Anxiety is a signal that danger is imminent. When the danger is real, anxiety can help to keep us safe. The problem is that for many people, anxiety becomes a false alarm – and it can lead someone to feel just as threatened as if there were real danger ahead. Most of us are familiar with the physical sensations of anxiety, such as a rapid heartbeat or a sinking feeling in the stomach, and the mental symptoms such as racing and worrisome thoughts. In terms of behaviour, avoidance is the hallmark symptom of anxiety. Simply put, we avoid what we feel anxious about: if we are afraid of heights or snakes, we avoid skyscrapers or walking in tall grass. People who experience social anxiety often avoid social gatherings or situations where they might have to speak in front of people.

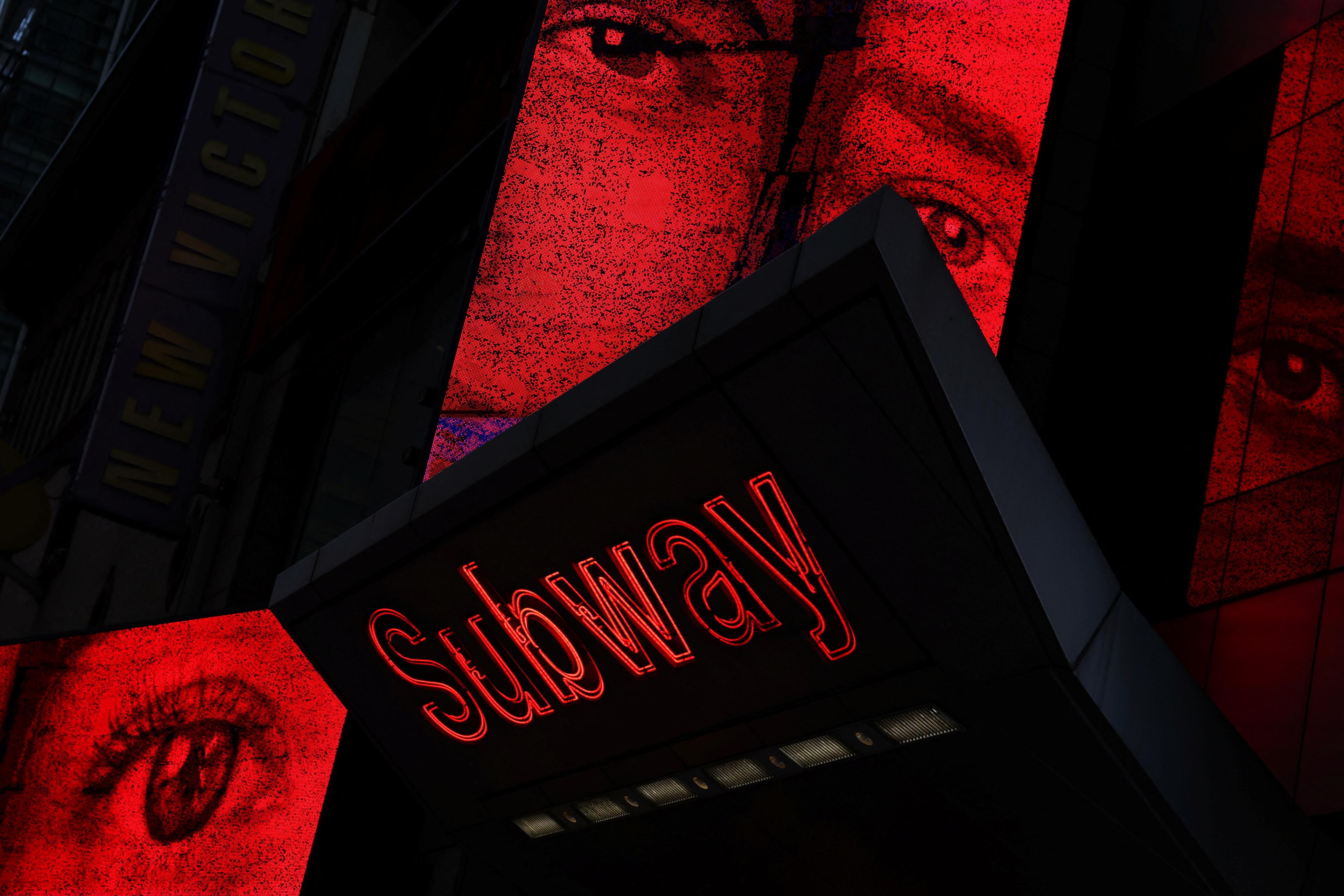

However, avoidance is not always possible, so people who have anxiety often develop behaviours to keep themselves feeling safe when they are unable to avoid a situation completely. These behaviours, known as ‘safety behaviours’, are a subtle kind of avoidance: one enters a feared situation, but does so without really facing the fear. In the above examples, somebody with a fear of heights might always hold on to a handrail when they are on a balcony. People with a snake phobia might go hiking but they’ll wear big boots and carry snake bandages and antivenom even in places where there are no snakes. In the case of social anxiety, someone might wear sunglasses to avoid making eye contact with others, or rehearse a speech over and over again.

The problem with avoidance and safety behaviours is that, although they may reduce anxiety temporarily, they reinforce anxiety in the long term. Anxiety is characterised by exaggerated fears – eg, I will fall off this balcony; I’ll be bitten by a snake; people will think I’m stupid – and safety behaviours prevent someone from learning whether the fears are really true or not. Someone might mistakenly think the safety behaviours themselves are what stopped the feared situation from coming true. The person with social anxiety who rehearses a speech dozens of times might assume that this repetition is what prevented them from making a complete fool of themselves.

Because avoidance and safety behaviours maintain anxiety over the long term, they are key targets in psychotherapy. The part of therapy that deals with them is called exposure therapy because it involves helping people to gradually expose themselves to their feared situation. Facing the situation helps them to learn not to fear the physical sensations of anxiety and to challenge their exaggerated predictions. With regard to safety behaviours, therapists and their clients work together to uncover all the unhelpful things clients do to try to feel less anxious in a feared situation. Then, the client will gradually drop these habits.

Unfortunately, disentangling unhelpful safety behaviours from helpful behaviours is not always as straightforward as it sounds. In many cases, making the distinction can be quite challenging.

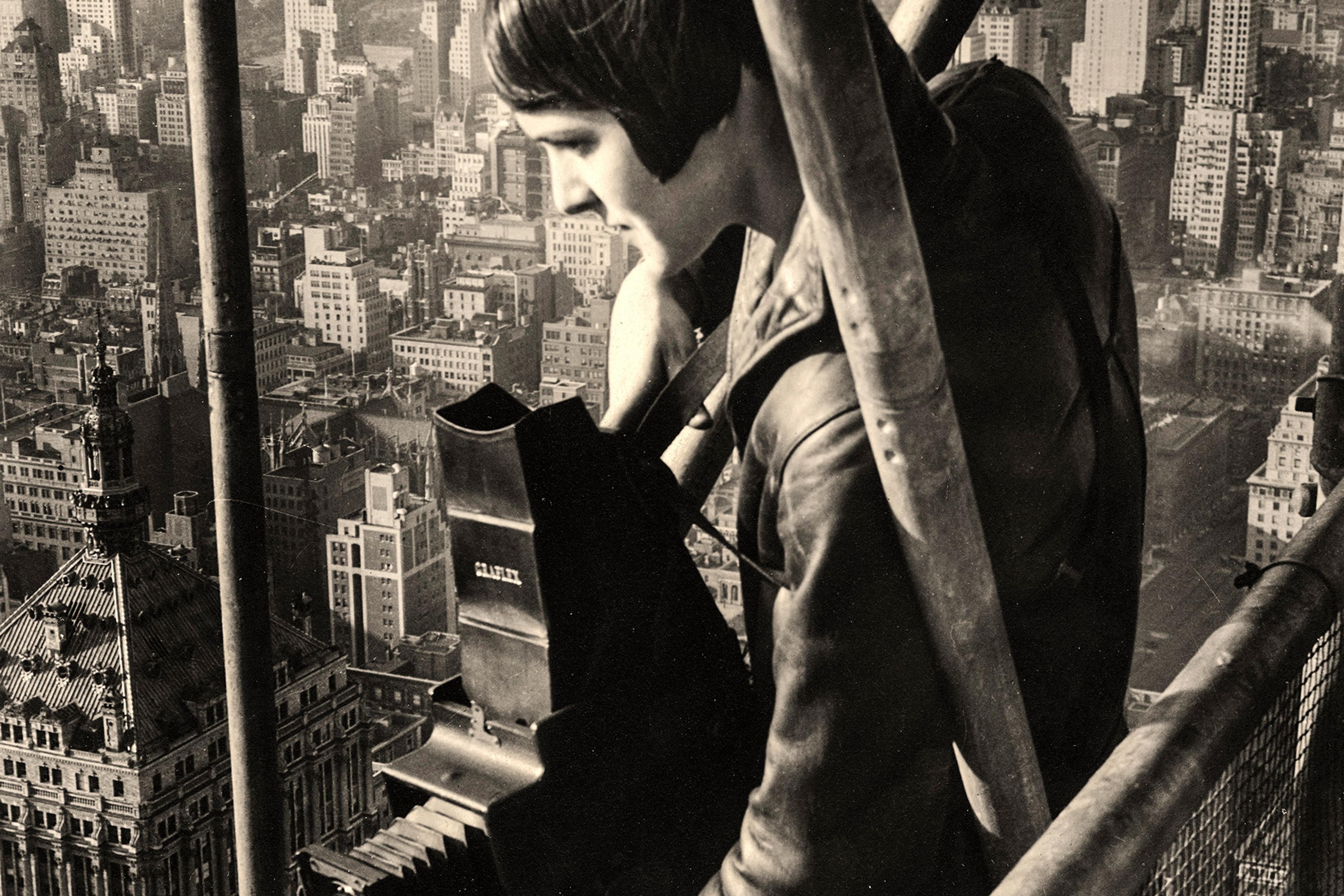

Imagine that you’ve been asked to give a presentation in front of your colleagues and several senior managers. The idea of public speaking elicits some anxiety in you, as it would for most people. You spend many hours over the next week drafting your presentation and rehearsing it repeatedly, staying up late on several nights to ensure you feel sufficiently prepared. Is this intensive preparation a safety behaviour that will reinforce your fear of public speaking? Or is it simply an appropriate way to prepare for an important task?

This issue becomes more complicated when the behaviour in question is intended to prevent physical harm. When is holding on to a handrail while standing on a tall building a maladaptive safety behaviour, and when is it a reasonable precaution? What about carrying pepper spray or phoning a friend while walking alone late at night? When someone feels that their physical safety is on the line, it can be even more challenging to recognise safety behaviours – and more nerve-racking to relinquish them.

It becomes harder still to recognise and disentangle safety behaviours in the context of chronic physical illnesses. Living with a chronic illness can open up a range of new illness-specific fears about things such as re-injury, seizures, hypoglycaemia, or the return or worsening of an illness. Several studies have revealed that anxiety is particularly prevalent among people with chronic illnesses. For example, anxiety disorders are more common in people with epilepsy, diabetes, chronic pain and cancer, compared with the general population.

We recently reviewed the evidence for the negative impact of safety behaviours and anxiety in the context of chronic illness, finding some notable examples. In gastrointestinal illnesses, for example, safety behaviours may include scanning for the nearest bathroom, wearing sanitary items or carrying spare clothes to prevent the feared outcome of soiling oneself or to reduce embarrassment should it occur. In chronic back pain, people have been shown to engage in safety behaviours such as tensing their abdominal muscles before lifting a heavy object to prevent further back injury. In cases where preventative behaviours are not truly necessary, they may ultimately just worsen the anxiety that is layered on top of an already challenging chronic illness.

So, how can one distinguish safety behaviours from sensible precautions? We cannot simply say that a particular behaviour is always ‘good’ or always ‘bad’. For example, routinely using a walking frame might be a safety behaviour for someone with lower back pain, but could be helpful and necessary for someone who is elderly and has a history of falls. A clinical psychologist can help a person to explore their precautionary behaviours in context and to work out what behaviours can be gradually reduced, and how.

To help guide decision-making about whether a particular behaviour is helpful or unhelpful, we recently developed a framework that features a series of questions to ask about the behaviour. This framework was created to help people who are experiencing anxiety in the context of chronic illness, and to assist mental health professionals in working with these individuals. But the questions are also relevant to the behaviours of people with anxiety more generally.

What is the function of the behaviour?

Does the behaviour encourage one to approach feared situations, or does it lead to more avoidance? It may be that a precautionary behaviour allows a person to gradually push themselves in a safe way. For example, if someone is anxious about public speaking, it may be helpful for them to memorise their speech and to ask someone to stand next to them if it enables them to speak at their daughter’s wedding. But insisting on these precautions in everyday settings could reinforce the anxiety and encourage the avoidance of speaking – in which case they are better thought of as counterproductive safety behaviours. For someone with lower back pain, enlisting the help of a physiotherapist may allow them to become more active. However, if the person starts to depend on the presence of the physiotherapist to do any exercise, even though the physio has encouraged them to exercise outside of sessions, that may interfere with progress.

Is the risk realistic?

Considering whether the risk of a negative outcome is realistic can help in deciding whether a precautionary behaviour is appropriate. A person with asthma that is not well managed may face a realistic threat of an asthma attack, and it would be sensible for them to carry their puffer with them. Yet if someone had asthma in childhood and has not experienced symptoms for 20 years, then the risk of an asthma attack is likely much lower and keeping a puffer on hand may be a safety behaviour. Similarly, a person who is afraid to walk home at night without having a companion might be overestimating the risk they face if their route is in a safe, busy and familiar part of town.

Can the risk be mitigated?

In some cases, there is a risk that is out of one’s control. For example, there is little that can be done, apart from routine scans and tests as advised by the doctor, to prevent cancer recurrence. On the other hand, problematic blood sugar levels in diabetes can usually be very effectively managed through behaviours such as good insulin management, diet and exercise. If a person is worried about catching an airborne virus on a plane during a global pandemic, they can reduce this risk by wearing a well-fitted mask. But the same person cannot mitigate the risk of an airplane crash while they are on the plane.

Is the behaviour proportional to the threat?

It is often appropriate in the context of chronic illness to take some precautions. For example, a person with diabetes may take insulin, snacks and blood sugar monitoring equipment when going away for the weekend. However, eating snacks before bed to prevent hypoglycaemia overnight can be excessive when blood sugar levels are already normal, and it could even backfire by raising high blood sugar to harmful levels. Returning to the earlier example of a fear of snakes, if you are bushwalking in an area that is unlikely to have snakes, it may well still be sensible and proportional to the risk to wear boots, but perhaps not to carry antivenom, wear several pairs of socks and bring a stick to hit shrubs along the path.

Does the behaviour allow for engagement in valued activities?

If there is an activity that is really important to you, certain behaviours might be helpful for getting you through. For example, if you have gastrointestinal illnesses, and you are thinking about going on a first date, the stakes might be higher for you than usual. So, in this particular situation, you might decide to book a restaurant with easily accessible bathroom facilities and wear sanitary items, even if these would normally constitute safety behaviours.

If you are struggling with anxiety, considering each of these questions could help make it clearer whether a behaviour is useful or ultimately counterproductive. If you have a chronic physical illness in addition to anxiety, you should work with doctors or mental health professionals to figure out which behaviours are necessary. If it’s unclear whether something is an unhelpful safety behaviour, you might ask your doctor about taking small, safe steps to test out whether it is truly needed or not. It can be challenging, but also very rewarding, to confront anxiety and recognise safety behaviours for what they really are.