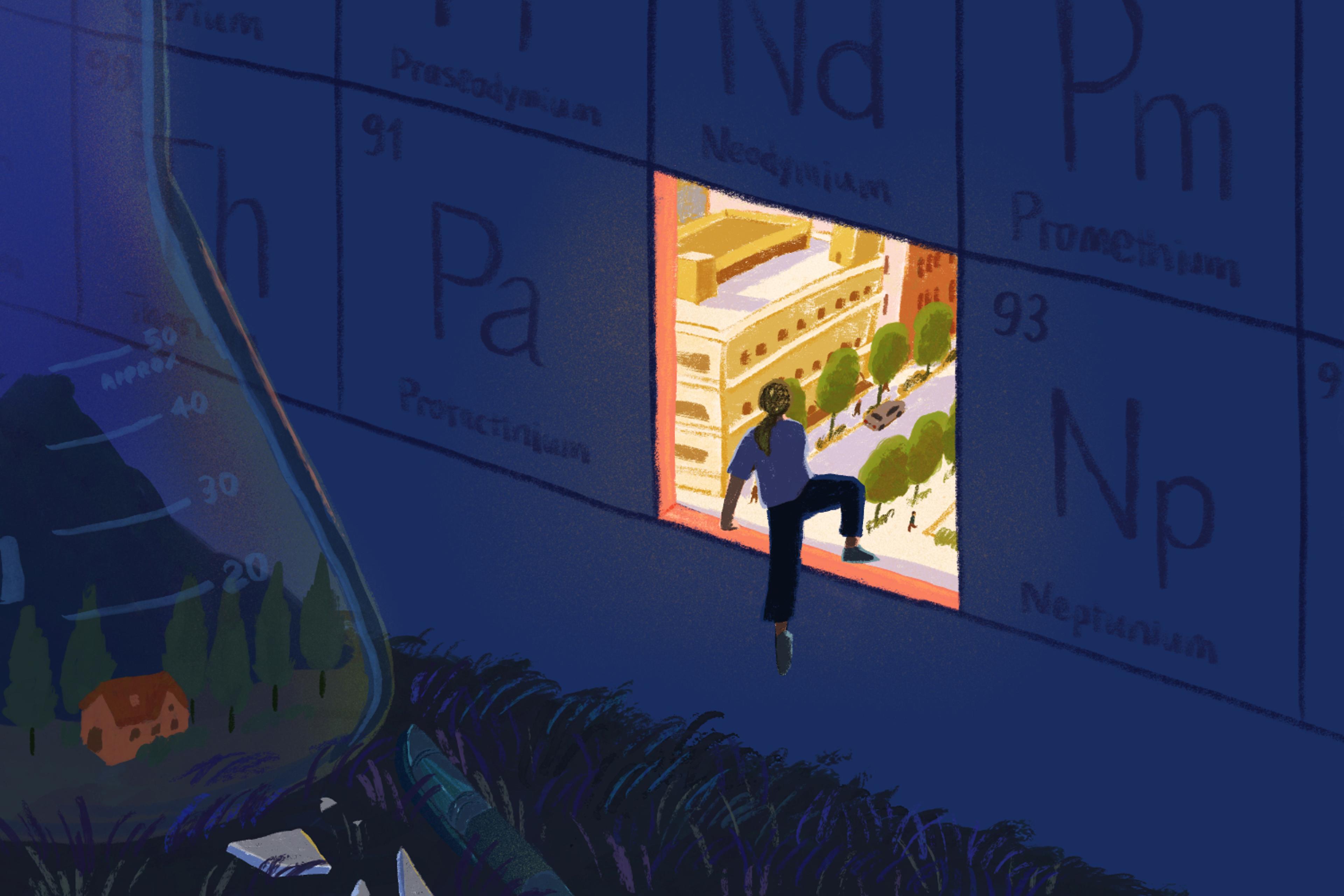

I spoke some German. Broken bits remembered from university days spliced with new ones from Duolingo. I spoke haltingly, afraid I might cause irritation in others. I would switch to English whenever I could. Why had I not bothered to learn German better before setting foot in Frankfurt? Had I done so, I reflected, it would have hit even harder that I was, in fact, on alien land. This reminded me of the quandary that the novelist Jhumpa Lahiri was faced with when she was in Italy, trying to converse in Italian: ‘I was more interested in the how than the why: how to speak the language better, how to make it my own.’ But living in the air, on the fourth floor, I hardly ever engaged with my neighbours. Instead, I was always moving in and out of the apartment, negotiating the city, with its splendid roads and German grocery stores. Like Lahiri, I was trying on a new persona in a foreign land. Ambling by the Main river, I could be anyone. And in many ways, I was. At such a remove from all I had known before, this was as good as a new life.

With this new way of living came anonymity, privacy, and the fantasy of exploring options I might not have in Delhi

I could wake up whenever I wanted. In the 45 days I lived in M’s Frankfurt apartment, the doorbell rang fewer than five times. There was a special, almost eerie kind of quiet that enveloped me, and that I filled in by listening to a mix of Bengali and English music. I would wake up, prepare my breakfast making as little noise as possible so as not to disturb the other people in the apartment. These beats affected my mood. The excessive quiet, the over-reliance on my own self, the individualistic way of looking at things accumulated, became a kind of narrow optic through which I observed life in a more limited way.

In Frankfurt, I felt freer than I’d felt in Delhi, but also a lot more self-involved. It was as if I had to put on borrowed clothes, or something akin to trying on various sizes and colours in a store changing room. I was yet to know what would fit me best. With this new way of living came anonymity, privacy, and the fantasy of exploring options I might not have in Delhi. In M’s Frankfurt flat, I could be my own person, minding my business, cooking meals alone, cleaning up after myself. My days represented an atomised, solitary journey. Such a contrast to my life in Delhi, where there were conversations I needed to have on a regular basis, however much I didn’t want to; people I had to socialise with no matter what my mental space or mood might be. In effect, I’d stumbled on the perfect marriage of isolation and first-world living. There were days when even a one-off conversation with a stranger was hard to come by. It fed the solitude-seeker in me, who’d look askance at the city’s visage during her walks, AirPods in place, listening to a podcast, using the time to ruminate inwardly. That there was no impingement from the outside world meant I could immerse myself fully in my work, or the book I was reading, or the essay I was writing. Some mornings, I’d get coffee from the Wiener Feinbäcker next door, and sit there with a cold ham sandwich, writing my morning pages on my phone’s Notes app.

Living this way made me realise how much I could preserve, engage more with my own thoughts, and nurture a healthy relationship with myself. There were flatmates I might have made friends with, or at least opened up to more, but something held me back. There was a language I could have learned better (and maybe I will in future) but I didn’t want to rush into that either. I wanted things to take their own sweet time. I wanted them to unfold in organic ways. It dawned on me then that I held myself back because I was ready to leave Frankfurt sooner rather than later – and if I was not to stay, why should I even bother? While I yearned to establish an emotional connection – with a person, or the German language or any aspect of German culture – I also took stock of the vanity of such an attempt. I would be leaving in a few weeks, after all. Therein lay the inherent migrant’s dilemma of how much to blend in, when to desist, and how to pluck oneself away because there is the chance of feeling deracinated.

Back in Delhi, I had to readjust to wake early in the morning, with the milkman ringing the doorbell and leaving a bottle of milk at my doorstep. Then came the garbage collector and, soon after, daily vendors poured in, hollering their sounds on the roads, calling out for vegetables or fruits, ringing my doorbell in case I might be looking for something. I was reminded of the kind of living advocated both by the urbanist scholar Jane Jacobs and the filmmaker Agnès Varda. According to Jacobs, neighbourhoods with their communities of residents and bustling pavements make for an ‘intricate sidewalk ballet’. Her vision of the city chimes with my version of Delhi. The most revealing aspect of Jacobs’s work, which resonates deeply with me, is her emphasis on knowing our cities, through our neighbourhoods and the people who populate them, in such a way that we can map them internally. In Dark Age Ahead (2004), Jacobs writes: ‘A community is a complex organism with complicated resources that grow gradually and organically.’

I encountered Varda through her documentary Daguerréotypes (1975), a time capsule of working life in the Rue Daguerre in Paris. Through Varda’s lens, the businesses and their owners are the lifeblood of the neighbourhood – bakers, tailors, butchers, drivers, perfumers, music-store staff – creating an intrinsic mesh of everyday life. The sociological fibre of the film felt deeply familiar to me in closely resembling my way of life in Delhi and in capturing what it’s like to be, even fleetingly, part of a revolving cast of a densely matrixed locale, everyone a participant in the daily dance of life. Varda jumped out at me as a poet for whom place was the muse (for her, it was France). I later discovered that she’d described this film as ‘more or less a casual look at my neighbours’ – ranging within a 90-metre radius, too, because that’s how far the electrical cables of her equipment stretched from her own apartment.

In the absence of an immediate circle to depend on, my approach to life there felt restless

Varda’s films are so deeply rooted in the cultures, milieux and neighbourhoods of their time. She has created, through her vast repertoire, an imagery about how people, places, buildings share memories. Varda’s films exude a subtle sense of poetry, which has helped me mine them for meaning about my own surroundings and to think about different ways of placemaking; of making the invisible visible and, in seeing the unseen, to know and learn from the city while simultaneously living in it.

Admittedly, a good part of my hours in both places was spent in a kind of a limbo; waiting for the days to end, for work to start (or finish): for life to happen. In Delhi, I work during the day, then figure some route through the lonesome nights. Friends visit me, we cook together, drink, dance, go out and talk. In Frankfurt too, I spent the majority of my days working alone, but the nights were golden when M returned. Still, in the absence of an immediate circle to depend on, my approach to life there felt restless. Behind this shift, I sensed the chaff of differing social codes. Germany, and by extension, Western society, is built on individuals seeking to better their lives in their own singular ways, whereas the Indian middle-class life is rooted in a more communal style of living. It makes the experience of life in India more like a palimpsest, something that keeps folding in on itself, revealing within an intricate mesh of interdependent systems and individuals that coalesce to create a whole.

All this is not to say that I preferred one way of living to the other: I’d made my life in Delhi from scratch, too. But I learnt that, wherever we go, we change as individuals; my memories of my time in Frankfurt are very much governed by the interiors of the flat I lived in, whereas my memories of home, where my heart lives, are boundless – even if I can sometimes feel like a tourist there, observing the very life I’ve woven myself into. Still, I wonder if our psychology alters in accordance with the physical living spaces we inhabit – if ‘where’ I live makes me the person I am? Like James Baldwin in Giovanni’s Room (1956), I wonder whether ‘Perhaps home is not a place but simply an irrevocable condition.’